2024 Pritzker Prize Commemorative Lecture

Illinois Institute of Technology Crown Hall, May 16, 2024

A Theory of Community Based on the Concept of Threshold

Riken Yamamoto

I believe that the work of architecture is extremely important for changing the world.

First, I would like to talk about the “threshold.” This is a very common word, but it refers to a very important space that connects the public and private spheres.

I learned a lot from the German philosopher Hannah Arendt. A German-Jew, Arendt fled the Nazis to the United States and became a professor at the University of Chicago in 1963, conducting much of her research here in Chicago. While specializing in political philosophy, she was also an exceptional translator of architectural space and philosophy.

I would like to start by introducing a quote from Arendt’s *The Human Condition* (1958). This is very difficult to understand, but I believe that as a philosopher, she thought about the “threshold” in spatial terms.

What is important for a city is not the interior of this [private] sphere, which remains hidden and has no public significance, but its external manifestation. It appears in the urban realm through the boundaries between houses. Law originally referred to these boundaries. And in ancient times, it remained a single space—a kind of no-man’s land between the private and the public, guarding and protecting both realms while simultaneously separating them(The Human Condition, translated by Hayao Shimizu, Chikuma Gakugei Bunko, p. 92).

This passage is about the relationship between ancient Greek townscapes and the houses that stood there. Townscapes consist of rows of houses facing the street. Arendt’s “exterior appearance” refers to the gates, and she argues that the way a house appears to the street is more important than its interior. Houses shared walls and were in contact with each other. Furthermore, the house was not an independent concept, but rather a relation to the city (polis).

Arendt continues, “The law of the city-state is, quite literally, a wall” (The Human Condition, p. 93). Let’s take a look at the ancient Greek cities (polis) that Arendt quotes. Many polis were artificial colonies built in entirely new locations and were walled spaces. The determination of ownership through living on allocated land was the origin of the concept of law.

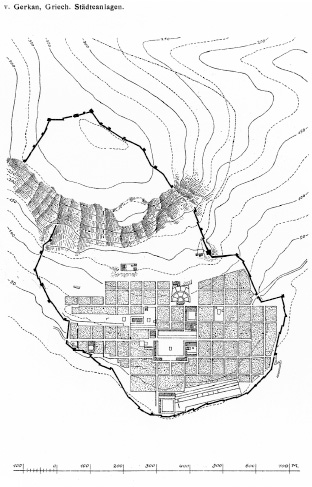

For example, the ancient city of Priene, overlooking the Aegean Sea, had a central square called the agora. Despite the sloping land, the layout of the polis (Figure 1) shows a perfect grid plan. Priene was no exception; it was a colonial city. It was important that the city existed before settlers gathered to live and begin their activities, and to maintain population control in order to protect the political system. For this reason, urban planners created a homogeneous, clearly defined grid plan, assigning equal value to neighbors.

Figure 1: Plan of Priene (Source: Plan of Priene, in Griechische Stadeanlagen Wellcome M0009550.jpg” is licensed under CC BY 4.0.)

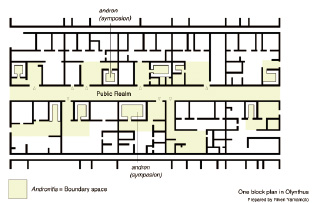

Let’s take a closer look at the grid plan. Looking at the layout of houses in the ancient city of Olynthus (Figure 2), we can see that all the houses are equally rectangular, and the roads leading from the houses connect to the agora.

Figure 2: Plan of Olynthus (created by Yamamoto Riken)

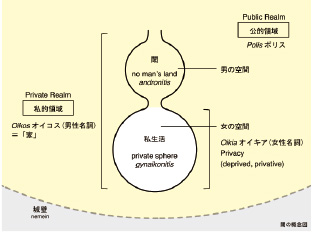

Ancient Greek homes were strictly divided into a men’s area (andronitis) and a women’s area (gynaekonitis). At the center of the men’s area was the andron, a room for eating, drinking, and discussing (feasting). Women did not participate in feasts, and only men were official citizens of the polis. When men invited other citizens into their homes for feasts, the area connected from the gate to the andron was called Andronitis. Conversely, Gynaikonites, where women performed housework, was isolated as the most private place. This is the origin of the concept of “privacy” as used today, and Arendt explains that the word “private” includes the concept of “lack.” Gynaikonites is “a state of being deprived of something.” Andronitis is located between the public and private spheres, an ambiguous place that belongs to neither. This is what Arendt calls “no man’s land” and “threshold.” Andronitis = no man’s land = limbo is contained within the house and is a private sphere. In other words, there is a public sphere known as the “threshold” within the house(Figure 3).

Figure 3: Conceptual diagram of “threshold” (created by Yamamoto Riken)

This structure, in which architectural devices known as “thresholds” connect or separate public and private spheres, is not unique to ancient Greece. I have previously surveyed settlements around the world and seen many very similar spaces.

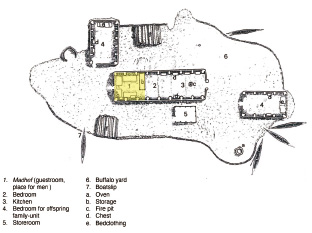

Take, for example, the village of Tjibaish in southern Iraq (Figure 4). This is a waterside area bordering the Euphrates River, and people travel by boat. They build an island for their family to live on, with other houses located far away across the water. Looking at the plan of the island (Figure 5), we can see that connected to the dock is an area called the “madif,” a men’s space for welcoming visitors. When we disembarked, we were treated to coffee around the hearth set up in the madiff. Only men visit the madiff; women do not participate in such receptions. The madiff is the only public area within the house, and is very similar to the andron of an ancient Greek home.

Figure 4: The village of Tibaish, Iraq © Hara Hiroshi Laboratory, Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo

Figure 5: Plan of a house in Tibaish, Iraq. The yellow area is Madif (Source: “Housing Set Theory II”)

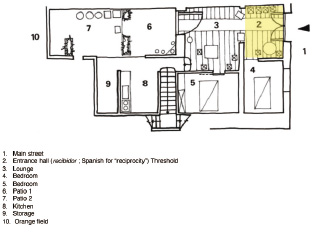

In Petres, Spain, on the border with France, a ruined Romanesque church stands on the hillside, and a village lies below the road leading from it (Figure 6, 7). Arendt states that the external appearance, or facade, is extremely important for public space, and the houses in Petres have beautiful facades, and the room leading to the entrance is a beautifully finished foyer-like space. This area is called a “recibidor,” which apparently means “a place of mutual interaction” in Spanish. Here too, a space resembling a “limbo” exists (Figure 8).

Figure 6: Bird’s-eye view of the Petres settlement © Hara Hiroshi Laboratory, Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo

Figure 7: Houses facing Petres Street © Hara Hiroshi Laboratory, Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo

Figure 8: Plan of Petres’s house. The yellow part is the Recibidor (Source: “Housing Set Theory II”)

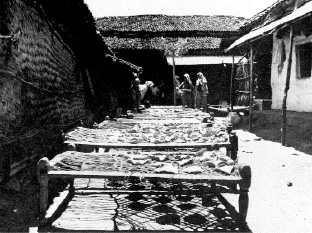

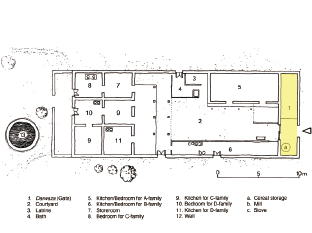

In Junapani, central India, I saw an extremely large house (Figure 9, 10). The home of Patol, the village chief with three wives, has a large courtyard. The space at the entrance is called a “darwaza” in Hindi, and is used to entertain visitors. Beyond the darwaza is a courtyard called a “dueli,” and at the very back is the “andarat,” with a hearth. Darwaza refers to the men’s area, and andarat refers to the women’s area. The Indian family structure is known as the “joint family,” and as a patriarch, his multiple wives, and married children each have their own andarats, the household gradually expands in size. Yet the darwaza, the symbol of the male patriarch, remains the same.

Figure 9: Courtyard of a Junapani residence © Hara Hiroshi Laboratory, Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo

Figure 10: Plan of a Junapani house. The yellow area is the Darwaza (Source: “Theory of Dwelling Sets II”)

Though their forms may differ, the recibidor in Spain, the madiff in Iraq, and the darwaza in India are all “limbs.” And so, various settlements around the world share similar structures across time and space. The public sphere of the polis or settlement is a large community sphere, while the home within that community is a private sphere—a small community. The liminal space protects and safeguards the two, while simultaneously separating them. Modern architects often think of the architectural space of the home as an “internal issue,” but the home also has a liminal space that opens to the public sphere. The issue of the home is also an issue of the outside, of its relationship with the city.

Finally, I’d like to borrow Arendt’s words once again.

The world existed before the individual appeared within it, and it continues to survive after he or she leaves. Human life and death presuppose such a world. (The Human Condition, p. 152)

I believe that architecture exists before people exist and will continue to exist after they die. This is why architecture is so important to people’s lives. Even after someone passes away, their home or city continues to preserve their memory. This is because homes and cities continue to exist for a much longer period than a human lifespan. Following Arendt’s belief, I want to create such architecture. Thank you very much.

Panel Discussion

Riken Yamamoto

Manuela Lucá-Dazio

Diébédo Francis Kéré

Anne Lacaton

Jean-Philippe Vassal

Manuela Luca-Dazio: Thank you, Riken, for sharing your thoughts on architecture, your experiences in the village, and your inspiring talk. Now, let’s give a warm round of applause to our other speakers: Anne Lacaton, Philippe Vassal, and Francis Kéré, the 2021 Pritzker Prize Laureates. I’d also like to extend my gratitude to Hiroshi Watanabe, who is here today and has translated Riken’s work. And I’d also like to thank all of you for participating. I’m looking forward to hearing about the lives of the architects here today, their experiences as young architects, their successes and failures.

First, I’d like to talk about “community,” which you mentioned earlier. I believe community is a fundamental element in your intellectual approach and architectural practice. You have all shown how architecture can reconstruct the boundaries between the public and private spheres. So, I’d like to start by asking about your personal memories of community, your earliest memories. Please tell us how this relates to your current work.

Anne Lacaton: When we began our architectural practice as Lacaton & Vassal, we strongly believed that, as architects, we should create the best possible spaces for people to build communities and develop their lives. Spatial generosity was very important to us, because generous space creates the conditions for freedom to do things. In other words, architecture does not create community; rather, it provides the conditions for a community to exist, for people to meet and work together.

Community begins with the most basic unit: the family. The home is the first space where a community emerges. As Riken mentioned in his lecture, family space is both a private and public sphere, a place to invite others. To achieve this, I think it is important to create surplus space—free spaces that are not dedicated to a specific function. It is these spaces that enable families and individuals to create their own communities.

Francis Kéré: I am very happy to be here today. Looking back, when I was a child, my family would gather in the evenings and my mother and grandparents would tell us all kinds of stories. I recall a strong sense of unity and energy when we all sat together outside our homes. Since I began studying architecture, I’ve always wondered, “How can I create a space where community life can take place in a comfortable environment?” I grew up in a rural village in Burkina Faso. Small animals roamed the area, and the strong Sahara winds sometimes disrupted daily life.

Neighbors would pass by our houses, hear our stories and songs, and join in. I’ve always wanted to create a place where people can share that kind of joy. In the village that Riken showed me, open spaces were created rather than enclosed, and it was truly beautiful. I believe it’s the kind of space or place where you can invite passersby into your home and enjoy it.

This is how I remember and think about community life. And it continues to influence my architecture today.

Philip Vassal: I first met Riken about 10 years ago in Yokohama, when we held a workshop on the theme of “Creative Neighborhood.” A key part of our discussion then was thinking about how we can create this within cities.

Cities can be challenging at times. But cities also provide a place where various social relationships emerge, where people meet, and where they can invite others while still having their own private spaces. Particularly in densely populated cities, it’s important for small communities to have their own space and create places where even small groups can interact. Sometimes people find themselves alone in these spaces. And these small communities build up to form a city. In other words, there’s a structure that grows from the inside out, not from the outside in. Living means feeling happy, feeling comfortable in a place, and having fun. We need to value the people who live there, the social relationships they build there, and the quality of the space that allows for this.

Luca Dasio: From what you’ve all said, it seems that the concepts of “threshold” and common space also have an aspect of generosity. Irish architects Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, winners of the 2020 Pritzker Prize, chose the theme “FREESPACE” when they served as general directors of the 2018 Venice Biennale. Their curation aimed to create free spaces, places where people unconsciously stay.

Riken, you’ve introduced us to the “thresholds” and common spaces you’ve seen on your travels around the world. So what is your first memory of community?

Yamamoto: I grew up in the suburbs of Yokohama. My mother was a pharmacist and ran a pharmacy at home. My family life was closely connected to the pharmacy. Because the pharmacy was also a place of business, it was always open to the outside world. As a pharmacist, my mother worked and lived with strong ties to the outside world. The pharmacy was an important facility for the community. My father passed away when I was five years old, so my mother was also the head of the family. Therefore, she had two roles. This is my first memory of community.

She was like a mother to me, and sometimes she enjoyed living with our family and outside the home as a pharmacist. I sometimes found this frustrating. There’s a contradiction between family life and community life. We want to respect our family’s privacy, but sometimes it’s necessary to participate in the community outside.

However, many homes today have no connection to the outside world, and the public and private spheres are completely separated. Especially in densely populated cities like Chicago, New York, and Tokyo, family life is isolated from the outside world. Modern homes present a contradiction. This is because it’s extremely difficult for a family to live solely within the home, yet this separation from the outside world makes it difficult to create a community.

Luca Dasio: Thank you. Next, I’d like to ask you about your career as an architect. Tell me about a moment of great disappointment or failure—a moment when you thought, “This isn’t working.” On the other hand, I’d also like to hear about a positive turning point when you realized, “This architectural method will work.”

Vassal: I feel very sad and disappointed whenever a building is demolished. From a sustainability and ecological perspective, it’s very important to utilize what already exists. The fact that a building has existed for a long time means that, even if it’s not in the best condition, it has a history, and the walls retain traces of the people who once lived there. Existing buildings can be added to, reshaped, and layered on without being demolished. That’s why it’s so sad when they are eventually demolished; it’s such a shame that the memories of the people who lived there are erased.

Lacaton: I completely agree. For more than 20 years, we’ve been designing with the philosophy of “Never demolish, never remove or replace, always add, transform, and reuse!” However, I feel that we have failed in convincing the public that preserving, renovating, and revitalizing all buildings is a better solution. We can no longer accept a long-winded debate; we need to move faster. After all, in France, 200,000 homes have been demolished over the past 24 years, and the same number have not been rebuilt. The housing shortage has not been solved, and I believe similar problems exist in other countries. This is a failure for us.

Luca Dazio: But you’ve had plenty of successes as well as failures, haven’t you?

Lacaton: Yes, as an architect, I try every day to avoid failure. And it’s important to always stay positive. We’ve believed from the beginning that things would work out. It’s important to always remain positive and optimistic.

Kéré: After studying architecture in Germany, my first design project was the construction of the Gando Primary School in Burkina Faso. With the help of many people, we were able to raise funds for the construction and were fortunate to be able to work with the community to create the building. We used materials that the local people knew. The problem with this material, clay, was that it was vulnerable to rain. Then, about one meter into the construction, heavy rain fell. It happened at night, and it was a huge surprise. Just when we thought all our efforts had been in vain, someone came running to take a look and tell us the building was fine. The design and construction of the Gando Primary School was like a miracle, thanks to the local materials and the community. Since then, I’ve received many requests to build similar buildings. To do so requires funding and a lot of resources.

I didn’t initially intend to pursue a career as a designer in Europe. I wanted to return to my hometown once I had gained some money and knowledge, and work face-to-face with the local people. I returned to Germany, where I was based, to respond to a request from a village in Burkina Faso. As a result, I no longer had time to be in the village. One day, when I returned to the village, the women said to me, “He no longer has time to build with us.” I realized that by fighting alone for the local community, I was actually distancing myself from it. So I got the people I was working with to become more actively involved, so that they could continue the project while I was working in Europe. This method worked well, and it’s still ongoing today.

However, I then faced another problem. In one project I was working on in Germany, the city had provided us with farmland and we had obtained building permits, but suddenly, some smart people showed up and said, “That’s enough. Architects are playing around too much. We want something serious.” As a result, the ideas I had created with the community were rejected, and what should have been a desire for innovation ended up being a desire to maintain the status quo. This is a major challenge for me.

But I still believe in what I’m doing, and I haven’t given up. I see it as a never-ending cycle of failure, struggle, and opportunity.

Luca Dazio: What about you, Riken? Tell us about your disappointments and successes.

Yamamoto: There have been many disappointments (laughs). We’ve had a hard time dealing with local governments, especially when building public buildings. Many local governments want to create apartment complexes where family space and shared space are completely separated. The most important thing for them is maintaining privacy. However, in modern Japan, the average family size is 1.9 people, or less than two. There are also a lot of single-person households. The number of elderly households is also increasing. So I proposed a way to create community through housing, but it led to a struggle with the local government. It’s very difficult to create a community while maintaining privacy.

Our first attempt was in 1991. The project was the “Kumamoto Prefectural Hotakubo Daiichi Housing Complex,” completed in 2013. The housing complex’s 110 units are arranged around a large courtyard, completely isolated from the outside world. The courtyard is a common space created for the residents. However, the project received a lot of criticism from many architectural professionals and journalists, with some saying that the units are too close to the outside and that it’s impossible to live in a place with such little privacy. However, many residents have since come to spend their time as they please around the courtyard, and I believe the plan was a success.

Kumamoto Prefectural Hotakubo Daiichi Housing Complex. View of the apartments from the courtyard. © Isao Aihara

In South Korea, in 2010, I designed the “Pangyo Housing” housing complex. This housing complex is made up of nine clusters, each with nine to thirteen three- to four-story units. The second floor features a glass-walled entrance hall, a multi-purpose space for residents—a true “threshold.” From the entrance hall, two children’s rooms are located side by side. Below the entrance hall, on the first floor, are the living room and bedrooms. As you can see, the houses are structured vertically, with a central entrance that opens to the outside. With Pangyo Housing, I aimed to create a “community within a community.” At first, no one wanted to live in this housing complex, which consists of approximately 100 units (laughs). This was because the second floor was too transparent.

Pangyo Housing, residents gathering on the second floor ©︎Nam Goongsun

This second-floor threshold is like a large entrance hall. It can be used for a variety of purposes, such as a reception room, home office, or studio, and after a while, some residents began to open cafes and galleries there. It seems that many non-residents also visit the space. About four years ago, the residents invited me to a barbecue party. They told me, “Mr. Yamamoto, we live very comfortably here. We enjoy this architecture.”

As an architect, I intentionally created the “threshold” realm, which I learned about from Hannah Arendt and settlements around the world, and I believe that this has created an important place for the resident community. It is here that private life and living are integrated. I’ve introduced some real-life examples at the end. Thank you very much. Vassal: After seeing the actual architectural projects, I was able to better understand what Riken said in his lecture. He looked at ancient Greek plans, Indian and Spanish plans, and the concept of community. What was fascinating was how Riken reinterpreted the various plans presented across time and space in a very contemporary way. I thought this was truly an incredible example of thinking and practice.

Yamamoto: During the modernist era, many apartment buildings and public buildings were built, but I imagine it must have been difficult to form communities or collectives using these methods. However, we learned a lot from this era. That is why we now need to create architecture with ideas that differ from modernism. This Illinois Institute of Technology is truly a symbolic building of modernism, but let’s work together to reach the next stage. Thank you.

Leave a comment