The “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” as Post memory: Tonarigumi and Neighborhood Associations

Funo Shuji

Introduction

In the “Translator’s Preface” to “Memory and Silence” (Tanio Akiko, 2003), I wrote. I was impressed by the author’s vivid awareness of the issues. I found the argument to be extremely logical. The concept of post memory particularly struck me. … The scope and depth of this essay are profound.” I then added, “Post memory theory in Japan should explore the ‘memory and silence’ of World War II. This exploration is essential. As a translator, I intend to seriously consider Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Fukushima. I will also think about the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (imagined community) and local communities. I will explore other topics, particularly about architecture.” The editorial team noticed this line. They asked me to write a “Response to the Essays on Post memory and Art.” I shared my interpretation of “Memory and Silence.” To be honest, I was stumped. “I’d like to give it some serious thought” was merely a determination to “take some time and think about it.”

Yet, “Memory and Silence” questions how Japan’s recent past has been suppressed and silenced. This is done by examining the concepts of memory, history, post memory, and silence. The discussion also examines artworks and artistic practices themed around World War II. This directly connects to the debate surrounding today’s “Freedom of Expression?” exhibition at the Nagoya Triennials. Furthermore, “Memory and Silence” sharply points out the concealment of “history.” It highlights the suppression and control of “memory.” The silencing of “memory” is also discussed. These issues are occurring today with matters like the “comfort women” and “forced labor” issues. In particular, since the Abe administration came to power, we have seen a conscious and strategic escalation. This involves the manipulation of “history” (historical revisionism). It also involves the erasure of “memory,” “tacit coercion,” and hidden “censorship.” The Japanese state is presently trying to conceal the history of the 15-year war period. They want to suppress and control the memories that led blindly to World War II. The methods of concealment, suppression, and control remain consistent throughout the 15-year war period. Nonetheless, systems of surveillance and coercion have become more subtle. They have complexly become invisible due to changes in the media environment brought about by advances in information technology. Furthermore, the total war system was supported by familiar community organizations. In this article, I would like to consider the history and memories of neighborhood associations. These associations, and neighborhood groups, supported the total war system of World War II. This system is also known as the Imperial Rule Assistance System. This article takes inspiration from Memory and Silence’s statement. They propose that “post memory serves as a matrix where self and others coexist without merging.” The article is also inspired by the feature “Community Rights: Power to Counter State Power.” This feature appeared in the first issue of Urban Beauty.

1 Memories of World War II: Postmemory and Metamemory

As someone born after the war, I too have no knowledge of World War II. I only have fragmentary information about it through the experiences of my parents and grandparents. Yet, since 1979, I have often encountered memories of World War II while walking throughout Southeast Asia. A farmer I was interviewing in the mountains of Java performed radio calisthenics for me. A becak (rickshaw) driver suddenly burst into song, “Umiyukaba.” Someone also demonstrated to me the kanji characters for “Kinroho” (labor service) and “Kenpeitai” (military police).

When confronted with the memories of history, it’s only natural to learn about history. Recently, I took a reconstruction support trip to Leyte Island, which was severely damaged by Typhoon Yolanda (2015). There, I saw a bronze statue of General MacArthur and his men re-landing on the coast (Figure A). This inevitably reminded me of the final stages of World War II. Naturally, I ended up picking up Shohei Ooka’s “Leyte War.” “Postmemory” refers to a type of memory produced by “reliving” experiences through different media. It involves acquiring and internalizing these memories as one’s own (Tanio Akiko, “Memory and Silence”).

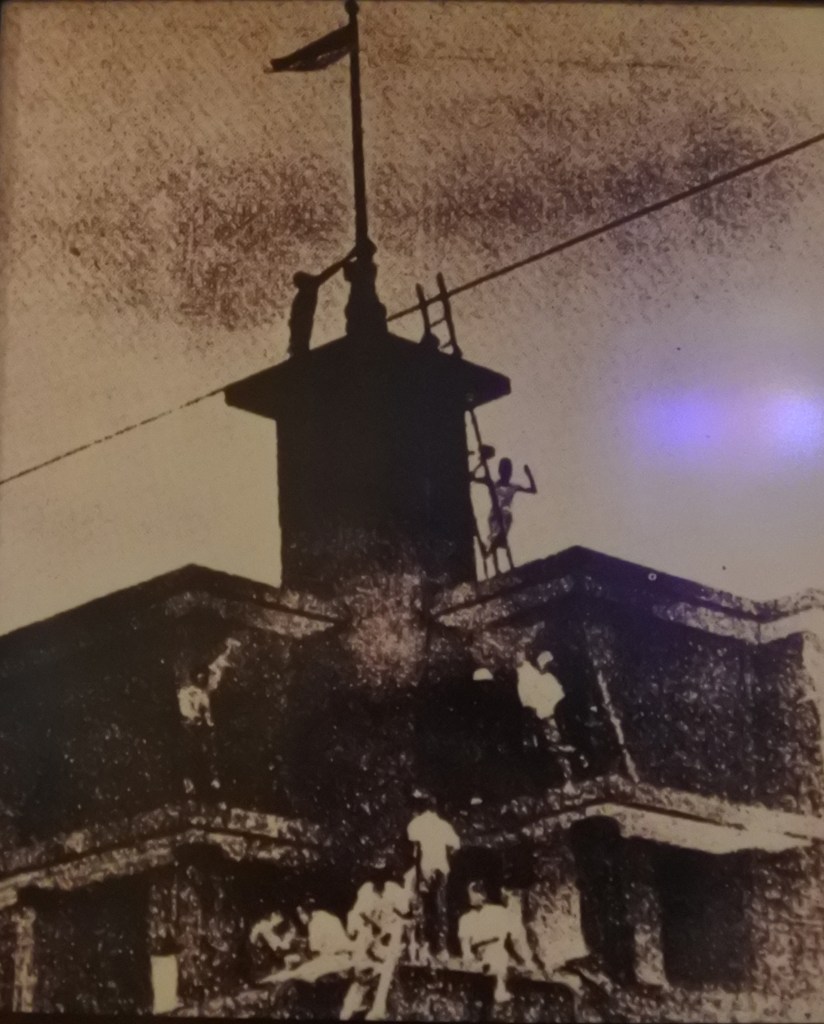

Yamato Hotel

For the past 40 years, I have been conducting research in the kampung (urban village) (see below) of Surabaya, Indonesia. The Battle of the Java Sea occurred on February 26, 1945. It marked the opening of the occupation of Java during the Pacific War. The 48th Division captured Surabaya on March 8, the day before capturing the entire island of Java. Following this, Japanese military rule began. Surabaya became home to the 14th Independent Garrison. This garrison consisted of four independent garrison battalions of the 16th Army responsible for East Java. Memories of World War II are embedded throughout the city. In Surabaya, there is a jalan (street) called Kembang Jepun, which means “Flower of Japan.” This street was Surabaya’s entertainment district. It was lined with izakayas and restaurants. The district was filled with barbers, peddlers, and street prostitutes. Japanese people began migrating to various parts of Southeast Asia in the early Meiji period. During this time, Southeast Asia was known as the “South” or “South Seas.” The first were women known as “karayukisan,” followed by people working in odd jobs (restaurants, seat rentals, barbers, hairdressers, kimono goods, general merchandise, medicine sales, etc.) in their vicinity. It is known that a Japanese community had formed in Surabaya by the end of the Meiji period. My regular hotel, the Majapahit Hotel, formerly the Yamato Hotel, displays a large oil painting in its lobby. It depicts young Javanese men with their arms outstretched on the roof of the hotel. The red and white Indonesian flag is flying there. (Figure B①②) This incident on September 17, 1945, is widely remembered as the event that sparked the War for Independence.

Chronopolitics

Memories of World War II, however, differ between occupying and occupied countries, and between victorious and defeated nations. Carol Gluck (2019) identifies four domains in which “war memories” are created: 1) official domains (national museums, textbooks); 2) popular domains (photography/film/television/IT, popular culture, and memory activists). Activist), 3) personal memory, and 4) metamemory (disputes about memory, chronopolitics). For the United States, “World War II” was a battle of “right against evil.” It began with “Pearl Harbor” (December 8, 1941) and ended with “Hiroshima and Nagasaki” (August 1945). The war known as “World War II” in the United States and Britain began in Western Europe. The conflict started with the Nazi invasion of Poland (September 1, 1939). However, the dates of the outbreak of war differ. In the Soviet Union, the Nazi invasion (June 22, 1941) was the start of the war. It is referred to as the “Great Patriotic War.” In Finland, it is known as the “Continuation War.” In Asia, it is referred to by several names. These include the “Greater East Asia War,” the “15-Year War,” the “Pacific War,” or the “Asia-Pacific War.” In Japan, the period after the Manchurian Incident in 1931 is called the “15-Year War.” The period after 1937 is called the “Second Sino-Japanese War.” After the attack on Pearl Harbor, it is called the “Greater East Asia War” or the “Pacific War.” In China, it is called the “War of Resistance Against Japan.” Since 2015, it has been known as the “World Anti-Fascist War.” Countries that participated in World War II have formed a “common memory” based on their own stories. In other words, the memory of World War II is the story of each nation (state, people).

However, that story, that “common memory,” can change. This is illustrated by the criticism of the “masochistic view of history” by historical revisionists in Japan. In Japan, one story is that the people became victims because of their leaders. They were caught up in a tragic war and are not responsible. However, this story overlooks those who opposed the war. It also neglects the soldiers who died fighting for their country. Carol Gluck (2019) says that there is no such thing as “one story” even within a single country. Furthermore, national stories are not only an issue within a country. They can also be a major problem between nations. These stories affect bilateral “historical awareness.” The issue at stake is the “politics of memory.”

The Holocaust, Auschwitz, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki are global, transnational memories that have influenced the course of human history. However, the narrative of winners and losers (“black and white narratives” (Carol Gluck)) remains unshakable. This is exemplified by postwar Japan’s subservience to the United States (Shirai Satoshi (2013, 2018)). Carol Gluck argues that “World War II” was fought within a complex “global geometry” known as the “heptagon of war.” The “heptagon” includes Germany, the United States, and Britain. It also includes the Soviet Union, China, Japan, and the Western colonies of Southeast Asia.

The politics of war memory (chronopolitics) is created by this “global geometry.” It will not be resolved in a metamemory where nationalisms collide. Today’s increasingly escalating Japan-Korea dispute demonstrates this.

The Matrix

The memory site known as postmemory does not lie at the upper level of national memory. This upper level is formed by Carol Gluck’s four memory domains (1) through (4), i.e., metamemory (chronopolitics). Instead, it is at a deeper level, unrecovered by nationalism. Memory and Silence also cites Bracha Lichtenberg-Ettinger’s “matrix” as another key concept. The “matrix” is “a symbolic space where self and other coexist without merging.” It is a place where “encounters occur between the co-emerging ‘I’ and the unknown ‘I’.” Here, “each neither assimilates nor rejects the other.” Their energy is not fusion. Nor is it repulsion. Instead, it is a continuous readjustment of distance within the bounds of solidarity or proximity. The memory site known as postmemory is such a “matrix,” a “universal memory site” that overcomes the clash of nationalism.

2. The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and Tonarigumi (Neighborhood Associations)

The term “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” was first used publicly on August 1, 1940. Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka (1880–1946) introduced it in a speech. The terms “East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” and “Oriental Co-Prosperity Sphere” appeared in historical documents earlier. However, the term “New East Asian Order” was more commonly used. The “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” concept was initially just a “slogan without substance.” This phrase lacked genuine meaning (Kanishi Kosuke (2012, 2016)). The aim of the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” concept was to exclude Southeast Asia from Germany’s colonial plans. This was before the Tripartite Pact signing between Japan, Germany, and Italy on September 27, 1940. The aim was part of the strategy assuming a German victory at the postwar peace conference.

“Hakko Ichiu” (Unification of the World Under One Roof) and “Liberation of Asia”

The “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” was a concept. It placed the East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (“Japan, Manchuria, and China”) at its core. The idea grew to include the British, French, and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia. Thailand was excluded (“Outline of Imperial Foreign Policy” (September 28, 1945)). It is noteworthy that Matsuoka’s concept envisioned the independence of French Indochina and the Dutch East Indies. Matsuoka Yosuke’s theory of southern independence was a means to an end. It focused on establishing the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” This supported independence and then incorporated them as protectorates. It was not aimed at “liberation” from Western colonial rule. “World War II” was a “war for resources,” a war that put the “Empire” at stake.

The “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” concept was clearly stated. This was in the “Outline of Measures for French Indochina and Thailand” (Principles for Policy toward French Indochina and Thailand). This document was released in January of the following year. It outlined Japan’s role as mediator in the conflict between the Vichy government and the Thai government over French Indochina. Since then, the term has frequently been used as an official term in policy documents. The “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” started to appear widely in newspapers, general interest magazines, and other media. This was alongside slogans such as “Hakko Ichiu” (One World Under One) and “Asia Liberation.”

The “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” was an attempt to build an “imagined community” (B. Anderson), with its content being vague and unfounded. The “Greater East Asia War” occurred under the total war system. This included the National General Mobilization Law (1939) and the Imperial Rule Assistance System. It was administered by the Imperial Rule Assistance Association (1940). Consequently, the harsh reality of the “Occupation of Japan” was imposed.

Tonarigumi as a System of Mutual Surveillance

The “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” was established through neighborhood associations, buraku associations, and neighborhood groups. These were the basic units of society. They supported the total war system of the Greater East Asia War or the Imperial Rule Assistance System. This was done to realize this “imagined community.” All over Japan, neighborhood associations and buraku associations began to emerge. This happened around the time the Sino-Japanese War began (1937). However, they were not positioned as an official neighborhood system until September 1940. This was done with the Minister of Home Affairs’ Directive No. 17 “Regarding the Establishment of Buraku Associations, Neighborhood Associations, etc.” Neighborhood associations were organized in urban areas. Buraku associations existed in villages. Neighborhood groups were established as subordinate organizations. These groups had units of around 10 households. In 1943, the law was amended. It gave authority to mayors of cities, towns, and villages. They could now entrust administrative assistance to the heads of neighborhood associations, buraku associations, and their federations. These associations then became subordinate organizations to the city, town, and village. This Order No. 17, also known as the “Tonarigumi Strengthening Law,” aimed to use the Tonarigumi as a unit to mobilize residents. It provided supplies and distributed controlled items. It also engaged in air defense activities. Additionally, it attempted to control ideology and monitor each other.

Gonin-gumi System

After the war, in 1947, the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (GHQ) banned the Tonarigumi system (Potsdam Ordinance No. 15). At that time, GHQ compiled “The Neighborhood System in Japan: A Preliminary Study of Tonarigumi,” (1948). It looks back on the “historical background of neighborhood organizations” (Chapter 1). The study goes back to the “Goningumi” under the feudal domain system. It further examines the “Goningumi system” established by the Taiho Code (701) and the Yoro Code (718). The study first examines “state control of neighborhood organizations from the 1930s onwards” (Chapter 2). After that, it analyzes “neighborhood organizations in Tokyo” (Chapter 3). It concludes with “the dissolution of neighborhood organizations” (Chapter 4). The GHQ concluded that the Tonarigumi system was a “controlling system.” It supported the total war system and the regime support system. The reason for the ban is that it had become a device for “compulsion and coercion.”

The GHQ’s analysis is truly interesting. As Japanese society gradually freed itself from the ties of blood, new non-blood-related, local-based groups emerged. These groups were neighborhood organizations. The prototypes of these organizations were the “yui” and “ko.” The Goningumi system, stipulated in the Taiho and Yoro Codes, had three functions: 1. mutual aid, 2. collective responsibility, and 3. maintaining order (transmission of orders). The Goningumi system disappeared in the mid-Heian period, but continued to exist in the Muromachi period. It was revived in the late Edo period. The early Edo period also saw its revival as a system for maintaining the feudal domain system. It spread to every corner of the country. The Gonin-gumi of the feudal domain system covered almost all areas of daily life, with the functions of 1. maintaining public order and morals, 2. controlling religion, 3. guaranteeing tax payments, 4. encouraging hard work and savings, 5. mutual aid, and 6. moral education. With the Meiji Restoration, this neighborhood organization was dismantled with the legalization of the family registration system (1872) and the implementation of the city and town system (1888), but it continued to function until the Russo-Japanese War (190 Movements to revive the Gonin Gumi began to appear around the same time (1940-1955), and with the rural economic offensive after the Showa Depression and the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War, the group was incorporated into the wartime system (Yoshihara Naoki (2000)).

As the special feature in the first issue of Toshi Bi shows, there has been much discussion surrounding communities. We must confirm at the very least that communities have two fundamental functions. They protect their members through mutual aid. Furthermore, they control their members through control and coercion.

3 “Greater East Asia Construction Memorial Construction Plan” and “Kampung Improvement Program (KIP)”

Greater East Asia Architectural Style and the New Architectural System

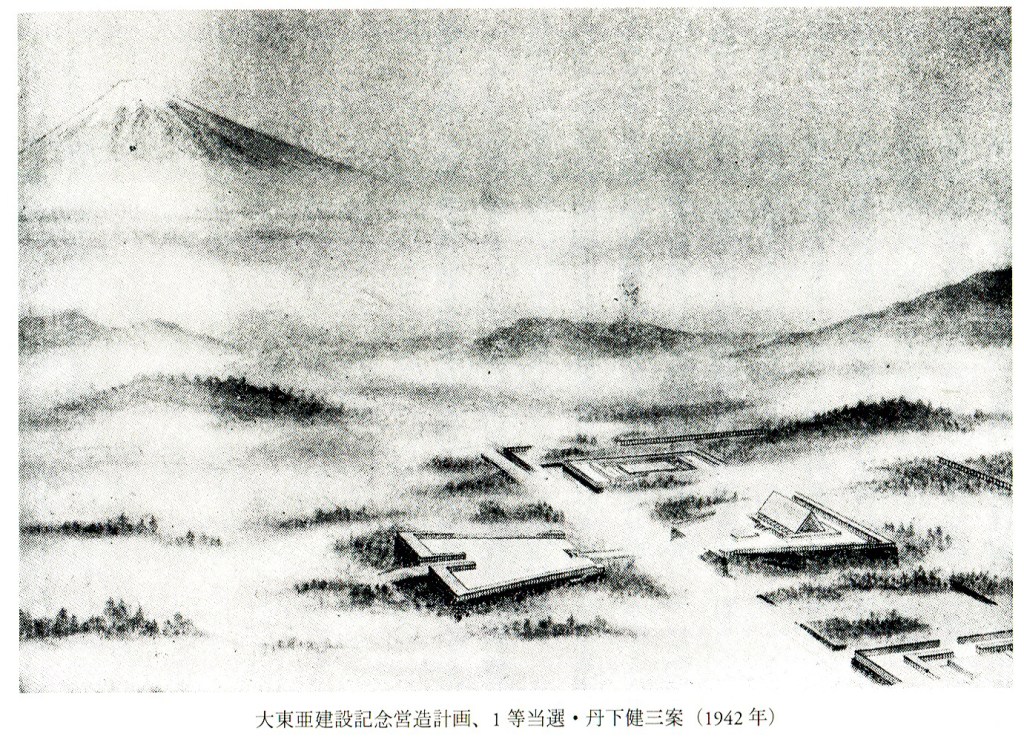

Regarding “World War II and Architecture,” essays have discussed architecture and architects during the 15-year war period to some extent. These include “Architecture and Culture in the 1930s” (Gendai Kikakushitsu), edited by the Contemporary Architecture Research Group (1981). Some other essays include “Architecture as a Movement: Notes on Showa Architecture” (Kenchiku Bunka, November 1975). Another is “The State and Postmodernism” (Kenchiku Bunka, April 1984). Lastly, “Shuji Nuno’s Architectural Essays III: State, Style, and Technology—Architecture in the Showa Era” (Shokokusha, 1998) is also noted. The primary issue often discussed is the “Imperial Crown (Annexation) Style” (Shimoda Kikutaro). The “Greater East Asia Architectural Style” is also frequently examined. These styles are considered forms of Japanese fascism. Kenzo Tange’s “Greater East Asia Construction Memorial Construction Plan” (1942) (Figure C) is symbolically considered.

The “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” concept would have carried no real weight. It would have remained merely a concept on paper. Discussions of this “Greater East Asia Architectural Style” concept would likely have been hollow. The “Greater East Asia War” was destructive. Yet, it was fought in the name of building the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” The “Association for Promoting a New Architecture” was formed in September 1940. The architectural world as a whole was caught up in the Imperial Rule Assistance System. Countless architects and engineers served in the war, and some were “recruited to the South” for cultural projects. However, while there are numerous “recollections” from writers and intellectuals, the reality of this situation remains largely unknown among architects.

The Sea of Kampung

The Western colonies in Southeast Asia continued to experience turmoil. This included the wars of independence. It also included the Vietnam War under the Cold War structure. Surabaya, along with Singapore and Manila, is one of the few Southeast Asian cities to have suffered complete destruction. Indonesia experienced turmoil after Japan’s defeat in the war. The country then faced the War of Independence. This was followed by the September 30th Incident (1965). In addition, there was explosive population growth. Major cities like Jakarta and Surabaya were filled with kampungs (urban villages). These were formed by large influxes of people from rural areas. The urban infrastructure remained unchanged from the 1930s. The living conditions in these kampungs, lacking water, sewage, or electricity, deteriorated.

In response, kampung residents began to take the initiative to improve their living environment. Local governments started to support these efforts. This was called the Kampung Improvement Program (KIP).

The KIP essentially required local governments to offer minimal improvements to the living environment. These improvements included installing water and sewage systems, paving sidewalks, and installing public toilets. Housing construction was the responsibility of the residents. Cleaning, garbage collection, greening, and maintenance were handled by the kampung’s voluntary mutual aid activities. Public housing provision was ineffective. KIP was launched at a local government level. It was recognized as the most successful example of addressing the living needs of the urban poor. It attracted the attention of the World Bank and the United Nations, and was eventually elevated to national policy.

Squatter Area

I first walked through a kampung in Jakarta in early 1979. The following year, KIP won the first Aga Khan Award. This award recognizes outstanding architecture in the Islamic world. At the beginning of “The World of the Kampung” (Nuno Shuji, 1991), I mentioned an important detail. A renowned Japanese architect was on the selection committee. KIP was ultimately selected unanimously. However, the architect dissented. He has repeatedly mentioned this incident in several places.

“Squatter means an illegally occupied area. It refers to villages and towns that are formed when refugees or unemployed people come to the city. They collectively occupy hills or fields and build houses there without permission, regardless of who the land belongs to. At first, there is no electricity or running water. Gradually, improvements occur. Roads are constructed. Open channels are created to drain dirty water. Water and electricity are brought in. Facilities that serve as community centers for the whole area are also built. I gave several examples of villages formed in this way. I wanted an award for them as well. Since it’s called an architecture award, I argued that it would be problematic. They should have a certain level of culture.”

The architect who said that kampung communities lack culture is none other than Tange Kenzo. He won first prize in the “Greater East Asia Construction Memorial Building Project” competition.

4. Developmental Dictatorship and RW (El Way) and RT (El Teh)

Kampung and Compound

“Kampung” means “village” in Malay (Indonesia, Malaysia). The “village” in a city, town, or village is called “desa.” In contrast, “kampung” is the more commonly used term for “village.” “Kampunggan” has a connotation of “countryside.” Interestingly, the term “kampung” is also used to refer to residential areas in large cities. It translates to “urban village” in English. According to C. Geertz (1965), kampung is the urban reintegration of desas, which retain a strong “communal” character.

Gotong royong (mutual aid) is considered the highest value of the Javanese. It is also seen as the national slogan of Indonesia. Gotong royong supports the lives of kampung residents. The traditional Javanese concept of rukun, meaning “harmony, unity,” is also highly valued. Cities in Indonesia have kelurahan as their current administrative unit. Its sub-units include rukun warga (RW) and rukun tetangga (RT). Tatanga means “neighbor” and warga means “resident.”

Interestingly, there is a theory that the word kampung is the origin of the English word compound (Shiino Wakana, “‘Compound’ and ‘Kampung’: A Historical Study of Anthropological Terminology Related to Residences,” Annual Report of Social Anthropology, Vol. 26, 2000). In areas colonized by the British Empire, villages were generally called compounds. It is suggestive that “enclosed areas” such as concentration camps were also called compounds.

Tonarigumi, Aza, Joukai

The Japanese neighborhood system was introduced to Java under Japanese military rule. This included “Tonarigumi” (neighborhood associations) and “Joukai” (town associations). This occurred toward the end of the Pacific War. On January 11, 1944, the All-Java Provincial Governors’ Conference announced the simultaneous establishment of neighborhood organizations across the island. The “Outline of the Neighborhood System Organization” was subsequently issued. The Japanese terms “tonarigumi” (neighborhood association), “aza” (character), and “joukai” (regular association) appeared directly. This is a near-copy of the Japanese neighborhood system. Its purpose was to “serve as an organization and practical unit for homeland defense, economic control, etc., and to infiltrate military rule as a subordinate organization of local government. It also aimed for the accomplishment of mutual aid and other common tasks among residents. This was based on the ancient Javanese spirit of neighborhood mutual aid (gotong royong). Additionally, all the households within the Dessa would be divided into neighborhood associations of roughly 10 to 20 households. Each neighborhood association would have a leader, who would be selected with the highest priority on practical ability. The neighborhood association would hold regular meetings at least once a month. Furthermore, each village (kampung) would establish a neighborhood association. It would hold regular meetings at least once a month. The neighborhood association would be composed of the village leader, neighborhood association leaders, and other knowledgeable people within the village.” .

The origin of today’s RT is the Tonarigumi organization. It spread across the entire island of Java in just over a year at the end of the Pacific War. But why has the Tonarigumi system survived to this day? Has the current RT continued to exist as the same as it did under the wartime system? On the other hand, was Japan’s Tonarigumi-chonai-kai system actually dismantled during the postwar reforms? How are the chonai-kai that continued to exist after the war different from those under the wartime system?

The history of Tonarigumi in Indonesia is as follows (Sullivan, John (1992)).

With Japan’s unconditional surrender, Indonesia began fighting a war of independence. The RT and the aza system were formed in the Rukun Kampung RK (Rukun K). The RT and RK continued to exist as neighborhood organizations. They performed roles such as collecting taxes and registering residents. They also checked immigration status, compiled population and economic statistics, communicated government orders, and provided social welfare services. As social organizations, the RT and RK received government assistance and protection. They subsidized the government, but they did so informally. In 1960, the Local Administration Law regarding the RT/RW came into effect. This law designated the RT/RK as a residents’ organization. It remained independent of the government and political parties. Efforts to incorporate the RT/RK into government institutions began to take shape only after the “new regime” was established. This occurred following the coup d’état of September 30, 1965.

September 30 Incident

After assuming the presidency, Suharto shifted Indonesia’s foreign policy to a pro-American, pro-Malaysian, and anti-communist stance. He rejoined Indonesia in the United Nations and established the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1967, with its secretariat based in Jakarta and pursuing a cooperative policy with neighboring countries. Meanwhile, he imposed an authoritarian dictatorship on the domestic front. “Pancasila democracy,” with its mottos of mushawara (discussion) and mufakat (unanimity), was linked to an ingenious system that supported Suharto’s developmental dictatorship. While touting democracy, the Suharto regime was dominated by Golkar (Golongan Karya). Apart from the government-supported pro-government group Golongan Karya (Professional Group), only two opposition parties (the Indonesian Democratic Party and the Development Unity Party) were permitted. Driven by the “memory” of the September 30th massacre, the military suppressed independence movements in East Timor, Aceh, and other regions, and abducted, converted, tortured, and massacred democracy activists. The regime also thoroughly suppressed media outlets critical of the regime.

Under Suharto’s “new regime,” the RT/RK gradually lost its independence. However, the enactment of Village Government Law 5 in 1979 marked a turning point in the system. A major change was the introduction of a new neighborhood unit called rukun waruga (RW), which brought together several RTs. In 1983, the Minister of Home Affairs enacted a decision throughout Indonesia. This set new regulations for RT/RW. No. 7/1983) (Regulation No. 7) was enacted. RT/RW were fully incorporated as institutions of the state system.

As mentioned above, Indonesia’s RW/RT originated as a forcible introduction during the Japanese occupation. However, they continued to exist as autonomous, self-sufficient mutual aid organizations even after independence. This continued because the traditions of desa and the mutual aid mechanisms of neighborhood associations resonated with each other. However, as the developmental dictatorship was established, RW/RT were once again incorporated into the state system. The characteristics of kampungs include mutual aid activities that support daily life. During elections, they transform into massive vote-gathering machines. These traits are the very embodiment of dual community regulation. This includes internal regulation of mutual aid and external internal control.

By maintaining a strong political base, Suharto remained in office for six terms, a long 30-year run. During this time, he succeeded in promoting industrialization and bringing about economic development. However, as his rule continued, corruption gradually began to be seen as a problem. The collapse of the Suharto regime was precipitated by the Asian currency crisis of 1997-98. In March 1998, Suharto was re-elected president for the seventh time. Dissatisfaction with his administration reached a peak. As anti-government demonstrations spread from Jakarta to regional cities, he was forced to resign as president in May.

This is how the author arrived at the comparison. They examined the process by which neighborhood associations and neighborhood groups were incorporated into a wartime system. The author also compared their collapse to the rise and collapse of developmental dictatorship.

Conclusion

I have long sympathized with Yamamoto Riken. His work “Spaces of Power/Power of Space: Designing the Gap Between the Individual and the State” (2010) resonates with me. I admire “A Model of Regional Social Rights” (2015). I am also impressed by his proposal for “community rights” (the first issue of Urban Beauty). He wrote “The Naked Architect: A Theory of Town Architects” (2000). He has also conducted a fair amount of experimental endeavors. These include founding the Kyoto CDL (Community Design League) and the Omi Tamakijin (Community Architect) Regional Revitalization Studies Institute. I have collaborated with Riken on policy planning. This work was for the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism’s “Community Architect System.” The fundamental question being posed is what “region” and “community” are in Japan. In other words, we need to identify the collective entity. This entity should establish “regional social rights” and “community rights” between the state and the individual. We must also determine where we can find the potential. After the war, neighborhood associations were dismantled by GHQ, but were revived when Potsdam Decree No. 15 expired with the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty. I won’t delve into the subsequent debate over Japanese neighborhood associations. Some say they were “discontinued” before and after the war. Others argue their fundamental role continued. However, what is generally pointed out is the hollowing out of neighborhood associations and the decline of local communities. Since the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, expectations have been high for voluntary associations to play a role. These expectations were further elevated with the enactment of the Act to Promote Specified Nonprofit Activities (March 1998). In any case, expectations are high for various attempts to reconstruct “communities” (local republics, etc.) that are not relegated to “subordinate organizations” of the “state power” that imposes “nationalism” and “xenophobia.”

I was unable to devote space to Surabaya’s kampungs and KIPs. However, they are a truly vibrant part of urban development. The mayor is Tri Rismaharini (born 1961; in office from 2010 to 2015, 2016 to present) (Figure D). Tri Rismaharini, nicknamed Risma, graduated from the Faculty of Architecture at the Institute of Technology Surabaya. He is a student of J. Silas (1936-), with whom I have collaborated for many years. Since taking office in September 2010, Mayor Risma has implemented proactive policies. His vision is to realize a community-based economy and create a vibrant city. He aims for it to be environmentally friendly, a clean and green kampung. Interestingly, he has promoted kampungs’ independent initiatives. He has done this by holding various seminars in all 31 kecamatan (districts). He also assigns motivated citizens to each kampung as environmental facilitators. Additionally, he holds environmental contests as part of the program. In its list of the “World’s 50 Greatest Leaders,” Fortune magazine (March 2015) ranked Mayor Lisma 24th. They cited him as “a mayor who speaks honestly about the issues he faces.” He also inspires his citizens.

I believe that building networks based on the exchange of experiences across borders will offer great help. This will aid in establishing “regional communities” that are not relegated to national systems.

References

Hiroaki Adachi (2002), Prewar Japan and Southeast Asia: From the Perspective of Resource Acquisition, Yoshikawa Kobunkan

Hiroaki Adachi (2012), Economic Vision of the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere”: Intramural Industries and the Greater East Asia Construction Council, Yoshikawa Kobunkan

B. Anderson (1987), Imagined Communities: The Origins and Trends of Nationalism, translated by Takashi Shiraishi and Saya Shiraishi, Libro

Hisao Otsuka (1955), Fundamental Theory of Community

Kousuke Kasai (2012), The Expansion and Collapse of Imperial Japan: Historical Developments toward the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere,” Hosei University Press

Kousuke Kasai (2016), The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere Imperial Japan’s Southern Experience, Kodansha Sensho Metier

Aiko Kurasawa (2012), The War for Resources: The Flow of People and Goods in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, Iwanami Shoten

Carol Gluck (2019), War Memories: Special Lecture at Columbia University – Dialogue with Students, Kodansha Gendai Shinsho

Satoshi Shirai (2013), Permanent Defeat: The Core of Postwar Japan, Ohta Publishing

Satoshi Shirai (2018), National Polity: The Chrysanthemum and the Stars and Stripes, Shueisha

Naoki Yoshihara (2000), Local Residents’ Organizations in Asia, Ochanomizu Shobo

Shuji Nuno (1991), The World of the Kampung, Parco Publishing

Geertz, Clifford (1965), “The Social History of an Indonesian Town,” M.I.T. Press

Sullivan, John (1992), “Local Government and Community in Java: An Urban Case Study,” Oxford University Press

Leave a comment