Tokyo Becoming Colony for the Rich, Pritzker Winner Warns

Riken Yamamoto says massive projects are “destroying the heart” of the city.

By Sarah Hilton

January 21, 2026 at 8:00 AM GMT+9

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/11ehKSeDWkR2KDfso-wFAW2hXbeA_PUsp?usp=drive_link

Tokyo Becoming Colony for the Rich, Pritzker Winner Warns

Riken Yamamoto says massive projects are “destroying the heart” of the city.

By Sarah Hilton

January 21, 2026 at 8:00 AM GMT+9

An award-winning architect warned that Tokyo is being trampled by luxur developments, issuing a rare rebuke of his peers for catering to wealthy interests over the public.

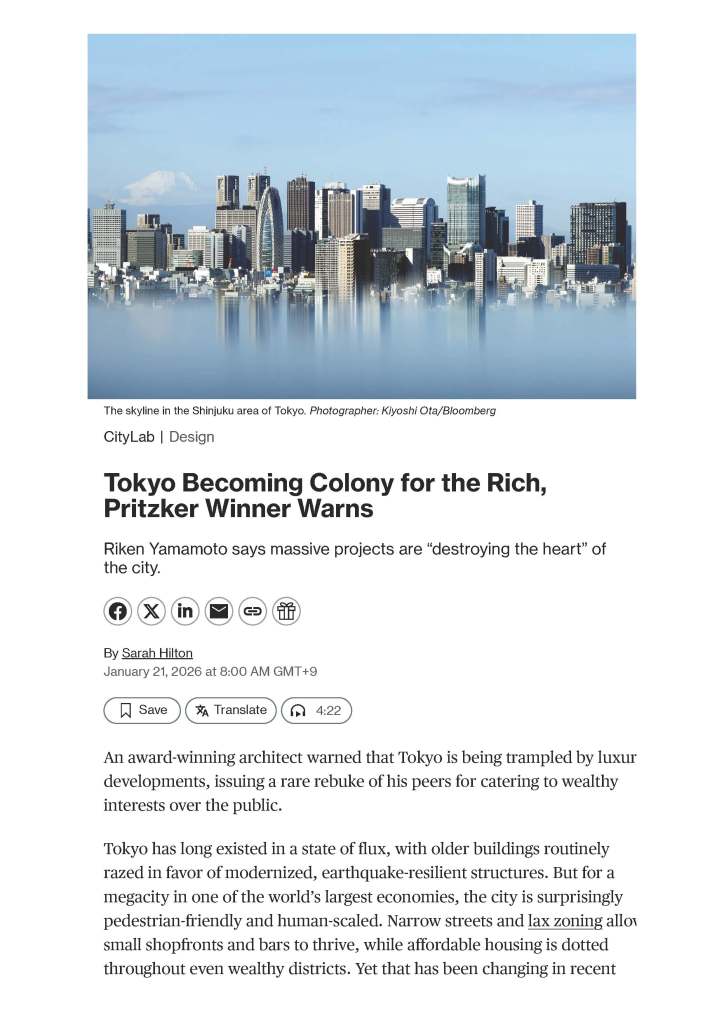

Tokyo has long existed in a state of flux, with older buildings routinely razed in favor of modernized, earthquake-resilient structures. But for a megacity in one of the world’s largest economies, the city is surprisingly pedestrian-friendly and human-scaled. Narrow streets and lax zoning allo small shopfronts and bars to thrive, while affordable housing is dotted throughout even wealthy districts. Yet that has been changing in recent

years, with sculptural glass-and-steel buildings filled with boutiques, office and luxury condominiums springing up throughout the city.

“This is like a colony by rich people, ‘neoliberalism’ people,” said Riken Yamamoto, recipient of the 2024 Pritzker Prize — often called the Nobel Prize of architecture — during a recent talk at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan. “What is being built is completely unusable by people in th community.”

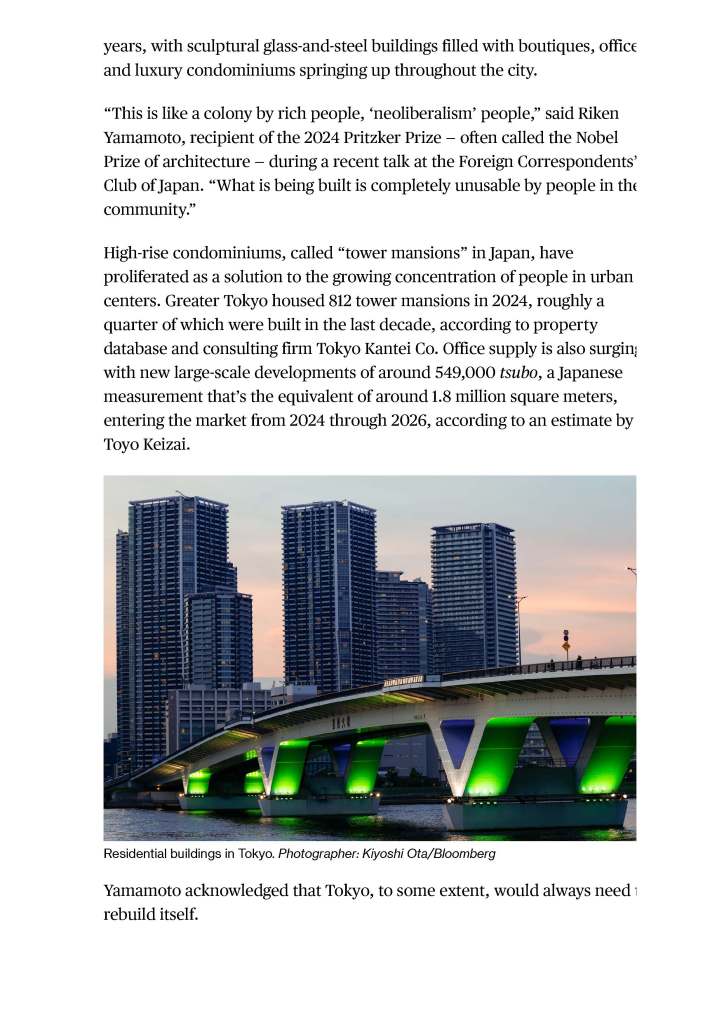

High-rise condominiums, called “tower mansions” in Japan, have proliferated as a solution to the growing concentration of people in urban centers. Greater Tokyo housed 812 tower mansions in 2024, roughly a quarter of which were built in the last decade, according to property database and consulting firm Tokyo Kantei Co. Office supply is also surgin with new large-scale developments of around 549,000 tsubo, a Japanese measurement that’s the equivalent of around 1.8 million square meters, entering the market from 2024 through 2026, according to an estimate by Toyo Keizai.

Residential buildings in Tokyo. Photographer: Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg

Yamamoto acknowledged that Tokyo, to some extent, would always need rebuild itself.

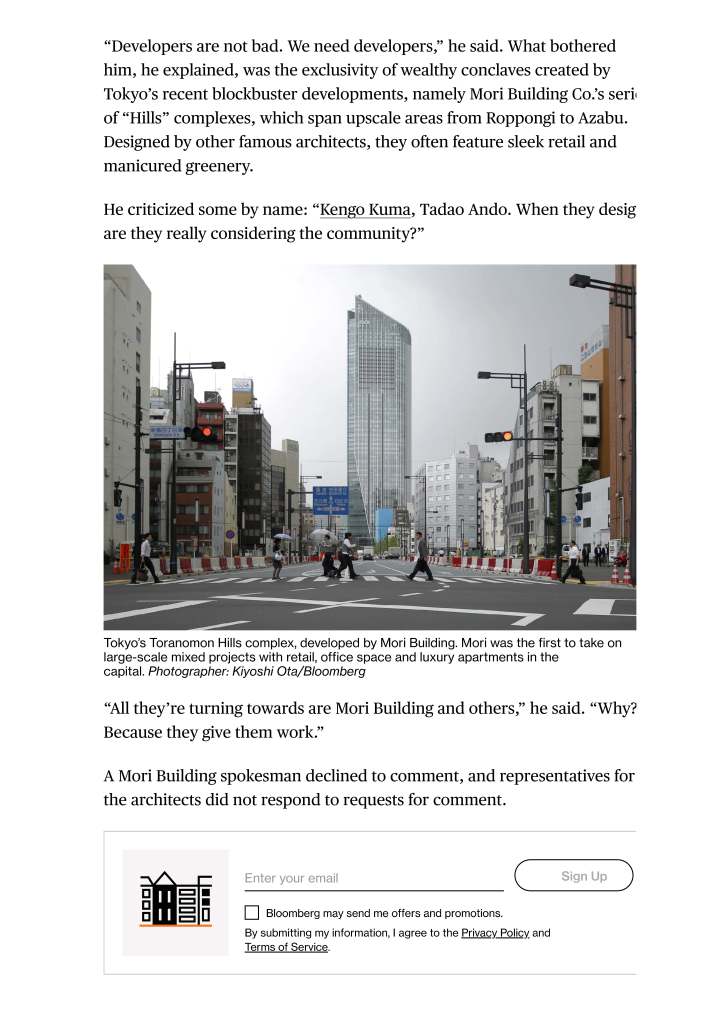

“Developers are not bad. We need developers,” he said. What bothered him, he explained, was the exclusivity of wealthy conclaves created by Tokyo’s recent blockbuster developments, namely Mori Building Co.’s seri of “Hills” complexes, which span upscale areas from Roppongi to Azabu. Designed by other famous architects, they often feature sleek retail and manicured greenery.

He criticized some by name: “Keng o Kuma, Tadao Ando. When they desig are they really considering the community?”

Tokyo’s Toranomon Hills complex, developed by Mori Building. Mori was the first to take on large-scale mixed projects with retail, office space and luxury apartments in the

capital. Photographer: Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg

“All they’re turning towards are Mori Building and others,” he said. “Why? Because they give them work.”

A Mori Building spokesman declined to comment, and representatives for the architects did not respond to requests for comment.

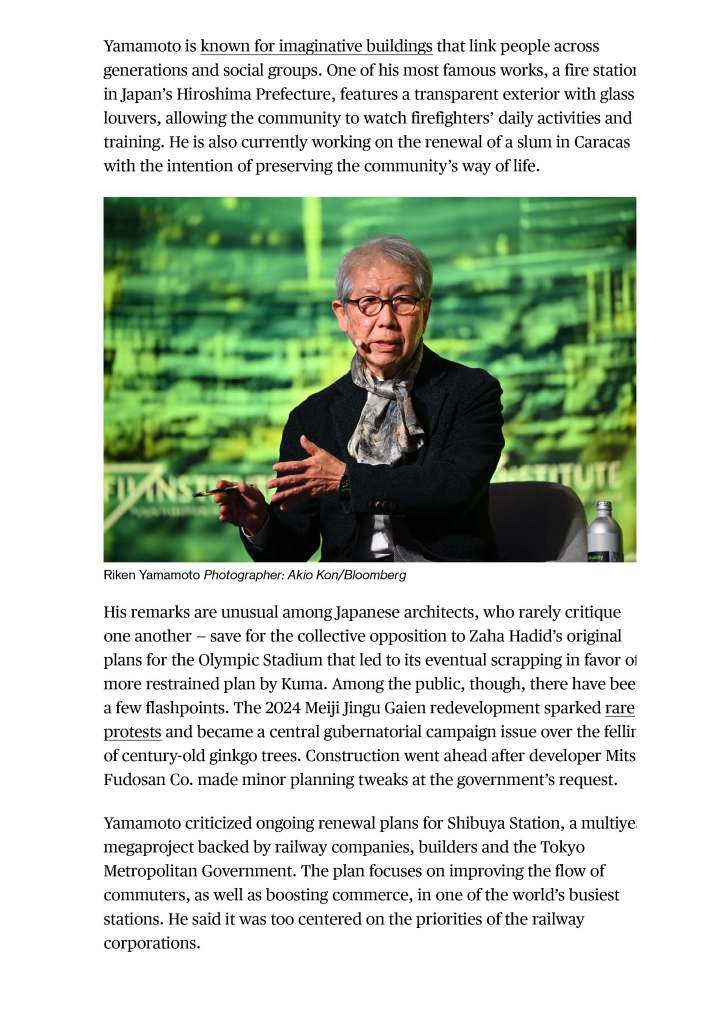

Yamamoto is known for imaginative building s that link people across generations and social groups. One of his most famous works, a fire statio in Japan’s Hiroshima Prefecture, features a transparent exterior with glass louvers, allowing the community to watch firefighters’ daily activities and training. He is also currently working on the renewal of a slum in Caracas with the intention of preserving the community’s way of life.

Riken Yamamoto Photographer: Akio Kon/Bloomberg

His remarks are unusual among Japanese architects, who rarely critique one another — save for the collective opposition to Zaha Hadid’s original plans for the Olympic Stadium that led to its eventual scrapping in favor o more restrained plan by Kuma. Among the public, though, there have bee a few flashpoints. The 2024 Meiji Jingu Gaien redevelopment sparked rare protests and became a central gubernatorial campaign issue over the fellin of century-old ginkgo trees. Construction went ahead after developer Mits Fudosan Co. made minor planning tweaks at the government’s request.

Yamamoto criticized ongoing renewal plans for Shibuya Station, a multiye megaproject backed by railway companies, builders and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. The plan focuses on improving the flow of commuters, as well as boosting commerce, in one of the world’s busiest stations. He said it was too centered on the priorities of the railway corporations.

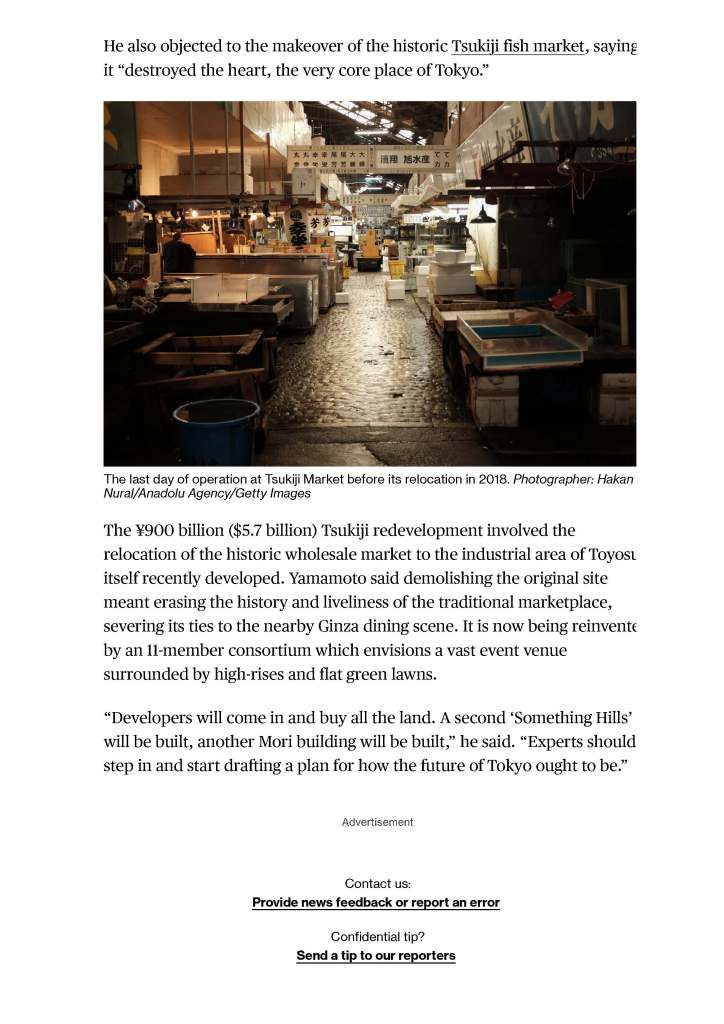

He also objected to the makeover of the historic Tsukiji fish market, saying it “destroyed the heart, the very core place of Tokyo.”

The last day of operation at Tsukiji Market before its relocation in 2018. Photographer: Hakan Nural/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

The ¥900 billion ($5.7 billion) Tsukiji redevelopment involved the relocation of the historic wholesale market to the industrial area of Toyosu itself recently developed. Yamamoto said demolishing the original site meant erasing the history and liveliness of the traditional marketplace, severing its ties to the nearby Ginza dining scene. It is now being reinvente by an 11-member consortium which envisions a vast event venue surrounded by high-rises and flat green lawns.

“Developers will come in and buy all the land. A second ‘Something Hills’ will be built, another Mori building will be built,” he said. “Experts should step in and start drafting a plan for how the future of Tokyo ought to be.”

Leave a comment