Memory and Silence in Japan

How do Japanese artists respond to Japanese recent past?

Akiko Tanio(Funo)

Commentary by Shuji Funo

The author, who had been suffering from an incurable disease of unknown cause called idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, had been waiting for a lung transplant since July 1919. However, he never received that opportunity, and after suffering from several pneumothoraxes, passed away (December 5th). Having just turned 40, his final words were, “It’s hard to breathe, so I want to sleep like this and wake up in two years and be alive.”

While sorting through the author’s writings, I reread his master’s thesis (art history) submitted to Goldsmiths, University of London, and was impressed by its vivid awareness of the issues and its incredibly logical construction. I was particularly struck by the concept of postmemory. The original was in the form of an essay without headings or notes, but I decided to translate it, hoping to reach as many people as possible, and quickly compiled it into a booklet, along with the English translation. I also sent it to Yamamoto Riken, a friend of mine from our youth, and it was published in the inaugural issue of this magazine. This was an unexpected development, and I believe the late poet would be very pleased.

This paper has great scope and depth. What needs to be explored in post-memory theory in Japan is the “memory and silence” of World War II. It is surprising that this paper was proposed in 2003. As a translator, I would like to seriously consider Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Fukushima, the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (imagined community and community), architecture, and more.

Introduction

Although it has been only two years since it turned to the 21st century, the world has been disquieting. There have been the incidents such as the terrorist attack on the U.S., War on terrorism, War on Iraq and the conflict between Palestine and Israel among many. These incidents make me think about wars in the 20th century in Japan. Japan has come to today without dealing with the recent past. The oblivion of this past seems to be a big issue. Postmemory as a site of remembrance seems to be limited in Japan, for the memory of the past has been repressed, and the history has been concealed. Memory is ambiguous, but it seems that History is also ambiguous in a different way, for the authority have the power to control it. The authority has manipulated the silence. Japanese memory of the War has been silenced in various ways to turn our eyes away from the sense of guilt. Japanese atrocities have remained silence in teaching history. Japan has also remained silence about the responsibility of the emperor for the war.

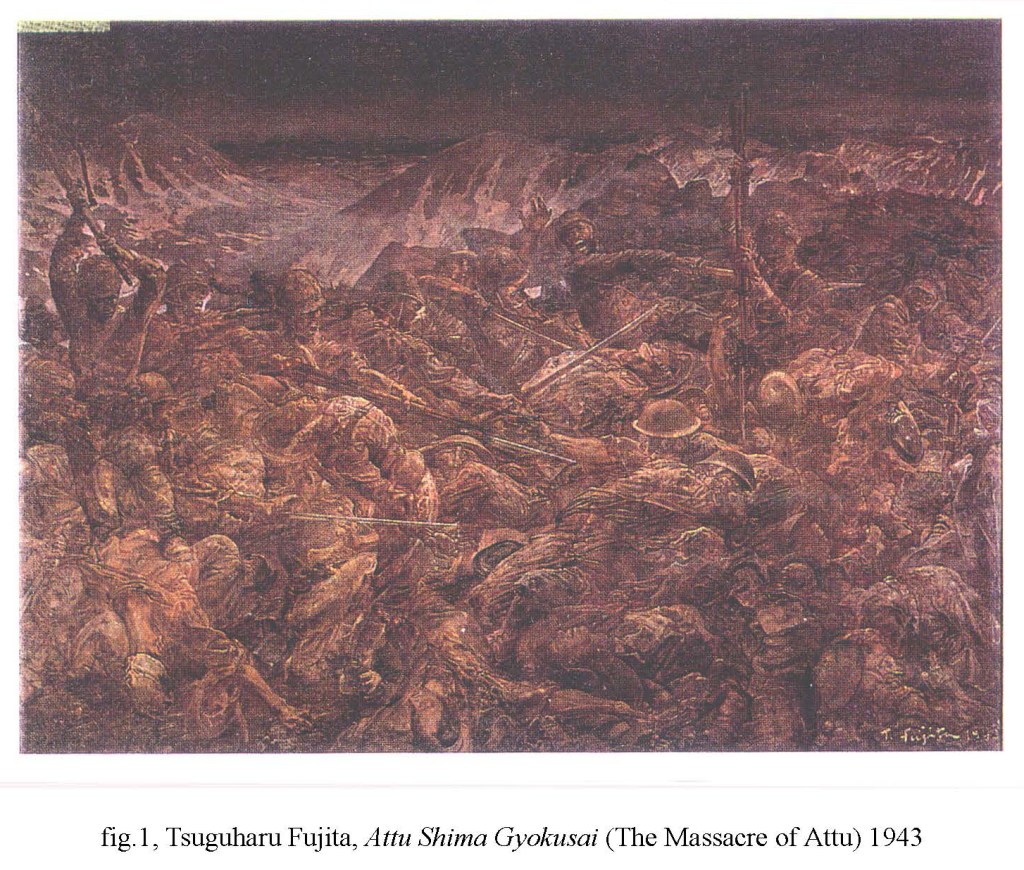

In the art world, war paintings were also hidden from the public after the War. It is only recently that the war paintings became open to the public more often than before, and the re-examination of the war paintings began. Tsuguharu Fujita, who actively produced war paintings, left or was forced to leave Japan in 1949. Silence as a tool for authorities was imposed not only within, but also from outside Japan. The U.S. censorship delayed the publication of Genbaku Bungaku (A-Bomb literature).

However, ‘silencing’ is only one aspect of silence. It is true that silence can well be the hindrance of postmemory, but at the same time, I think that postmemory can be practiced through the silence. Like memory, silence is ambiguous because of its duplicity. Silence is the opposite of language as well as a part of language. Silence makes people imagine what is veiled and what is buried. Moreover, I would like to suggest that silence might have the ability to hold the past in the present.

Thus, I would like to consider other notions of silence that contains the unsaid and the unspeakability. Postmemory also implies the unrepresentability. It implies the distance between the self and the other – postmemory as Matrix in which the self and the other coexist without fusion.

The works or art practices that deal with Japanese recent past seem to approach to the silence in various ways. Some artists usually do not deal with the War, other artists primarily focus on the War. Many artists deal with Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Tadashi Tonoshiki (born in 1942) was an artist who actually experienced the nuclear bomb in Hiroshima. He started to produce works from his recollections of the explosion after twenty years of silence. Shomei Tomatsu (born in 1930) keeps taking photographs of the survivors of the past, particularly the survivors of Nagasaki. Tomatsu’s photographs draw attention to counter-history. Tatsuo Miyajima (born in 1957), is also an artist who was haunted by the nuclear bomb dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Since 1995, Miyajima started a project ‘Revive Time Kaki Tree Project’. It responds to a fading memory. The works of Masao Okabe (born in 1942) focus on activating the memory of the past. His works leave the trace not to lose the memory of the war along with the loss of the remains. Takashi Murakami (born in 1962) is probably the most famous Japanese contemporary artist in the West as well as in Japan. Recently, he has exhibited a wall painting Time Bokan (1999). This seems to question the representation of the nuclear bomb.

There are some art practices that touch upon the hidden part of the official history and try to break the silence. Yukinori Yanagi and Yoshiko Shimada both touch upon Japanese unpleasant, hidden or repressed histories. Shimada uncovers the repressed histories within her works, whereas Yanagi focuses on the obscurity of the silence in contemporary Japan. The young artist Makoto Aida (born in 1965) produced a series called Sensoga Returns (War painting returns) from 1995 to 1996 in which he draws attention to the relationship between the present and the past.

I would like to discuss how this recent past is repressed and silenced by considering the notion of memory, history, postmemory and silence. Then I would like to discuss art works or art practices that deal with Japanese recent past, namely World War II.

History

Talking about the recent past is difficult especially for Japan which was defeated in World War II, but at the same time, it is crucial for Japan in which memory of the War seems to be fading. Various atrocities were taken place in this War, and each genocidal act cannot be compared to each other. Furthermore, as Dominick LaCapra points out, subject position restricts the discourse of this past. LaCapra argues in the context of Holocaust that ‘[w]hether the historian or analyst is a survivor, a relative of survivors, a former Nazi, a former collaborator, a relative of former Nazis or collaborators, a younger Jew or German distanced from more immediate contact with survival, participation, or collaboration, or relative “outsider” to these problems will make a difference even in the meaning of statements that may be formally identical (in Friedlander, 1992: 110). I think that it could fit in the case of Japan, or maybe in any case. In the case of Japan, whether those who went to the War, or those who did not participate in the actual battle even though they were in the military, a survivor of Hiroshima or Nagasaki, a relative of survivors, younger generation who did not experience the War will make a difference. I would like to reflect Japanese recent past from my subjective position as a Japanese, as one who has never experienced the war, and as one whose parents were born after the Second World War.

I was eleven years old when I learned Japanese history for the first time as far as I am concerned. Since then, I had several occasions to learn both Japanese and the world history, but I have never learned much about Japanese recent history, namely history of the twentieth century. What I remember the most in Japanese history is primitive era. Teachers always laid weight on history of primitive era, and there was no time for history of the twentieth century in the end of the year. The next year, it was the same. It was all again the repetition of a year before starting from the primitive era. I might be exaggerating this, but I am writing from my memory that I remember many things about primitive era, but my knowledge of recent history is limited.

However still, I feel the fear of forgetting Japanese recent past, Japanese history, atomic bomb dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I feel the fear of Japanese people forgetting them. It is because, I think, I have a memory of absence. I mean that I have a memory that I did not learn much about Japanese history although I know that there are many things that are glossed over. Memory is so fundamental to our lives. Without memory, we can neither remember nor forget. It ‘acts in the present to represent the past’ (Antze and Lambek, 1996: xxiv).

However, it is true that memory is ambiguous. It is always already selected. ‘Memories are produced out of experience and, in turn, reshape it’ (ibid: xii). Thus it occupies the site between the happened and the imagined. This does not mean that memory it totally unreliable, for History is always already selected as well. Memory seems more powerful because it is something that the authority cannot take away from us.

As I did not learn much about Japanese recent history, the authority has controlled history. Thus it is not only memory that is ambiguous, but also history is ambiguous. As Jacques Derrida argues, the authority has the power to interpret the archives (1995: 2). ‘The documents, which are not always discursive writings, are only kept and classified under the title of the archive by virtue of a privileged topology. They inhabit this uncommon place, this place of election where law and singularity intersect in privilege’ (ibid.: 3). Trinh T. Min-Ha also argues that ‘the historical analysis is nothing other than the reconstruction and redistribution of a pretended order of things, the interpretation of even transformation of documents given and frozen into monuments. The re-writing of history is therefore an endless task’ (1989: 84). ‘[R]ecording, gathering, sorting, deciphering, analysing and synthesizing, dissecting and articulating are already “imposing a structure”, a structural activity, a structuring of the mind, a whole mentality (ibid.: 141).

History with capital H is his story that indicates the notion of patriarchy. It is constructed based on documents. There is not only one History, however. There are many histories. A historical fact is surrounded by silence, and the silence contains other histories. As Min-Ha argues, ‘[l]iterature and history once were/still are stories: this does not necessarily mean that the space they form is undifferentiated, but that this space can articulate on a different set of principles, one which may be said to stand outside the hierarchical realm of facts’ (ibid.: 121). When story became history, ‘it started indulging in accumulation and facts’ (ibid: 119). We need histories that are always in the process, ‘no end, no middle, no beginning; no start, no stop, no progression; neither backward nor forward, only a stream that flows into another stream’ (ibid.: 123).

Postmemory

Memory of the War is not produced out of my experience. People who did not experience the War can only construct their own memories of the War through others’ memories. Postmemory, according to Marianne Hirsch, is the term which describes ‘the relationship of children of survivors of cultural or collective trauma to the experiences of their parents, experiences that they “remember” only as the stories and images with which they grew up, but that are so powerful, so monumental, as to constitute memories in their own right’ (in Bal et al. (eds.), 1999: 8). Yet, as Hirsch also argues, postmemory is ‘not an identity position, but space of remembrance, more broadly available through cultural and public, and not merely individual and personal acts of remembrance, identification, and projection’ (ibid.: 8-9). It is ‘ a powerful form of memory precisely because its connection to its object or source is mediated not through recollection but through projection, investment, and creation’ (ibid.: 8). However, in the case of Japan, the act of postmemory seems to have been limited.

Japan has come to today without dealing with its own past. The memory of Japanese recent past seems to be under ‘ instances of muteness which by dint of saying nothing, imposed silence’ (Foucault, 1984: 17). The authority has wielded its power to silence and repress memories of the past. Silence is what the authority manipulated. Japanese memory of the War has been silenced in various ways to turn our eyes away from the sense of guilt. As I mentioned above, Japanese atrocities has remained silence in teaching history. Teachers cannot teach the history because of the equivocation of the government. There has been the controversy surrounding a Japanese history textbook that glorifies pre-war Japan and denies atrocities such as the Nanking massacre or the comfort women.

Japan has also remained silence about the responsibility of the emperor for the war. The emperor system is deep-rooted in Japanese society. The emperor had been regarded as a living god until he declared that he was human after the World War II. Furthermore, the structure of the emperor = authority still remains. The emperor system is not a kind of authority that controls overtly nowadays. It is an authority that does not usually appear on the surface. It is regarded as the normative. The power resides within silence, and it remains because of silence. The fact that the emperor Hirohito, who was in charge of the War, did not take the responsibility for the War, and being officially innocent is, I think, one of the reasons that caused Japanese people’s ignorance of history. As Reiko Tachibana argues:

[M]aintaining silence about the emperor’s responsibility for the war enabled Japanese people to deny their own responsibility as well, for Japanese soldiers and citizens who were regarded as the children of the divine emperor believed (or pretended to believe) that they had had no choice but to obey him. During occupation period, when their father-emperor lost his identity, this concept became transferred, and they were temporarily adopted by democratic father and called “MacArthur’s children”. The adopted father’s assertion of their own father’s innocence, along with the Japanese government’s post war propaganda – which now portrayed the emperor as a pacifist – easily convinced them that their father had been betrayed by the military leadership during the war (1998: 10-11).

War Paintings

In the art world, war paintings were also hidden from the public after the War. A number of war paintings were produced as propaganda during the War, especially during Pacific War. The rations of materials such as paint and canvas depended on how much artists cooperate with the military. As war paintings disappeared from the public after World War II, they were erased from post-war Japanese art history. They were not open to public for more than thirty years after World War II. The United States confiscated 153 war paintings as booty just after World War II, and put them into a room of National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. War paintings stayed there for six years, but the Japanese government was certainly uncomfortable with them. The uneasiness of the government increased even more when war paintings were inserted in Winston Churchill’s The Second World War. In July 24th, 1951, suddenly several American military lorries were drawn up to the Museum, and war paintings disappeared. War paintings were taken to the United States, and stayed there for almost twenty years. Although war paintings returned to Japan from the U.S., they were again confined (my translation, Hariu, 1979: 32-34).

Tsuguharu Fujita, who actively produced war paintings, left Japan in 1949. While many artists gave up producing war paintings in the face of the sign of defeat, Fujita kept painting sadistically and frantically, and actually he could not stop painting (my translation, Kikuhata, 1978: 41). ‘The moral issue of artists’ complicity with the military government was quite separate from the war crimes which were punished at the Tokyo Trials and in purges of the civil service’ (Hariu, 1985: 24-25). Fujita was the one to be blamed. In 1947, Iwao Uchida, who also produced war paintings, told Fujita that Fujita ‘had been officially condemned by the Japan Art Association because of his leading role as a war artist’ (ibid: 24). Fujita first went to the United States, and then went to France. Later, he got a French citizenship and also became Christian. He never went back to Japan. As an art critic Ichiro Hariu argues, ‘by using Fujita as a scapegoat many artists were able to expiate their own guilt and to forget entirely the question of their own moral responsibility’ (ibid: 25).

fig.1, Tsuguharu Fujita, Attu Shima Gyokusai (The Massacre of Attu) 1943

Recently, war paintings have begun to be open to the public more often than the past. Furthermore, the reconsideration of war paintings has begun. An art critic Noi Sawaragi argues that ‘what we should find from war paintings is neither to condemn the artists who produced war paintings from the moral point of view, nor to analyse war paintings in terms of form setting aside the value judgement of the subject matter. Rather, we should think about how such practices which enabled to depict such kind of fake justice, aesthetics, history and fear without any doubt, came into existence in the concealment of modernity’ (my translation, 1998: 334).

War paintings eliminated people’s life, people’s struggling, people’s poverty, and brought sublime and heroic historical scenes that were produced out of the ideology. In that sense, Sawaragi uses the term brightness for war paintings and the darkness for people’s life. However, the darkness resides in Fujita’s Attu Shima Gyokusai (The Massacre of Attu) (1943) (fig.1). In an obturated space in which soldiers cannot move at all, the soldiers are jumbled together so that friends and enemies cannot be ascertained. It turns into the hand-to-hand battle, and the soldiers are dissolved. As Sawaragi argues, Attu Shima Gyokusai rather seems to ‘disclose the unfoundedness of justice, history and aesthetics’ because Fujita painted too fanatically. Thus this painting contains the darkness within the brightness. Today Japan has developed economically, and it might look like Japan is a peace country under article nine of its war-renouncing constitution (though the president Koizumi recently decided to send forces to Iraq without a UN mandate). However, Japan, which has stuck the head in the sand, and has concealed the memory of the War under the name of pacifism, might have the same kind of brightness as the wartime that was supported by the ideology. That is to say, contemporary Japan also has the darkness within the brightness. Japan might have been supported by the ideology although it is different from the one in the wartime. The ideology consists of the concealment of the past.

Silence

Silence as a tool for authorities was imposed not only within, but also from outside Japan. It was not only Japanese authority that manipulated silence, but also the United States. Genbaku Bungaku (A-Bomb literature) delayed to be published under the U.S. censorship. For example, Yoko Ota’s City of Corpses (1948) was completed in 1945, but it was censored at that time. It took three years to be published. However, the publisher censored the second chapter, entitled “Expressionless Faces”, (Tachibana, 1998: 44). Ota, in her autobiographical short story, mentions about the interrogation she had with an American officer. He asked her if anyone else or any foreigners have read it. He finished the interrogation saying, ‘I want you to forget your memories of the A-bomb. Since America will never use the A-bomb again, I want you to forget the event of Hiroshima’ (ibid.: 272). Tachibana argues that ‘what may have made [the second] chapter unacceptable to the authorities is not only Ota’s documentation of the effects of the A-bomb, but her assessment that the bomb marked, rather than caused, the end of war’ (ibid.: 44).

Silence that was imposed by the authority had the effect to limit the act of postmemory in Japan to a great extent. As Foucault argues, ‘in order to gain mastery over [the people] in reality, it had first been necessary to subjugate it at the level of language, control its free circulation in speech, expunge it from the things that were said, and extinguish the words that rendered it too visibly present’ (1984: 17). The authority chose to silence or veil the fact as though it could be diminished. Silence here is used as ‘the instrument of the bureaucrat, the demagogue, and the dictator’ (Haidu in Friedlander (ed.), 1992: 278). However, this notion of silence is only one aspect of it. Thus, I think that there is a possibility within silence because silence like memory has got the ambiguity and the fluidity.

As Peter Haidu argues, ‘[s]ilence is the antiworld of speech, and at least as polyvalent, constitutive and fragile…. Silence can be a mere absence of speech; at other times, it is both the negation of speech and a production of meaning’ (ibid.). Silence could imply both yes and no. Silence can be acknowledgement or ignorance. Silence ‘must be judged in its own contexts, in its own situations of enunciation’ (ibid.). Hence, silence has got the duplicity that it is not language, yet a part of language. It is ‘enfolded in its opposite, in language. As such, silence is simultaneously the contrary of language, its contradiction, and an integral part of language. Silence, in this sense, is the necessary discrepancy of language with itself, its constitutive alterity’ (ibid.). Silence ‘neither bound to nor fragmented by time, is ambiguous and suggestive, implicit and connotative’ (Kane, 1984: 19). It seems that silence occupies the space between the said and the unsaid.

In Japan, silence has been utilized as the instrument of the authority, but silence always contains the unsaid, that is, things silenced but still there. The hidden past with ‘complex feelings of indeterminate having happened’ (Lyotard, quoted in Friedlander, 1992: 5) resides in the long silence of Japan. Silence itself is the burden. Some people are afraid of the silence to be broken, and others are waiting for that moment, or trying to break it. I think that the silence has the ability to hold the past in the present rather than to freeze the past into closure. As Jean-François Lyotard argues, there is ‘something which must be able to be put into phrases cannot yet be. This state includes silence, which is negative phrase, but it also calls upon phrases which are in principle possible’ (1988: 13). It is true that silence could be the hindrance of postmemory, but at the same time, I think that postmemory can be practiced through the silence. Thus in the case of Japan, postmemory has been more like ‘experiences that people ‘remember’ only as the ‘silence’ with which they grew up, but that are so powerful, so monumental, as to constitute memories in their own right”. Silence make people imagine what is veiled, what is buried and what is under the water. Memory of silence could produce the fear of not knowing. I would like to think that the quality of silence has got the possibility of the openness, though with a great risk. Because of silence, there are people who try to break the silence with their own memory. For example, three Korean comfort women field a lawsuit against the Japanese government in 1991 after fifty years of silence. ‘The military initially refused to acknowledge responsibility for the system, but once substantial written evidence showed the extent of this highly organized form of sexual slavery, which involved about 139,000 Asian women, politicians were reluctant to compensate the women because they were regarded as prostitutes’ (Lloyd in Lloyd (ed.), 2002: 84).

However, there is a great risk within silence when silence becomes obedient to the authority. Silence allows irrational narratives or discourses to appear such as the revisionist history textbook, which I have mentioned above. In cultural sphere, there is also such kind of tendency. The popularity of Japanese pop culture in Asia is sometimes used as an excuse for ending the memory of Japanese recent past history. It is true that silence caused Japanese people’s ignorance of history. I personally feel that there must be a place where people can learn Japanese recent past, and I feel uneasy with the equivocation of the government. Yet, as an artist Yoshiko Shimada argues, ‘the language used in the past by activists and feminists is not effective in moving younger audiences anymore. A dualistic rhetoric tends to paint everything as black and white, right and wrong, and divide individuals or groups into the oppressors or the victims. Instead, … we need to develop a new way of thinking about social and political issues which is aware of the complex nuances of difference through positioning by gender, race, class and sexuality’ (ibid.: 189-190). Moreover, the desire for one single history might be the desire to be released from the burden of the past by historicizing it. The awareness of silence seems to be crucial. When we become unaware of silence, silence could turns into the oblivion.

Language

Thinking about the inhumanity in the World War II, there is something that cannot be fully told within historical facts and even within language. Historical facts seem to be never enough. The writer ‘who attempts to say what cannot be said, to communicate what eludes language, to convey a unique experience in the history of mankind, … finds that language is inadequate to the task (Kane, 1984: 103). In City of Corpses, Ota writes that she does not want to use the word “hell” ‘because that would use up her vocabulary of horror, but there was no way to describe this scene other than as the wrath of hell’ (quoted in Tachibana, 1998: 49). Ota implies the limit of language. The word “hell” is not enough to express “the horror”. What silence contains are not only the unspoken but also the unspeakable. ‘The silence that the crime of Auschwitz imposes upon the historian, is a sign for the common person. Signs are not referents validatable under the cognitive regimen, they indicate that something which should be able to put into phrases cannot be phrased in the accepted idioms. … The silence that surrounds the phrase “Auschwitz was the extermination camp” is not a state of mind, … it is a sign that something remains to be phrased which is not, something which is not determined’ (Lyotard in Friedlander (ed.), 1992: 5). Here silence is not ‘identical with simple muteness, and the way language breaks down is itself a significant and even telling process’ (LaCapra in Friedlander (ed.), 1992: 111).

Theodor Adorno asserts the impossibility of the representation after Auschwitz, stating that ‘[he has] no wish to soften the saying that to write lyric poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’ (in Aroto and Gebhardt (eds.), 1998: 312). He means that it is impossible to represent the real suffering exactly the same within art. As Min-Ha argues, ‘[t]he truest representation of oneself always involves elements of fiction and of imagination, otherwise there is no representation, or else, only a dead, hence “false”, representation (1992: 168). Lyotard also argues that the unrepresentable exists. ‘[T]he historian must break with the monopoly over history granted to the cognitive regimen of phrases, and he or she must venture forth by lending his or her ear to what is not presentable under the rules of knowledge’ (1988: 57). However, Adorno further argues that ‘this suffering … demands the continued existence of art while it prohibits it; it is now virtually in art alone that suffering can still find its own voice, consolation, without immediately being betrayed by it’ (in Aroto and Gebhardt (eds.), op.cit.). Any atrocities have the dilemma that demand their representation, but at the same time, deny them. The atrocity is unimaginable because of its inhumanity, its monstrosity and its enormity (these words can never be enough).

Postomemorial Art

I would like to look at the notion of postmemory once again. As I mentioned above, postmemory is a powerful form of memory that is not produced out of recollection, but of projection of the others’ memories. Yet, at the same time, as Hirsch argues, postmemory also ‘implies distance between the self and the other’ (in Bal et al. (eds.), 1999: 9). In any genocidal acts that were taken place in the twentieth century, distance remains. ‘[T]he break between then and now, between the one who lived it and the one who did not, remains monumental and insurmountable, even as the heteropathic imagination struggles to overcome it (ibid.). Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger uses the term Matrix as a symbolic space where the self and the other coexist without fusion. According to her, ‘[i] n the Matrix a meeting occurs between the co-emerging I and the unknown non-I. Each one neither assimilates nor rejects the other and their energy consists neither in fusion nor in repulsion, but in continual re-adjustment of distances, within togetherness or proximity. Matrix is a zone of encounter between the most intimate and the most distanced unknown’ (1993: 12). Hirsch further suggests that ‘[t]he challenge of the postmemorial artist is precisely to find the balance that allows the spectator to enter the image, to imagine the disaster, but that disallows an overappropriative identification that makes the distances disappear, creating too available, too easy an access to this particular past’ (in Bal et al. (eds.), 1999: 10).

Bibliography

Adorno W. Theodor, “Commitment”, in Andrew Arato and Eike Gebhardt (eds.), The Essential Frankfurt School Reader, New York, 1998

Antze P. and M Lambek, “Introduction. Forecasting Memory” in Paul Antze and Michael Lambek (eds.), Tense Past. Cultural Essays in Trauma and Memory, London and New York, 1996

Derrida Jacques, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, Chicago, 1995

Ettinger L. Bracha, “Woman – Other – Thing: A matrixial touch”, in cat. Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger. Matrix – Borderlines, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, 1993

Foucault Michel, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, London, 1984

Friedlander Saul (ed.), Probing the Limits of Representation. Nazism and the “Final Solution”, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, 1992

Hariu Ichiro, Sengo Bijutsu Seisuishi (History of the rise and fall of post-war art in Japan), Tokyo, 1979

Hariu Ichiro, “Progressive Trends in Modern Japanese Art” in cat. Reconstructions: Avant-Garde Art in Japan 1945-1965,Museum of Modern Art Oxford, 1985

Hirsch Marianne, “Projected Memory: Holocaust Photographs in Personal and Public Fantasy”, in Mieke Bal et al. (eds.), Acts of Memory. Cultural Recall in the Present, Hanover and London, 1999

Kane Leslie, The Language of Silence: On the Unspoken and the Unspeakable in Modern Drama, London, 1984

Kikuhata Mokuma, Fujita yo Nemure: Ekaki to Senso (Fujita, Sleep in the grave: artists and war), Fukuoka, 1978

Lloyd Fran(ed.), Consuming Bodies: Sex and Contemporary Japanese Art, London, 2002

Min-Ha T. Trinh, Woman, Native, Other, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1989

Min-Ha T. Trinh, Framer Framed, London, 1992

Murakami Takashi, SUPER FLAT, Tokyo, 2000

Sobchack Vivian (ed.), THE PERSISTENCE OF HISTORY: cinema, television, and the modern event, New York and London, 1996

Tachibana Reiko, Narrative As Counter-Memory: A Half-Century of Postwar Writing in Germany and Japan, New York, 1998

Websites

Digital Art Resource for Education, http://www.dareonline.org

Revive Time Kaki Tree Project, http://www6.plala.or.jp/kaki-project/

Leave a reply to 螺旋工房クロニクル 泥鰌屋通信 Studio Spiral Chronicle Cancel reply