The “Work” of Creating the “Space” Called the “World”-Yamamoto Riken’s Theory

“City Beatiful”, Spetial Edition “Riken Yamamoto Who?”

The “Work” of Creating the “Space” Called the “World”

written by Shuji Funo

Among Japan’s leading architects, Yamamoto Riken is the most “orthodox.” By “orthodox,” I mean an architect who sincerely inherits the original spirit of Japan’s “postwar architecture (modern architecture).” Yamamoto Riken is a sincere architect who, despite being selected as the designer for the Oura Town Hall, Odawara City Civic Hall, and Amakusa City Hall in competitions, filed a lawsuit against the design contract after it was terminated, putting his raison d’être (social proof of existence) as an “architect” on the line. Architects routinely encounter various problems, but “preparing” for each one takes a great deal of energy and has significant drawbacks. Even star architects typically choose to silently tolerate clients’ unreasonableness and absurdity, considering the risk of losing work opportunities. However, Yamamoto Riken always fights back. He constantly challenges the systems that support stereotypical spatial concepts, questioning how to transcend “institutions.” In this sense, an architect who most sincerely embraces and inherits the original spirit of “postwar architecture” is an architect whose work is already being challenged. Yamamoto Riken is at the forefront of this movement.

He may be unassuming. He is not “eccentric” or preaching about “art.” He is a “theorist” who tackles “architecture” head-on. While one could call him a “realist” or “socialist,” he might also be called an “idealist” or “rationalist.” His thinking is rooted in radical questions about the nature of “architecture in society” and “society in architecture.” In the real world of Japan, there is tremendous support from architects who, like Yamamoto Riken, grapple with “architecture” with sincerity. Yamamoto Riken’s winning the 2024 Pritzker Architecture Prize has provided great courage to such architects.

I. An Architect Fighting the System: The Path of Riken Yamamoto

Hinageshi(Poppy)

I first met Riken Yamamoto at the Hara Hiroshi Laboratory at the University of Tokyo’s Institute of Industrial Science, then located in Roppongi. I visited the Hara Laboratory with my “Hina Mustard” colleagues to show a foreign architect around, but we hadn’t made an appointment. Riken Yamamoto, who was alone in the lab, drawing blueprints, greeted us with surprise and confusion at our sudden visit. At the time, my “Hina Mustard” colleagues were in their master’s programs, so this was between 1972 and 1974. In 1970, Riken Yamamoto published the essence of his master’s thesis from Tokyo University of the Arts as “Housing Simulation” (Urban Housing, April 1970). I wrote “An Essay on Territorial Theory” (“Dwelling Settlement Theory I,” special issue of SD, March 1973) in 1973, so I think I was in the middle of summarizing the first part of the Hara Laboratory’s world settlement survey around the Mediterranean region.

Since this first encounter, I have had close ties with Yamamoto Riken through the independent seminar organized by Hara Hiroshi and the “Contemporary Architecture Research Group” centered around Miyauchi Yasushi. At Toyo University, he was a part-time lecturer in design seminars, and we met almost weekly. It was a year-round, on-the-spot design course (Design Seminar IIA), in which assignments were given in the first week and critiques were given in the second week. After we set out assignments and decided on the next assignment, we had endless discussions about the architectural world. Although Riken Yamamoto had made his debut with works such as “Yamakawa Sanso” (1977), he was still relatively unknown. I remember him sketching his GAZEBO (1986) (a pavilion with only a roof and no surrounding walls) while grading works. He also taught part-time at Kyoto University for two years (2000-2001). He also passionately taught students at the University of Shiga Prefecture, saying, “Creating architecture is creating the future” (2007). We are currently working together as editors of the magazine “Toshibi” (launched in 2019).

Yokohama

Born in Beijing and raised in Yokohama, Yamamoto wrote, “We lived in a haphazard house that was far from modern living. Our family structure was also unique. Instead of a father, my grandmother and aunt lived with us, and the aunt had a mild disability. Compared to the average family’s life, I think it’s fair to say it was quite unique.” (“New Edition of Housing Theory,” Afterword, Heibonsha, 2004). There’s no doubt that this family structure is at the origin of Yamamoto Riken’s relentless interrogation of the relationship between family and home.

I’ve heard that his father was a communications engineer, but I’ve never heard much about his upbringing. However, he has a strong attachment to Yokohama. “GAZEBO” (1986) is his family home, and since the founding of Yamamoto Riken Design Factory in 1973, his office, which was located in Daikanyama’s “Hillside Terrace” (1969-1999, Japan Art Grand Prize (1980)) designed by Maki Fumihiko (1928-2024) (Person of Cultural Merit, Member of the Japan Art Academy, Pritzker Prize Laureate (1993)), has been relocated to Yokohama (1997). Furthermore, in 2021, he established a headquarters near GAZEBO, along with the Regional Community Research Institute (general incorporated association).

After serving as a part-time lecturer at numerous universities, Riken Yamamoto was invited to become a full-time professor at Kogakuin University (2002-2007) just before turning 60. He then became the founding principal of Y-GSA (Yokohama National University Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Design) (2007-2011, visiting professor 2011-2013). Born and based in Yokohama, this was the perfect position for the Yokohama-based architect.

Ryozanpaku

After graduating from the Department of Architecture at Nihon University’s College of Science and Technology in 1968, Riken Yamamoto enrolled in the master’s program at Tokyo University of the Arts. After completing his studies, he became a research student in Hiroshi Hara’s laboratory (1971). Why did he choose Hiroshi Hara’s laboratory? At the time, Arata Isozaki (1931-2023) was 40 years old and Hiroshi Hara (1936- ) was 35 years old. The two were idols for students just starting to study architecture and young architects, and Isozaki’s “Toward Space” (1971), Hara’s “What is Architecture Possible?” (1967), and Miyauchi Yasushi’s (1937-1992) “Utopia of Resentment” (1971) were must-read books.

The Zenkyoto movement had its roots in the struggle against tuition fee hikes at Waseda University in 1967, the struggle to prevent the Sasebo Enterprise from docking in January of the following year, and protests against unfair treatment of students in the University of Tokyo’s medical school. It spread nationwide in the wake of the Nihon University 2 billion yen unaccounted funds scandal. At Nihon University, dissatisfaction with the authoritarian regime headed by Chairman Furuta Jujiro exploded, with the first demonstration taking place on May 23, 1968, and the Nihon University Zenkyoto (All-Japan Struggle League) formed on May 27 with Akita Akira (1947-; author of “The Idea of Occupying a University” (editor, 1969) and “Prison Diary: As the Abnormal Becomes Everyday” (1969)) as its chairman. Akita Akira was one year younger than Yamamoto Riken. His classmates in the Department of Architecture included Irinouchi Akira of Toshi Packing Studio (1946-2024; founded the Architectural Planning Institute’s Toshi Packing Studio in 1972) and Hashimoto Isao (1945-; joined Maekawa Kunio Architects in 1970 and is now CEO (2000-present)), who serves as CEO of Maekawa Kunio Architects.

Arata Isozaki has repeatedly spoken of “1968.”

“I may be of the 1960 generation in terms of age, but my way of thinking as an architect belongs to the 1968 generation,” he says. Isozaki Arata’s thinking is consistently rooted in an anti-establishment sentiment toward the “established,” “old system,” “old regime,” and “establishment.” The word “anti” appears in the titles of his books and essays, such as “Anti-Architectural History,” “Anti-Recollection,” and “Anti-Architectural Notes.” He favors words like “violation,” “objection,” “demolition,” “revolution,” and “avant-garde.” It seems clear that Yamamoto Riken has inherited Isozaki’s anti-position. For our generation, who entered university in 1968, the most familiar words are “objection,” “anti,” “rebellion,” “the rationality of rebellion,” and “self-denial.” The reason Isozaki’s writing resonated with the “Zenkyoto generation” was because there was a fundamental commonality between his thinking and his writing. At the time, Liangshanpo was everywhere as a group that challenged the established system, and there were countless encounters.

Going back a little further, from the late 1970s through the 1980s, I had the opportunity to meet Irinouchi Akira and Hashimoto Isao frequently. I have somewhat bitter memories of those times. I was approached by Miyauchi Yoshihisa (1926-2009, architectural critic and editorial journalist. Author of Minority Theory of Architecture, Anti-Architecture Theory from the Ruins, Dissenting Views on Architecture and Urbanism, Outrageous Architectural Journalism, Kunio Maekawa, General of the Rebel Army, etc.), and the editorial committee (Irinouchi Akira, Hashimoto Isao, Nagata Yuzo (1941- ; Worked for Takenaka Corporation in 1965, established Nagata-Kitano Architectural Institute in 1985, established Nagata Architectural Institute in 2007, and author of Hotel Kawakyu (1993, winner of the 6th Murano Togo Prize)), Fujiwara Chiharu, and Koyanagi Jun) had been discussing the possibility of publishing a new architectural media outlet called Chiheisen (working title) to succeed Kaze-sei and Ryoka. I will not go into the details, but the discussions ended in a breakdown. In my personal opinion, Gunkyo was the first publication to be published. As mentioned above, Riken Yamamoto launched Urban Beauty in 2019.

Ueno Forest

At the Tokyo University of the Arts Graduate School, he was a member of the Yamamoto Manabu Laboratory. At the time, he was surrounded by a distinguished group of members. Among his colleagues at the Tokyo University of the Arts Faculty of Fine Arts was Fram Kitagawa (1946-; majored in Buddhist Sculpture History at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts; founded Yuria Pempel Studio in 1971; established the Contemporary Planning Office in 1977; opened Art Front Gallery in 1982; participated in Faret Tachikawa (1994); Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale (2000-present); and Setouchi Triennale (2010-present). He received the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology’s Art Encouragement Prize (2007), the Medal with Purple Ribbon (2016), and was a recipient of the Person of Cultural Merit (2018). Kitagawa Fram’s older sister, Kitagawa Wakana, is the wife of Hara Hiroshi.

The group “Konpeitō”, formed by Ide Ken (1945-2022), Matsuyama Iwao (1945-) (winner of the Mystery Writers of Japan Award for “Ranpo and Tokyo” (1984), the Itō Sei Literary Prize for “Stones in the Darkness” (1996), and the Yomiuri Literary Prize for “The Crowd: Refugees in the Machine” (1997), and Motokura Makoto (1946-2017) (Maki Sogo Office from 1971 to 1976; founded Studio Architectural Planning with Iida Yoshihiko (1950-) in 1980; professor at Tohoku University of Art and Design (1998-2008); professor at the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts (2008-2012); winner of the Kumamoto Prefectural Housing Ryujadaira Housing Complex (1993, 1995 Architectural Institute of Japan Award)), are of the same generation as Yamamoto Riken. “Konpeitō” was well-known to those of us a few years younger than me, along with Musashino Art University’s “Remains Research Institute” (Makabe Tomoharu, Otake Makoto, etc.) and Tokyo University’s “Randium” (Ishii Kazuhiro (1944-2015; “Sukiya-mura” awarded the Architectural Institute of Japan Prize (1989)), etc.). A portrait of the young people of the time can be seen in the “Advertisements for Myself” section, which appears in the latter pages of the “Architectural Yearbook” (1968, Miyauchi Yoshihisa Editorial Office). I met Ide Ken and Matsuyama Iwao of “Konpeitō” at “TAU.” These two and “Hina-Kakeshi” continued to hold study sessions on several occasions. Led by Miyake Riichi, who is fluent in French, we read the original works of French Revolutionary-era architects Ledoux, Bouley, and Lucques. It was at Maki and Associates that I met Motokura Makoto. During graduate school, I worked part-time at Maki Office for one month during summer vacation, accompanied by a senior student on his first tour of the building. It was there that I met Makoto Motokura. It was a strange coincidence.

Makoto Motokura and Riken Yamamoto ended up sharing an office space (field shop) on the bottom floor of Hillside Terrace.

Hara Hiroshi Laboratory

After graduating from Toyo University, Hiroshi Hara was invited by Akira Ikebe (1920–1979) (graduated from the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Tokyo Imperial University in 1942, joined Itakura Architects in 1944, lectured at the Second Faculty of Engineering, Tokyo Imperial University in 1946, participated in the founding of the New Japan Architects Association (NAU) in 1947, was an associate professor at Tokyo Imperial University in 1949, and professor at the Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo in 1965) to return to the Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo, as an assistant professor. This was in the midst of the “University of Tokyo Struggle.” I read “What is Architecture Possible?” (1967) at a reading group in the drafting room in Hongo with my fellow members of “Hina-Kakeshi.” I then read M. Ponty’s “Phenomenology of Perception,” but found it equally difficult to understand. However, the question “What is Architecture Possible?”, along with the slogan “Everything is Architecture” (H. Hollein (1934-2014)), excited architecture students. He is known for numerous works, including those by the RAS Design Group, such as the Ito Residence (1966) and Keimatsu Kindergarten (1968), and his theory of “porous bodies” was truly fascinating.

As a result, Yamamoto Riken became Hara Hiroshi’s most talented student. It can be said that it was Yamamoto Riken who founded the Hara Laboratory at the University of Tokyo together with Irinouchi Akira, who had joined the Hara Laboratory earlier. Members of the Hara Laboratory at Toyo University included Ogawa Tomoaki, who would later become the driving force behind Atelier Phi, and Yamatani Akira. Hara’s laboratory has produced a succession of researchers, including Motomu Uno, Kengo Kuma, Satoshi Takeyama, Kazuhiro Kojima, Hidekuni Magaribuchi, Kotaro Imai, Hiroshi Ota, Yasuhiro Minami, and Osamu Tsukihashi.

Hara Hiroshi and Hina Mustard met at a symposium hosted by Hina Mustard, and at Hara’s invitation, they began an independent seminar. Hara’s circle, along with the Art Front led by Fram Kitagawa, also formed a Liangshanpo. Art Front ran a bar called Kasaya in Sakuragaoka, Shibuya, where they would gather night after night. Soon, a slightly younger generation, including Nobuaki Furuya (1955-; recipient of the Architectural Institute of Japan Award for Chino Civic Hall (2007); President of the Architectural Institute of Japan (2017-2018)), joined the study group. When Hina Mustard advanced to graduate school, the University of Tokyo and the Tokyo Institute of Technology had a credit transfer system, and there was interaction between Hara Hiroshi’s laboratory and Kazuo Shinohara’s laboratory. At the time, Hasegawa Itsuko (1941-) (founded the Hasegawa Itsuko Architectural Planning Studio (1979); “Bizan Hall” (1986, Architectural Institute of Japan Award, no longer in existence), “Shonandai Cultural Center” (1989), “Yamanashi Fruit Museum” (1995), etc.) was a research student in the Shinohara Laboratory, and we met occasionally.

When I was in my second year of master’s studies, an “incident” occurred when my supervisor, Yoshitake Yasumi, was suddenly transferred to the University of Tsukuba just before retirement (at the age of 57). Hara Laboratory

I was invited to join the group, but circumstances prevented me from moving from Hongo. Some of my fellow members of Hina-Kakeshi left Japan (to study abroad) and found jobs, and I began frequenting another Liangshanpo group: the AURA Design Studio, run by Miyauchi Yasushi, a junior of Hara’s at Iida High School in Nagano Prefecture and a member of the RAS Design Group.

World Village Survey

Hara Hiroshi’s laboratory’s “World Settlement Survey” was conducted five times throughout the 1970s: in the Mediterranean, Latin America, Eastern Europe and the Middle East, India and Nepal, and West Africa. Yamamoto Riken participated in the Mediterranean, Latin America, and India and Nepal tours, and wrote three papers: “An Essay on Territorial Theory,” “Limit Theory I,” and “Limit Theory II.” All of these are included in “Housing Theory,” and Yamamoto himself often points out that the World Settlement Survey forms a major foundation for his housing theory.

It is clear that this global village survey was a great source of inspiration for Hara Hiroshi and other participating members, including Takeyama Satoshi. Since “What is Architecture Possible?”, Hara Hiroshi has not written many books. His most important collection of architectural essays is “Space: From Function to Aspect” (1987). His more comprehensive works include “A Journey to the Village” (1987) and “100 Lessons from the Village” (1998). In the 1970s, Hara Hiroshi designed only residential works such as the Awazu Kiyoshi Residence (1972), his own residence (1974), and Matsukeyaki Hall (1979). There was virtually no work during the 1970s, which saw two oil crises. The methodological awareness of “embedding the city in the home” was deeply shared by young architects. The Hara Laboratory’s “World Settlement Survey” can be seen as an extension of the “design surveys” pioneered by Kamishiro Yuichiro (1922-2000) and Miyawaki Dan (1936-1998), that is, as belonging to the movement that emerged after B. Rudofsky’s discovery of “architecture without architects.” However, by effortlessly crossing national borders and blasting through the vast world like a gale, it has brought an entirely new perspective to the Japanese architectural world.

I began traveling around Asia in 1978 after taking a position at Toyo University, where Hara Hiroshi had previously worked. From January to February 1979, I traveled to Indonesia and Thailand. Then, in August, I went to the Philippines and Malaysia with Uno Motomi, who was also a member of the Hara Laboratory, and this was the starting point of my Asian studies. The immediate trigger for this project was the launch of a research project titled “Theoretical and Empirical Study of Housing Issues in the East” with fellow members including Naomi Maeda, Kunio Ota, Kei Uesugi, and Yuzo Uchida (1942–2011). The Hara Laboratory’s “World Village Survey” was a major inspiration. The profound impact it had on the architectural community as a whole is evidenced by the “Methods and Issues of Residential Village Research: Concerning Cross-Cultural Understanding,” a research conference I organized for the Architectural Institute of Japan.

GAZEBO: A Residence Above a Multi-Tenant Building

Riken Yamamoto established the “Yamamoto Riken Design Factory” in 1973. His debut work, “Yamakawa Villa,” was completed in 1977. His architectural training and his world village survey overlapped. In fact, “Yamakawa Villa” was preceded by the “Sanpei Residence” (Kanazawa Ward, Yokohama, 1976). Regarding this work, Yamamoto Riken wrote the following (“Design Work Diary 77/88 – As a Personal Study of Architectural Planning,” “Special Feature: Yamamoto Riken’s Architectural Planning 77/88,” Architectural Culture, Shokokusha, August 1988): “In short, it was all new to me, and I built this building without knowing anything. After graduating from graduate school, I immediately went to Hara’s lab and set up an office, so I started it all by myself, so I had no practical experience whatsoever. The scary thing is that I designed it with that in mind. So this studio doesn’t have any insulation. I didn’t know that… I didn’t think of practical experience as much. No matter how much experience you accumulate, ultimately, you only get to a certain point. It felt like it was unrelated to the central issues of architecture.” Before architecture was something concrete, it was first an object of thought. Having just returned from the Hara Laboratory’s first village survey, I had been thinking of it as a spatial arrangement, as it appears on a floor plan. It seems that in my mind it had become completely abstract.

From “Yamakawa Villa” to “GAZEBO” (1986), when he won the Architectural Institute of Japan Award in 1988, Yamamoto Riken continued to design small, residential projects, such as the “Kubota Residence” (1978), “Yamamoto Residence” (1978), and “Fujii Residence” (1982).

I can attest that he wasn’t particularly busy during this time. As mentioned above, he came to Kawagoe every week as a part-time design and drafting instructor at Toyo University. I was solely responsible for on-the-fly designs, and in addition to Yamamoto Riken, I also had other architects, including Kezuna Takehiro, Motokura Makoto, and Uno Motomu, come in on a rotating basis. We worked on one project every two weeks, completing the on-the-fly designs and then conducting thorough judging the following week. The first week, after handing out assignments, I was pretty bored, so we had lunch at a nearby soba restaurant and chatted about Japanese architecture. It was really fun. And thinking up assignments was stimulating.

I have dozens of them in stock, but my masterpieces are “Parasite on the City” and “The House Where the Mistress Lives” (“The Reverse Jet Family”). Yamamoto Riken writes in detail about “The House Where the Mistress Lives” in “Theory of Residential Mischief.” I remember Rokkaku Onijo, who came to my lecture, scratching his head and asking, “What! What is this assignment?” You could call it a kind of thought experiment, but removing just one realistic condition can remarkably stimulate and liberate your architectural imagination. “Imagine the land suddenly rises 50 meters,” “Imagine you get hold of a piece of land about 6.6 square meters in front of Shibuya Station,” “Bury the Pantheon underground and use it as a nuclear shelter”… We came up with one assignment after another together. While assigning these assignments to his students, he said, “It’s about time we started designing them,” and sketched out the resulting “Gazebo,” a “residence above a multi-tenant building,” and “Rotunda” (1987), which won his first Architectural Institute of Japan Award (1987). This was followed by the completion of “HAMLET” (1988), and the compilation of his early works, “Special Feature: Riken Yamamoto’s Planning Studies 77/88” (Architecture Culture, August 1988), solidifying his reputation.

Onward to Public Architecture Competitions

The Architectural Institute of Japan Award also paved the way for Riken Yamamoto to design public architecture. The next major milestone was the “Kumamoto Prefectural Hotakubo Daiichi Housing Complex” (1988-1991), which marked his next major breakthrough. Meanwhile, the number of submissions to design competitions also increased, with projects such as Nago City Hall (1978), Komagane City Cultural Park (1984), the Japan-France Cultural Center (1990), Kawasato Village Hometown Hall (1990), Kamo Town Cultural Hall (1992), Saitama Prefectural Museum of Modern Literature (1993), and Kumagaya City Second Cultural Center (1994).

After the Kumamoto Prefectural Hotakubo Daiichi Housing Complex and Okayama House (1989), opportunities also arose to design planned housing complexes, including Ryokuen Toshi (1992-94) and Shinonome Canal Court CODAN (2003).

The Kumamoto Prefectural Hotakubo Daiichi Housing Complex caused a huge stir, with coverage in newspapers and on television. Residents were perplexed by the planning, in which rooms were connected to each other through the exterior. The design of the central plaza (common), accessible only to residents, was criticized as being overbearing by the architect. Many critics responded with the same old cliché: “Life is being sacrificed for the sake of design.” However, within the architectural community at least, this was seen as an endeavor that an architect should undertake. From then on, he was blessed with opportunities to design public buildings.

His next step was winning the competition for Iwadeyama Junior High School (1996) (receiving the Mainichi Art Award in 1998). He solidified his position with Saitama Prefectural University (1999) (receiving the Japan Art Academy Award in 2001). He and Toshihiko Kimura received their second Architectural Institute of Japan Award for Design in 2002 for Future University Hakodate (2000). I was one of the judges for this award.

Riken Yamamoto’s approach remains the same when it comes to junior high schools and universities. His consistent approach is to thoroughly examine the relationship between the institution and space.

He has not yet worked overseas. The first was the Jian Wai SOHO (2003), perhaps due to its origins in Beijing. This was followed by the Pangyo Housing complex in Seongnam, South Korea (2010), the Tianjin Library (2012), the Gangnam Housing complex in Seoul (2014), and The Circle – Zurich International Airport (2020).

Since Iwadeyama Junior High School, the company’s success rate in competitions has been quite high, demonstrating that its sharp proposals accurately struck at the roots of Japanese society. However, major obstacles to this direction were the issues surrounding the Oura Town Hall (2005), as well as the Odawara Castle Town Hall (Odawara City Civic Hall) (2007). Furthermore, the Amakusa City Main Hall (2013) won the top prize in its proposal competition, but was canceled due to factors such as a change in mayor.

II. Family Form and Social Form – Yamamoto Riken’s Architectural Theory

Yamamoto Riken has persistently questioned the forms of family and housing, as well as the forms of social institutions and space. This fundamental question for this architect has consistently persisted since his debut work, “Yamakawa Villa,” and has been pursued in the context of housing, from “GAZEBO,” “ROTUNDA,” and “HAMLET” to “Kumamoto Prefectural Hotakubo Housing Complex,” “Okayama Housing,” and “Shinonome Canal Court CODAN.” He has also expanded this inquiry to public buildings such as schools, universities, and town halls.

Yamamoto Riken’s fundamental approach as an architect is closely aligned with architectural planning, which examines the correspondence between spatial forms and lifestyle patterns. Yamamoto Riken titled his first magazine feature compiling his early works “Yamamoto Riken’s Architectural Planning 77/88” because he was conscious of “architectural planning.” The subsequent compilation of “A Box That Houses a Family, a Box That Surpasses a Family” (2001) around “51C” also demonstrates our shared foundation. One of the reasons I have maintained a strong sympathy for Yamamoto Riken from the beginning is that I graduated from the architectural planning laboratory (Yoshitake Yasumi and Suzuki Shigefumi).

Yamamoto Riken does not write what is commonly called architectural theory or architect theory. He does not provide comprehensive essays on the great masters of modern architecture, historical masterpieces, or architects of his generation. He also hardly develops what is generally called theory of expression or technology. In this sense, he may be considered a unique architect. The majority of his essays are on housing. However, his housing theory has a common structure that directly connects to architectural theory and urban theory.

Let’s examine the framework and basic concepts of his housing theory, focusing on two books: “New Edition of Housing Theory” (2004), which includes “Housing Theory” (1993), and “The Possibilities of Architecture: The Yamamoto Riken Imagination” (2006).

“Area,” “Threshold,” “Roof”

Riken Yamamoto’s starting point was “dwelling group theory” based on the “World Settlement Survey.” Even before that, he developed a “dwelling simulation” model based on his master’s thesis, which he describes as “the beginning” (“Introduction” to “New Edition: Housing Theory”). From the beginning, Yamamoto has consistently maintained a fundamental perspective that persistently interrogates the arrangement of dwellings, a space familiar to everyone. As mentioned above, I believe the origin of his thinking lies in the gap between the family relationships of one’s origins (the family one grew up in, the home one lives in) and the family and housing forms that are considered (or are taught) standard in society.

Hiroshi Hara is primarily interested in explaining the arrangement of residential groups through mathematical models, while at the very least, he is prepared to express the findings of his settlement surveys at various levels or directly link (return) them to design methods. There are several speculations as to why Hiroshi Hara turned to the “World Settlement Survey.” I have felt quite uneasy about, and even discussed, the academic significance of, a survey that sweeps through settlements like the wind. My research on Asian cities (urban tissue research, urban housing research) is an extension of that discussion.

Yamamoto Riken is thoroughly principled. In his “Tentative Theory of Territory” (SD Special Issue 6), he distinguishes between three types of settlements (residential clusters). These three types — “Petres Type,” “Cuevas Type,” and “Medina Type” — are merely conceptual classifications of the “clarity/ambiguity” of territory in dwellings and residential clusters, but they are not simply schematic typologies in that they classify settlements that were actually surveyed. The three residential cluster shapes are actually possible.

In this paper, the concept of “threshold” is introduced along with the concept of “territory,” and “Limit Theory I” and “Limit Theory II” explore this concept to their fullest. This theory of “threshold” is at the heart of Yamamoto Riken’s theory of housing.

In everyday language, “threshold” means “threshold” or “entrance.” The “boundary” between two “territories” is a “threshold.” A “territory” is a space that contains certain characteristics, a “place” that is enclosed by a “boundary.” The characteristic is the unity of a “group,” and one “territory” realizes the unity of only one group. It is not possible for multiple groups to realize the unity of one “group.”

If we define “territory” in this way, it means that “two or more ‘territories’ cannot intersect and exist side by side.” However, when a settlement (a collection of residences) is a “territory” and each individual residence is also a “territory” (a Petre-type settlement), a “space” or “device” is needed that “allows the ‘territories’ to come into contact with each other without interfering with each other.” This is a “threshold.” Specifically, a “threshold” is a space such as a “foyer,” “windbreak,” or “airtight room.”

While this somewhat diminishes the diverse breadth of the argument, the above is the gist of the argument, if simplified. Yamamoto sees the “threshold” as a “spatial device for maintaining order within a closed area and communicating with the outside world” — a “device.” Furthermore, in “Limit Theory II,” titled “Considerations on the Roof,” he proposes the concept of “roof” as a “unit” that “transcends function and abstracts the scale of family, kinship, and blood-related groups,” and as “a concept that applies to all closed areas ordered by thresholds,” thereby developing a more flexible conceptual model. One concrete example of the concept of “roof” that applies to all closed areas is the village-city pattern of the South Indian architectural text “Mānasāra.” The contrast between the world of “Mānasāra” (the principles of the “mandala city”), which views dwellings, settlements, and cities as a single closed order and as an embodiment of the worldview/cosmology of the people living in the area, and the principles of the “Islamic city” we will discuss later, is key to Yamamoto Riken’s theory of territory.

Deconstructing the Prototype

Based on his “threshold” theory, Yamamoto Riken’s theory of housing presents two theses:

“The family community is a community within a community.”

“The residence is a spatial device for controlling the encounter between these two communities, the family community and a higher-level community.”

Given this incredibly simple thesis and principle, and the diverse residential communities revealed in the “World Settlement Survey,” Japanese housing appears far too uniform. His “Housing Mimicry Theory” (serialized in “Shichi-no-Shi”, March, May, July, and September 1992) sharply indicts this frightening uniformity and the stereotyped fantasies about lifestyle and family that support it. His design projects, “A House with a Lover” and “A House for 100 People,” invite reflection on the mimicry of family and housing. Furthermore, the “Okayama House” (1992) was constructed as an actual prototype and model. However, Yamamoto Riken had already attempted to criticize stereotypical residential forms in his “Yamakawa Villa.” While it is a summer-only villa, it nonetheless presents one form of residential architecture. Its exposed wooden floors evoke the Korean “maru” (main hall) or “daecheon” (main hall). It also evokes the “Sumiyoshi Row House” (1976, 1979 Architectural Institute of Japan Award) by Tadao Ando (1941-) (Japan Art Academy Prize (1993), Pritzker Architecture Prize (1995), Praemium Imperiale (1996), RIBA Gold Medal (1997), AIA Gold Medal (2002), Person of Cultural Merit (2003), UIA Gold Medal (2005), and the Order of Culture (2010)). The 1970s was a time when the postmodern generation produced a succession of residential works. This was by no means a “period of wild flowering” (Housing: Wild Flowering in the 1970s, Ex-Knowledge Mook, 2006), but rather an expression of a tectonic shift in Japanese society as it sought new forms of housing. What we must remember is that thoroughly questioning the familiar spatial form of the home was the starting point for an “architect” to become an “architect.”

The Shindo House, Kubota House, and Ishii House, which were published in Shinkenchiku (August 1978) along with Yamakawa Villa, appear to be unrelated at first glance. Toyokazu Watanabe (1938-) (Ryujinmura Gymnasium, winner of the Architectural Institute of Japan Award (1987)) is said to have described them as “schizophrenic.” Toyo Ito (1941-) (Architectural Institute of Japan Award (1986, 2003), Japan Art Academy Award (1999), Golden Lion at the Vezia Biennale (2002), RIBA Gold Medal (2006), Praemium Imperiale (2010), Pritzker Architecture Prize (2013), Architectural Institute of Japan Grand Prize (2016), Person of Cultural Merit (2018), Member of the Japan Art Academy (2022)) also commented that “their appearance styles are quite different” (Systems Store). Details of Architecture (2001). However, based on Yamamoto’s “Limit Theory,” it does not seem so strange. This is because it can be one of several possible answers to the question of “Housing as Form” (Shinkenchiku, August 1978). We will look at the issues of “style” and “architectural expression” in Yamamoto Riken later. What sets Yamamoto Riken apart from other architects, such as Ito Toyo, is that he is a thorough critic of the standardization and stereotyping of housing. The point is that he does not limit himself to criticism, but rather presents a new prototype. He is different from Toyo Ito, who said, “For me, architecture without an archetype is ‘ideal architecture,’” and Fujimori Terunobu, who wanted to create “architecture that has never been seen before.”

“GAZEBO: Residence Above a Multi-Tenant Building” presents a prototype. It is one answer to the question of how a residence can be established in a commercial area along a main road. It can be said that this attempt is comparable to the “Sumiyoshi Row House.” In a world where all space is governed by economic principles (the commodification of total social space), this model embodies the determination to “not give up the top floor” (“bankrupt city”).

The “Okayama House” was designed as a model for a single-family home, and the “Hotakubo Housing Complex” was designed as a model for apartment complexes. Yamamoto Riken’s response to the residence As can be seen above, it is clear that this approach is truly “orthodox.”

Cellular City

Yamamoto Riken’s theory of territory—and that of many “architects”—is premised on the idea that settlements, cities, and the world are constructed through the expansion and layering of clusters of spatial units known as dwellings. While this is a completely different construction from a perspective that emphasizes the infrastructure that supports space, such as in civil engineering, for Yamamoto, infrastructure is also a “threshold.” Furthermore, theories of “thresholds” and “roofs” are flexible in scale. Therefore, his theory of housing can be expanded to include architectural theory, urban theory, and so on. Furthermore, Yamamoto Riken has a particular perspective on cities (see “2006: In-Depth Discussion: The City We Want to Live In” (ed.) (2006)).

The commercial district plan for Yokohama’s “Ryokuen Toshi” was the first step in its expansion into the city. Yamamoto Riken presents the concept of the “cellular city” (Cellular City, INAX, 1993; Cellular City, English version (System Environment Research Institute), 1999; Cellular City, French version (French Association of Architects), 1999). The specific model for the concept of the “cellular city” is the “Islamic city,” which is “improvised and lacks a clear overall plan” (“Cellular City,” in “The Possibilities of Architecture: Yamamoto Riken’s Imagination,” Okokusha, 2006). “Islamic cities” are “not cities that are gradually built up towards a final form, but cities that are completed as they are built.” Yamamoto’s interest in “Islamic cities” can also be traced back to the first “World Settlement Survey,” the Mediterranean. While Yamamoto does not go into the details of specific structural principles, he does refer to B.S. Hakim’s “Islamic Cities: Principles of Arab Town Planning” (translated and supervised by Sato Tsugitaka, Daisan Shokan). was published much later, so his focus on “Islamic cities” was an early and insightful one.

A “cellular city” is a city “in which each building is both a factor and a cell of the city.” A building as an “urban cell” is “a building that, at the same time, contains within it the opportunity for growth into a city.”

The “Ryokuen Toshi” approach is “not to first create an overall plan and then restrict individual buildings according to that plan; in other words, not to create buildings that are components of the city as a whole, but…to think of buildings that contain within themselves the factors that will allow for continuity when buildings continue one after the other.”

However, in the case of Ryokuen Toshi, the “factors” are actually quite simple. The “factor for continuity” is to create a through-path for every building to connect to adjacent buildings. Of course, this does not mean that each building simply needs to have a through-path. The principles of the “Islamic city” have the ability to create a more enriching spatial experience.

Work-Sleep Integrated SOHO

After gaining experience with the Kumamoto Prefectural Hotakubo Housing Complex and Ryokuen Toshi, I was given the opportunity to design Shinonome Canal Court CODAN (2003). This led to the opportunity to design Jianwai SOHO (Beijing). Designing overseas (in a different culture) also provides an excellent opportunity to test the universality of “liminal theory.” While the Tianjin Banshan House (2005) and the Amsterdam Housing Complex (2008) were not realized, Pangyo Housing (2010) followed.

However, of course, theory and reality differ. It is actually more common for ideals not to be realized exactly as they are. In the case of Ryokuen Toshi, it could be said that the best they could do was to incorporate the “throughway” as a factor.

Shinonome Canal Court CODAN is a project of the Urban Development Corporation (now the Urban Renaissance Agency). Its predecessor was the Japan Housing Corporation, Japan’s largest public housing provider, and has supplied prototypes for Japan’s postwar housing. I will not go into detail about its historical and social role here, but there is no doubt that it was inevitable that a group of renowned architects including Yamamoto Riken would be chosen for the project. After half a century of history, it is clear that their housing model has become out of sync with societal needs.

Yamamoto Riken wanted to try out the idea of ”placing the kitchen and water section, such as the washroom and bathroom, closer to the window.” He thought that doing so would enable a variety of living styles, such as using the space as an office or sharing a large unit with friends. He proposed this when asked to build a private condominium, but it was not realized. This was because the developer believed that “it lacked the general appeal of detached housing,” meaning that “because detached housing is purchased as a kind of asset rather than as a residence, it would not sell unless it was general enough to suit everyone” (“The Social Aspects of Architecture,” JA 51 Riken Yamamoto 2003, Shinkenchiku-sha, September 2003).

While the corporation was also a developer, as it was offering rental housing, there was room for it to take social needs into greater consideration. Furthermore, the corporation was under social pressure to not allow any vacant homes to be built.

Shinonome Canal Court CODAN, which consisted of 70% family-type units and 30% proposal-type units, was a success, with an average application rate of 24 times. The reason for its success was not necessarily the type of “plan.” Yamamoto Riken’s calm analysis posited that the main reasons for this were the “integrated living and work environment” and “mixed living and work environment” (“‘Integrated Living and Work Environment’, Quarterly Design No. 5, October 2003).

What did Yamamoto Riken accomplish with Shinonome? Reading his three-way conversation with Ito Toyo and Sogabe Masashi, “Discussing Shinonome Canal Court CODAN” (Shinkenchiku, September 2003), one gets a good sense of the struggle.

The housing market had already responded to the SOHO (Small Office/Home Office) lifestyle with “designer apartments.” Yamamoto Riken’s vision wasn’t just for a “slightly stylish” design, but for a model of “integrating work and sleep.” His overall conclusion was that he had “accomplished something” and “still only halfway there.”

Criticism of “51C”!?

I had the opportunity to tour the Shinonome Canal Court CODAN construction site. It was a huge success, packed with people, including students from Kobe Design University led by Suzuki Shigefumi. The discussion, which included a casual beer party, was lively, and we all stormed over to Suzuki Shigefumi’s residence in Shin-Otsuka, where we drank until the early hours. Before I knew it, I was in Yokohama.

The discussion that day led to the planning of a symposium, and the results of that discussion became the book “51C: Boxes that House Families, Postwar and Present” (Heibonsha, Suzuki Shigefumi, Ueno Chizuko, Yamamoto Riken, et al., 2004). The person who oversaw the entire discussion was Tajima Kimie, a former student of Professor Suzuki and former student at Suzuki’s home. After becoming a research student in my lab at the University of Shiga Prefecture, she went on to pursue a doctorate at Osaka University and currently teaches at Akashi Technical College.

A major focus was the evaluation of “51C,” and another was the criticism of the idea that “architects” are “spatial imperialists,” spearheaded by Ueno Chizuko (1948- ).

I would like to leave the full discussion to “51C: Boxes that House Families, Postwar and Present.” So I wrote an article titled “51C: Its Reality and Illusion – Postwar Japanese Housing and Architects.” The conclusion reads as follows:

“When I began traveling around Southeast Asia in 1979, I was deeply impressed by a housing supply method known as self-help housing or housing by mutual aid. I recall being particularly enlightened by a housing supply method known as the Core House Project.

The Core House Project is a method in which only a studio apartment and a bathroom (toilet and sink) are provided, and the rest is left to the residents. They are free to add on as they wish, according to their financial means. The layout is flexible. Given limited financial resources, this is unavoidable ingenuity. The form of the Core House is primitive, but incredibly diverse. It reminded me of the 51C and “minimal housing” that emerged in Japan shortly after the war. Surely there could have been countless alternatives? Later, I had the opportunity to consider a model for collective housing in Indonesia (The World of Kampung, 1991). The result was an Indonesian version of a collective house with a common living room and kitchen. It’s clear that Japanese housing, which simply involves stacking or lining up nLDK units, is rather unique.

The key is the logic of collection, or shared space.

Since “51C,” Suzuki Shigefumi’s work has consistently focused on the logic connecting residential collections and shared spaces, the “home” and the “town.” The question of whether he has fully developed this is also a theme he must take on himself. We can calmly assess whether Yamamoto Riken’s Hodakubo Housing Complex and Shinonome’s proposals surpass “51C.”

Ueno’s criticism of the modern family is radical. However, the fiction of the modern family is also solid, backed by various institutions. And housing, too, is extremely conservative. At the same time, however, it’s clear that a society structured around nLDK spatial units cannot accommodate increasingly diverse family relationships and increasingly fluid social structures.

So, what kind of spatial model is possible? Architects continue to be asked this question on every occasion.

III. Creating Architecture is Creating the Future – Riken Yamamoto’s Design Method

Riken Yamamoto is a theorist through and through. He is also a sharp social critic who questions the rational nature of society and space. Unlike Arata Isozaki or Toyo Ito, he does not position himself by assessing trends in the global architectural world. He uses architecture as a medium to propose ways of organizing social space, making him truly a “social architect.” However, it is clear that theory cannot have great influence if it remains solely theoretical. Architectural theory gains its impact by demonstrating the realization of concrete architecture.

Riken Yamamoto’s theories on housing and architecture, however, lack a “theory of expression.” The pursuit of spatial and construction systems is the basis of his design method. While this may be considered a weakness, it does not mean that Riken Yamamoto’s architectural expression lacks power. His theories are based on expressive power, drawing people’s attention to their own unique theories. And at their foundation lies the following profound question: “In what way can my emotional attachment to my expression transcend ‘me’? Is it something that can achieve some degree of universality, or is it something that can be contained solely within ‘me’? How can my way of speaking about my expression transcend the emotional attachment that is unique to ‘me’, that is, the uniqueness of ‘me’? Unless I can break through that barrier, I feel that no way of speaking about my expression will have any effect on anyone other than ‘me’. In other words, how does my expression resonate with people? What is the mechanism behind this? Unless I can clarify this, I cannot say anything about my expression.” (“Personal Architectural Planning,” original title: “Design Work Diary 77/88 – As a Personal Architectural Planning,” Architectural Culture, August 1988)

Materials Embedded with the Memory of Technology

In response to the above question, Riken Yamamoto believes that “materials” may offer a clue. As mentioned above, his early residential works were criticized as “schizophrenic” (Watanabe Toyokazu), but he candidly reflects on the trial and error he went through when he first began his architectural career: “Rather than running away by saying that the logic of ‘expression’ and the logic of ‘observation’ are completely separate, perhaps I could find a common ground somewhere. It seemed to me that interpreting materials could be a way to approach ‘expression.’”

Take the Fujii Residence, for example. The intention was to build a lightweight steel frame on top of a reinforced concrete structure, but it ended up being made of wood. I was reminded of a work by Louis I. Kahn (1901-1974), but it seems that wood construction was not his original intention. I was surprised that simply using wood as pillars and beams gave the building a “Japanese” appearance. I believe this is not based on the properties of wood, but rather on the history that wooden construction has carried, and our “memories.” And now, as the seriousness of the problems of climate change and global warming becomes clear, reconsidering wooden architecture is a major challenge for architects.

I would have liked to see further exploration of the performance of Yamamoto Riken’s wooden architecture, but unfortunately, it has not been explored in depth since then. What is clear, however, is that “greenwashing” architecture (a whitewashing of carbon dioxide reduction) that simply involves sticking together pieces of wood is completely unrelated to Yamamoto Riken.

Based on steel, glass, and concrete—the industrial materials that have underpinned modern architecture—Yamamoto Riken seems to have established a certain style in his “GAZEBO,” “ROTUNDA,” “HAMLET,” and “Hotakubo Daiichi Danchi.”

The key is the “roof.”

Even “GAZEBO” might have remained a mere “diagrammatic” building without its gently curving vault roof. Of course, Yamamoto Riken has not been solely concerned with “roofs.” Rather, he has honed his refined grid configurations, rigid-frame structures, and steel details. After the rise of postmodernist architecture, it was Yamamoto Riken’s refined structural systems and details that established him as a standard-bearer of neomodernism. However, while his subsequent “Aluminum Project” (2004) can be understood as an extension of this, his subsequent works, such as the “Kogakuin University Hachioji Campus Student Center Design Proposal (Draft)” (2005), “N Research Institute” (2008), and “Castle Town Hall (tentative name)” (2009), show a somewhat different development. At the time, I wondered whether his previous direction had begun to waver, or whether he was on the verge of discovering new territory.

Systems Structure as a Temporary Construction

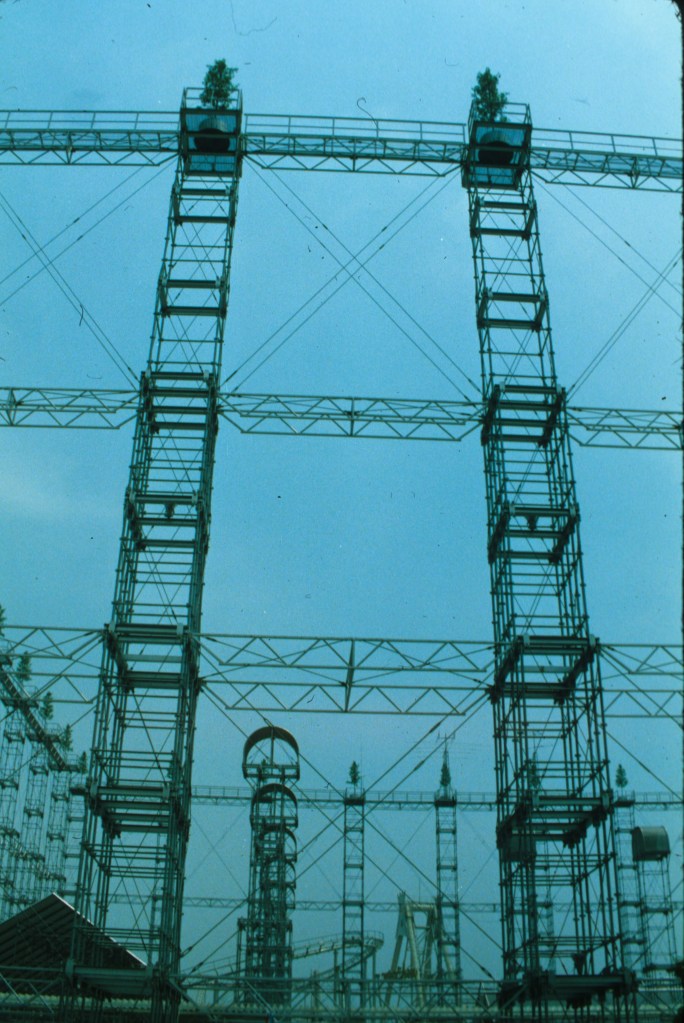

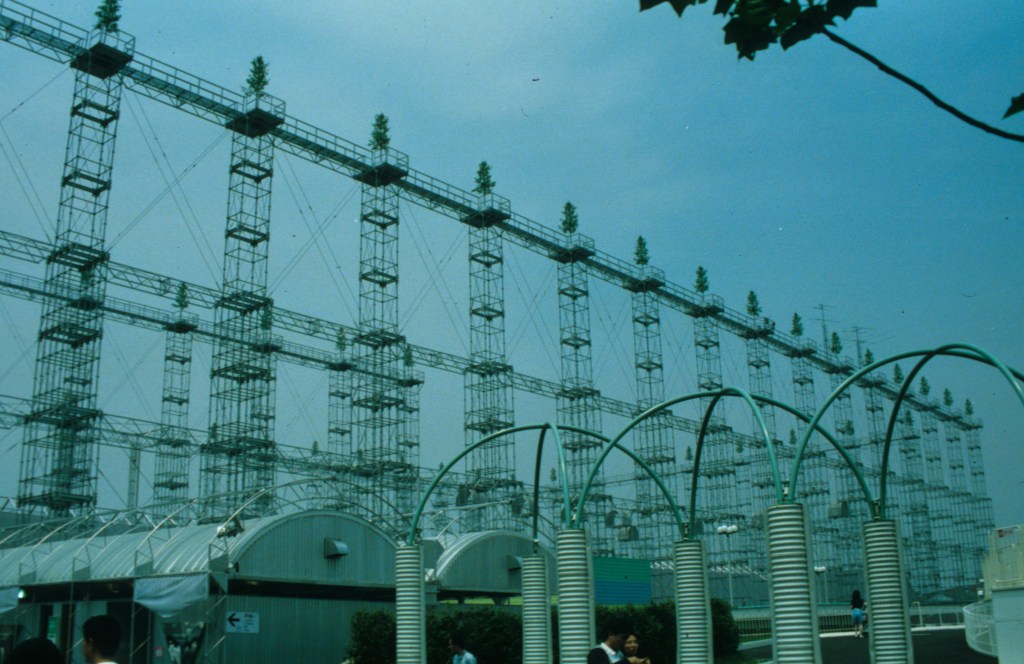

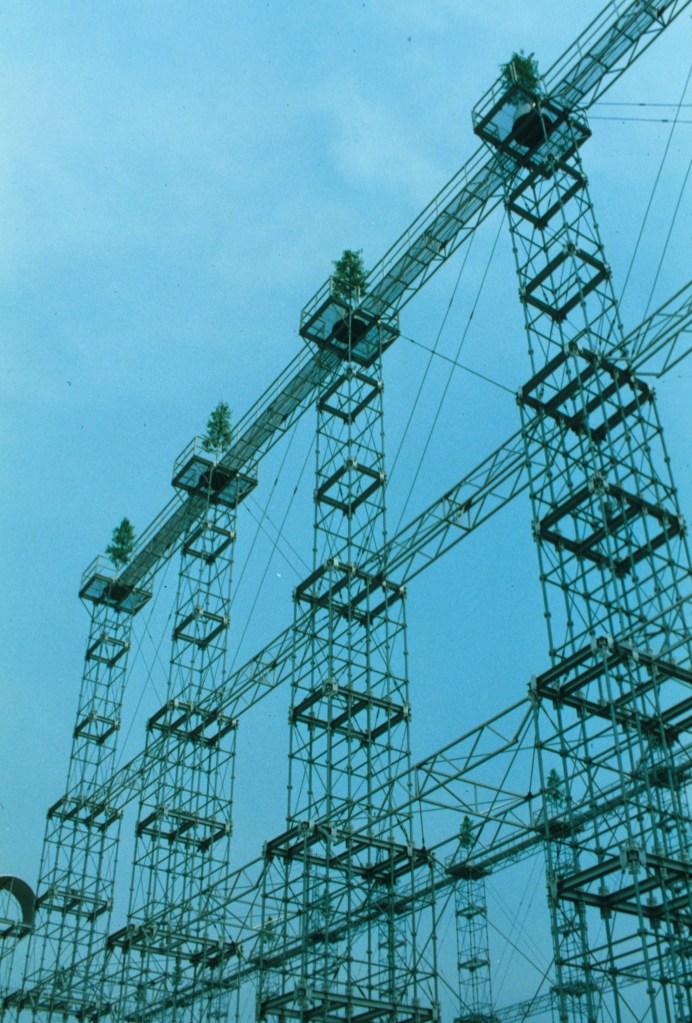

Yamamoto Riken’s first public building was, in fact, the “Takashimacho Gate” (1986) for the Yokohama Expo. “Until then, I had never looked at anything I had created and thought it was beautiful or amazing, but when I saw this architecture, an object-like, phenomenon-like event, I truly found it beautiful” (Cell City).

When I saw Takashimacho Gate, I also thought it was truly beautiful.

Forty 28m-high towers were constructed from 60.5m diameter scaffolding pipes. The materials were too fragile and wobbly to build 28m-high towers, so the towers were linked together to form a super-ramen structure. Such a rich range of expression is possible with a limited variety of materials, mass-produced, and commonly used parts. Takashimacho Gate was the prototype for Yamamoto Riken’s “Systems Structure” (Details of Systems Structure, Shokokusha, 2001). Tatsuo Ono (1940-2023), president of Nisso Sangyo, which provided the scaffolding, launched a campaign to establish a university for craftsmen from 1990 onwards. This movement resonated with Yoshiya Uchida (1925-2021), a member of the Academy, professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo, and recipient of the Architectural Institute of Japan Grand Prize (1995). At his behest, I participated alongside Fumio Tanaka, Koichi Fujisawa, and Masao Ando. This connection is also present.

In his projects for Iwadeyama Junior High School (1996), Saitama Prefectural University (1999), Hiroshima City West Fire Station (2000), and Future University Hakodate (2000), he consistently pursued a simple rigid frame grid using steel frames and precast concrete (PC). Yamamoto Riken’s status as a legitimate successor to postwar modernism is based primarily on his pursuit of systems structure and its details. There’s something in common with his spirit of pursuing industrialized construction methods with the aim of low cost.

While glimpses of this can already be seen in his pursuit of detail using prefabricated steel round pipes in “GAZEBO,” “ROTUNDA,” and “HAMLET,” his references to 19th-century industrial products and Viollet-le-Duc are also intriguing. His dialogue with Toyo Ito in “Details of Systems Structure” is fascinating, revealing the difference in their stances toward systems. Ito’s description of “HAMLET” as a “barrack” seems surprisingly apt. While the word “barrack” has various connotations, its original meaning is “a temporary barracks set up on a battlefield,” meaning that in terms of its temporary nature, it is similar to “Takashimacho Gate.” The construction method proposed for “Oura Town Hall” is also almost temporary, using 50mm square pipes.

After the bubble burst, there was a demand for relentless low-cost and shorter construction periods. The refinement of Yamamoto Riken’s “barrack” architecture was in perfect sync with the times. For Riken Yamamoto, his consistent theme is “When Systems Transform into Expression” (GA Japan 76, September/October 2005).

Institutions, Facilities, and Spaces as Hypotheses

“Architecture is built on hypotheses” (Contemporary Social Conditions 1: Color and Desire (1996)), says Riken Yamamoto. While questions like “Postmodernism, Modernism, or Deconstructivism” may be hot topics in the culture sections of newspapers, for the average person, they are far removed from their everyday lives. Architects are “all about form, with no thought given to content,” while many people believe “form doesn’t matter; content is what’s important.” However, Riken Yamamoto radically asks, “What is the ‘content’ of architecture?”

It’s merely a hypothesis, isn’t it?

“Architecture is built in accordance with institutions. Architecture is a faithful reflection of institutions. It’s now common knowledge for many of us that our surroundings, including not just individual buildings but our immediate surroundings as well as the urban environment, are, so to speak, institutions themselves.” (“Is Architecture an Isolation Facility?” Shinkenchiku, February 1997). I’m reminded of Miyauchi Yasushi’s observation that “today’s urban landscapes can be seen as an almost exact self-expression of the Building Standards Act and the City Planning Act.” (“The City as Landscape – Tokyo 1975,” Shoot the Landscape – University 1970-75: Miyauchi Yasushi’s Architectural Essays (1976)).

Belonging to an “architectural planning” laboratory that focused on the design and planning of public buildings, I was inevitably forced to consider the problems of basing design and planning methods on surveys of spaces that already exist as institutions = facilities. One such essay is “Institutions and Space: A Study of Prefabricated Housing Culture” (Visible Houses and Invisible Houses, Culture Today Series 3, Iwanami Shoten, 1991). For example, with regard to educational facilities, what exactly has postwar “architectural planning” done in the face of the emergence of “open schools” that tout “non-grading” and “team teaching”? Essential reading includes I. Illich’s “Disschooling Society,” M. Foucault’s “The Birth of Clinical Medicine” and “The Birth of the Prison,” and J. Habermas’s “The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere.”

Yamamoto Riken’s “Architecture is Built on Hypotheses” is a very persuasive critique of “architectural planning.” Moreover, as if to encourage architects, he asserts that the common sense that institutions = space is a “hypothesis.” He then goes on to say that “institutions are not that strong.” “If architecture is merely a simple reflection of institutions, then architectural designers are like mere automatic writing machines that transform institutions into spaces. They are translators who translate institutions into space.” (“Is Architecture an Isolation Facility?”)

Architectural Types Specific to Local Communities

As mentioned above, Riken Yamamoto’s design method is preliminarily applicable to all familiar spaces, and as we have already seen, to cities. Rather, the very creation and organization of space—that is, the very establishment of an architectural program—is the starting point.

Modern facilities “were only recently developed as a single building type, during Japan’s development as a modern nation.” It was only after the war that “they were reorganized from the national system into everyday life and relationships with local communities.” “Architecture was the device for expanding the idea of moving from the national system to local communities.”

This is a truly accurate assessment of the situation.

Currently, Japanese local communities are in a critical situation. “Depopulated villages” where children cannot play outdoors are appearing everywhere. The collapse of local communities is inevitable. The nature of public and community facilities is also undergoing major upheaval. With the arrival of an aging society with a declining birthrate, the failure of the existing facility system and spatial organization is becoming clear to everyone. With a surplus of educational facilities such as elementary and junior high schools, it is only natural that there will be an increased need for facilities for the elderly. In addition, there are municipal mergers. Yamamoto Riken has foreseen these issues at a much deeper level.

It must be said that it was too late when the Architectural Institute of Japan’s Architectural Planning Committee – of which I served as chairman from 2006 to 2010 – held a design competition (2008) entitled “Planning Techniques for the Reorganization and Renewal of Public Facilities,” but the fact that it has become clear that various attempts have already been made demonstrates the pioneering and orthodox approach of Yamamoto Riken as an architect.

This was further evidence.

Yamamoto Riken stated, “We need to seriously consider building types that are unique to each local community.” It is clear that “the problem is uniform local communities across the country, and the resulting uniform building types across Japan.” The horizon that Yamamoto Riken reached was the “Community Region Model” (Yamamoto Riken, Nakamura Hiroshi, Fujimura Ryuji, and Hasegawa Go, 2010).

Thinking while building, creating while using

How can we discover or invent new building types? The starting point is the field. The question here is how to assemble them from the field. The purpose of urban tissue (urban tissue/urban fabric) research, or “tipologia” research, in Asian cities is to discover “regionally unique” urban tissues and “architectural typologies.”

Yamamoto Riken’s book is titled “Thinking While Making, Making While Using” (Yamamoto Riken + Yamamoto Riken Design Factory, 2003). It reminds me of Uchida Yoshiya’s “Building and Thinking” (1986), but there’s a new phase in “thinking while making” and “making while using.” He also says, “The process is already architecture.”

Prototype or process? What is the difference between the phase and development of the presentation of “prototypes” such as “The Residence Above a Multi-Tenant Building,” “The House in Okayama,” and “Hotakubo Housing Complex”?

“Thinking While Making/Making While Using” is a unique book that directly documents the process. It describes parts of the design processes for projects such as “Oura Town Hall,” “Future University Hakodate,” “Yokosuka Museum of Art,” and “Shinonome Canal Court CODAN.” In a candid exchange with the staff, he said the following:

“It seems that 20th-century architects always aimed for prototypes. Dominoes, universals. They thought of prototypes as spaces. … If there were no prototypes, the question would be how to make decisions on a case-by-case basis. … At that point, I think there’s a chance for the people directly involved in the architecture to appear, even if I’m not sure if it’s appropriate to call them residents. … Isn’t the word ‘residents’ questionable? ‘Residents’ is such an abstract term that it’s hard to know who they are. …”

Here again, Yamamoto Riken is principled.

The rationalization of the design process and making the decision-making process as open as possible were themes early on proposed by C. Alexander (1936-2022). However, the design process is not that simple. The countless elements that make up a building are broken down using mathematical techniques, and the spatialized parts are then reverse-integrated based on classified given conditions. However, feedback occurs when conditions change or are added. C. Alexander was also aware of this limitation, and compiled a dictionary of basic patterns (details, space, their arrangement, etc.) (pattern book, collection of design materials, model space, etc.) and presented a system in which users (construction entities) could select from them. This was “Pattern Language: A Guide to Environmental Design (Towns, Buildings, Construction)” (1984). Yamamoto Riken critically summarized this “pattern language” theory, noting that C. Alexander’s patterns were assumed to be too universal.

In the design and planning of public buildings or urban development, the “workshop” method is increasingly being attempted as a method of “resident participation.” But who is the entity that determines the system? Yamamoto Riken has repeatedly questioned “subjectivity” (“The Subjectivity of the Planners is Being Questioned,” Architectural Culture, June 1996; “Notes on Subjectivity,” Shinkenchiku, November 1999; “Notes on Subjectivity 2,” Shinkenchiku, September 2000). Serious thought has been poured into the design of “pure space” and “living space,” “physical sensation” and “common sense,” “individual work” and “collaborative work,” “space that resonates,” and more.

The “Oura Town Hall” competition (chaired by judging committee chair Hara Hiroshi) concretely challenged and confirmed the idea that “architecture is the process.” Making the entire process open was groundbreaking. Furthermore, the application requirements and evaluation criteria—”The proposal must incorporate a system that can accommodate the diverse views of others,” and “The realization of architecture induced by the system must be supported by some kind of new aesthetic”—were themes that Yamamoto Riken has been pondering ever since.

Creating the future

Prototype? Process? Who decides what?

I will leave the unfortunate circumstances surrounding the Oura Town Hall project to reports such as those from a symposium held by the Architectural Institute of Japan on March 16, 2007 (“Activity Report: Public Works and Designer Selection – Focusing on the ‘Oura Town Hall Designer Selection Competition with Citizen Participation’,” Architecture Magazine (June 2007)). Also, Yamamoto Riken himself provides a summary of the circumstances and outlines the project in his book Spaces of Power/Power in Space: Designing the Gap Between the Individual and the State (2015) (“4. Architectural Design with Citizen Participation, and the Opponents,” “Chapter 5. ‘Local Power’ Against ‘Electoral Autocracy’”).

While this is generally referred to as “resident participation,” there are significant barriers to the institutional framework surrounding decision-making. The problem lies in the social system (laws and institutions) that supports a system that constantly generates new forms.

However, a “system that constantly generates new forms” can be problematized on a different level. As for who should propose such a system, Yamamoto Riken’s answer is clear: it is the “architect” who can propose it. An “architect” is not simply a “mediator.”

Yamamoto Riken’s eyes began to turn to the entire Japanese architectural world, the entire architectural social system, and Japan’s urban landscape as a whole. From 2007 to 2008, Yamamoto Riken served as chair of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism’s “Guidelines for the Formation of Architectural and Urban Landscapes” Review Committee (Yamamoto Riken, Nuno Shuji, Okabe Akiko, Kinoshita Yoko, Kudo Kazumi, Muneta Yoshifumi, Shitomi Takeo, and Aramaki Sumita). I was familiar with the “town architect (community architect)” theory (Nuno Shuji, “The Naked Architect…An Introduction to Town Architect Theory,” 2000), and I was invited to serve on the committee. In fact, the two of us were involved in its prehistory, going back more than a decade. The main topic of discussion at this time was the introduction of a Japanese version of the CABE design review system. The Director-General of the Housing Bureau was Hiroto Izumi (1953–present). (He served as Director-General of the Housing Bureau of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism in 2007, Director-General of the Integrated Secretariat for Regional Revitalization in 2009, Special Advisor to the Cabinet Secretariat (for National Strategy) in 2012, Special Advisor to the Prime Minister Abe in 2013, Special Advisor to the Prime Minister Kan in 2020, Advisor to the Building Center of Japan, Special Advisor to the Japan Housing Industry Federation in 2021, and Special Advisor to Osaka Prefecture and Osaka City in 2022.) While I will omit the details, this plan never came to fruition due to the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Urban Architect System

Approximately 10 years before the idea of introducing a Japanese version of CABE, the Housing Bureau of the Ministry of Construction conceived the “Urban Architect System.” I have detailed this in “The Naked Architect…An Introduction to Town Architect Theory,” but its origins lie in the “Architectural Culture and Landscape Issues Study Group” (1992-95). A forum was created within the Architectural Technology Education and Promotion Center (established in 1982) where several “architects” and Ministry of Construction staff seconded to prefectures and designated cities as heads of the architectural division (heads of the housing division) could discuss primarily “landscape issues.” The committee members were young bureaucrats from the Ministry of Construction seconded to prefectures and designated cities as heads of the Architecture Division (heads of the Housing Division), architects (Motokura Makoto, Yamamoto Riken, Ashihara Taro, Kuma Kengo, Dan Norihiko, Hirakura Naoko, Takahashi Akiko, Hara Hisashi, Kojima Kazuhiro, Suzuki Edward), and academic experts (Nishimura Yukio (1952-) (Dean of the Faculty of Tourism and Urban Planning at Kokugakuin University, former Vice President and Director of the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology at the University of Tokyo), Onishi Takashi (1948-) (Professor Emeritus at the University of Tokyo, former President of the Science Council of Japan), and in retrospect, it was a distinguished group. The masterminds behind this were Umeno Shoichiro, Director-General of the Housing Bureau at the Ministry of Construction, and Mori Tamio (1949-), a construction specialist in the Construction Guidance Division. Mori Tamio later served as Mayor of Nagaoka for five terms. He served as chairman of the National Association of City Mayors (1999-2016) and as chairman of the National Association of City Mayors (2009-2017).

The issue that sparked his involvement was the problem of illegal buildings. The Ministry of Construction (MLIT) was concerned that the building administration was merely a “policing administration” under the banner of compliance with the Building Standards Act and was not contributing to the creation of orderly cityscapes. The study group engaged in extensive discussions in response to the issues raised by the participating members and traveled to various locations to hold symposiums and lectures.

The study group’s conclusion was that “the creation of rich cityscapes requires the continued participation of architects and a new system is needed.” The initial concerns were how to create excellent cityscapes, how the building administration can guide landscape formation, and what kind of system to create for this. The idea of incorporating architects into this system came to be known as the “urban architect” system. However, this idea was never realized due to the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake.

IV. Spaces of Power/Power in Space: Toward the Formation of a Regional Community Sphere

Yamamoto Riken serialized his essay titled “Designing the Space Between the Individual and the State” in the magazine Shiso (Iwanami Shoten) in five installments in 2014, and collected and published it as Spaces of Power/Power in Space in 2015. While the work originated from a blog for the Yamamoto Riken Studio at Y-GSA, establishing a base in Yokohama allowed him to summarise his previous thinking in a more cutting-edge way. One reason for this was his involvement in the friction with local governments and residents surrounding the Oura Town Hall (2002–2009), Odawara City Civic Hall (2005), and Amakusa City Hall (2015). Another reason was his full engagement with the thought and writings of Hannah Arendt (1906–1975).

No Man’s Land

“Spaces of Power/Power in Space” is transcribed as follows: “There is a mysterious passage in Hannah Arendt’s book The Human Condition (1958).” (1. What is “no man’s land”? Chapter 1: The spatial concept of “threshold.”) The passage, as outlined in Masahiko Makino’s new translation (Kodansha Academic Library, 2023), is from “Chapter 2: Public and Private Spheres,” “8. Private Sphere – Property,” which reads: “For the city, the interior sphere of the home remains hidden and has no public significance whatsoever, but the part that appears on the outside has important significance for the city. It appears within the public sphere in the form of a boundary that distinguishes one home from another. Law originally referred to this boundary line. In ancient times, law was an actual space, a kind of no-man’s land between the private and the public, which protected both public and private spheres while simultaneously separating them.” Using Arendt’s discussion of the “public sphere,” “private sphere,” “borders,” “law,” and “no man’s land” in this passage, Yamamoto Riken reinforces his “threshold theory.” The gist of his argument is that a “threshold” is a space like a “no man’s land,” “a space that exists between two different spheres, connecting or separating their mutual relationships,” “the space between the public sphere of the city and the private sphere of the family is a ‘threshold’,” and “a ‘threshold’ is an architectural device that ‘connects and separates’ the people who live there at the same time.”

The above will also be the gist of his Pritzker Prize commemorative lecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology, “A Theory of Community Based on the Concept of Threshold” (May 16, 2024), and his special lecture “Threshold Theory” (June 7, 2024) to commemorate his 2024 Pritzker Prize, Professor Emeritus, and Honorary Doctorate at Yokohama National University. “

Labor, Work, and Action

Yamamoto Riken’s interpretation of Hannah Arendt’s thought, of course, goes beyond merely reinforcing her “limbic theory.” Following her magnum opus, The Origins of Totalitarianism, The Human Condition, which positions Arendt’s philosophy within the context of Western philosophy beginning with ancient Greece, resonates deeply with her thought.

The Human Condition does not address philosophical questions such as “What is humanity?” or “What is the world?” Its central theme is “What exactly is it that we are doing?”—”vita aciva” as the “human condition.”

Arendt divides human activity into three categories: labor, work, and action, and examines each as part of the “human condition.”

Labor corresponds to the biological processes of the human body. The process of natural human growth, absorbing and metabolizing substances from the outside world, and eventually decaying and dying is constrained by the necessities of life. These necessities of life must be produced through labor and incorporated into the life process. Therefore, the human condition for the activity of work is life itself.

Work is an activity that corresponds to the non-natural aspect of human existence. Work creates a world of “artificial” objects that is clearly distinguished from all natural environments surrounding humans. The world itself continues even after the death of individual humans, and in that sense, must exist beyond all individuals. The human condition for the activity of work is the existence of a world distinct from nature.

Action is the only activity that takes place directly between humans, without the intervention of objects. The condition for the activity of action lies in the fact that multiple humans, not a single abstract human being, live on this earth and inhabit the world.

All three conditions—labor, work, and action—are linked to politics, but Arendt argues that plurality—”to live” is “being among people”—is an “essential condition” for politics and a “sufficient condition” for its existence.

Architects work to create a world of “artificial” objects that will continue to exist even after human death. Drawing on Arendt, Yamamoto Riken explores the meaning of work (“2. The Worldliness of Work,” Chapter 3: The Space of “Society” that Preys on the Space of “World”).

Electoral Despotism

As an architect whose “work” involves creating “things” and “spaces” in the world, Yamamoto Riken’s encounters with the Oura Town Hall (2002-2009), Odawara Civic Hall (2005), and Amakusa City Hall (2015), as well as his dismissal as president of Nagoya Zokei University (2018-present) (2021), demonstrate the deterioration not only of Japan’s architectural world today but of Japanese society as a whole.

Having been unjustly deprived of his work opportunities, it is only natural that he would be so vocal in his criticism of “electoral despotism,” “standardization,” and “bureaucratic management.” However, this analysis is dispassionate.

The contract for the Odawara Civic Hall (2009) was cancelled just as the detailed design was being completed and the bidding process was about to begin to decide on a construction company. Leading the charge in opposition was the Komatsuza troupe, led by playwright Inoue Hisashi.

The Civic Hall, tentatively titled “Castle Town Hall,” was originally designed to be a multi-purpose hall, and a design competition was held. Yamamoto Riken Design Factory proposed “a hall that the citizens of Odawara City could use at their own discretion,” describing it as “a hall that could be used for professional wrestling events and circuses. Of course, it would have sufficient architectural capabilities as a theatrical space or for concerts. It would also be a multi-purpose hall that could be used by junior high school students and children. Had it been realized, there’s no doubt it would have been a unique hall.

However, Inoue Hisashi intervened, saying, “The idea of a multi-purpose hall is poor. It will inevitably degenerate into a purposeless hall” (“Why build it here now (Participating in History),” Shinsei Minpo). “Komatsuza has covered theaters all over the world, and we believe we know more about theaters than anyone in Japan,” he says, adding, “All the world’s best theaters have a seemingly ordinary form (which lies in the essence of theater). The only thing that’s okay to be strange is the program.”

It’s true that there are many cases where a “multipurpose hall” is not used for multiple purposes and “degenerates into a purposeless hall” if the hall is not actively managed. However, it’s all a matter of the program of the builder (local government) and the review committee, and it’s the “seemingly ordinary form” that should be questioned – the essence of theater. Moreover, Odawara City’s required standard was a “multipurpose hall,” not a “dedicated theater.”

Yamamoto Riken responds, “Only those who think about theater are qualified to create something unusual (something new and unprecedented). Knowledge belongs to the ‘thinker.’ Those who implement it (those who create architecture) should follow that knowledge. In reality, each theater around the world is unique to its local community. They are by no means ordinary or standard. There is a hidden discrimination against those who create things, and this is not limited to architecture. There are ‘thinkers.’ There are ‘people who create things’ in accordance with those ideas; this is the ‘Platonic separation between knowledge and action’ (Arendt)” (Afterword to “Power Spaces/Power in Spaces”).

In the end, Odawara Civic Hall (commonly known as Odawara Sannomaru Hall) was completed in 2021, the designer was changed to Mitsuru Senda (1941- ) (former president of the Architectural Institute of Japan and former president of the Japan Association of Architects), and the builder was Kajima Corporation. Was the “seemingly ordinary form” that Inoue Hisashi spoke of, the essence of theater, realized?

In the case of the Amakusa City Hall, the architectural design work was done by the Yamamoto Riken Design Factory JV (Yamamoto Riken Design Factory, IGA Architects, Hirota Architects & Urban Design Studio, Fujimoto Miyuki Design Office), but the outcome was unclear at the time of the publication of “Spaces of Power/Power in Space.” In order to participate in the “Kumamoto Artpolis,” Amakusa City held an open proposal competition for the construction of the city hall in June 2013 and selected the Yamamoto Riken Design Factory JV as the designer. However, the new mayor elected in March of the following year withdrew from the “Artpolis Project” and terminated the contract. A lawsuit seeking payment of unpaid design fees following the termination of the contract was settled in 2020.