Memory and Silence in Japan Part2

How do Japanese artists respond to Japanese recent past?

Akiko Tanio(Funo)

Hiroshima・Nagasaki

Since there is no public history of the twentieth century, or it is still within silence and has not come up to the surface in Japan, art practices, which respond to the recent past, are various. It can be also said that the attitudes of the artists toward the past are different depending on their generations. Of course, there is a gap between the artists who experienced the War and those who were born after the War. The artists I would like to engage with also draws attention to various issues. Some artists usually do not deal with the War, on the other hand other practices of the artists are based on the War. Now I would like to look at works that deal with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. How each work responds to these two events is various. Some works imply the unrepresentability, and some works seem to focus on the act of remembrance and work as the counter-monuments.

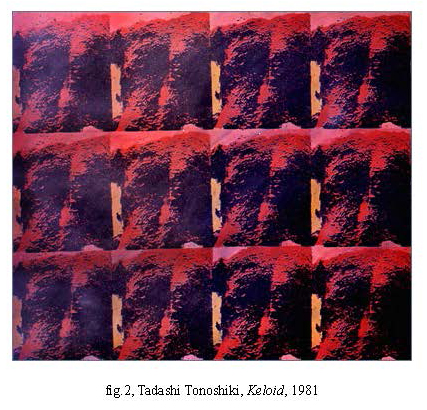

fig.2, Tadashi Tonoshiki, Keloid, 1981

Tadashi Tonoshiki was an artist who actually experienced the nuclear bomb in Hiroshima. He was three at that time. It was only in 1975 that he began to produce works dealing directly with the bombing based on his recollections of the explosion. He died of hepatic cancer caused by the nuclear radiation in 1992 at the age of fifty-three. Keloid (1981) (fig.2) is one of his works. It is a reddish, purplish grotesque painting. This work was originally part of a large installation in which this image covered the walls of an entire gallery. In this work, only the title refers to the nuclear bomb. The unspeakability resides in this work. Although he broke twenty years of silence, the unspeakablity remains. Probably the mushroom cloud is nothing to him. For him, some substance cannot represent it. The abstractness is his proximity to the explosion.

The chaos just after the explosion is also depicted in the A-Bomb literature and the diaries of people who experienced the nuclear bomb. For example, a doctor, Tatsuichiro Akizuki who experienced the nuclear bomb in Nagasaki recorded his experiences for a week after the bombing until the official defeat of Japan. He writes, on the 9th of August, ‘[w]e ran through collapsed houses and burnt-out fields with bare feet. The sky is dark and the ground is red. A stark-naked man, a blood-stained factory man, and a woman with dishevelled hair go this way and that. Everybody just wanted to escape somewhere, but nobody understood what had happened’ (quoted in Tachibana, 1998:35).

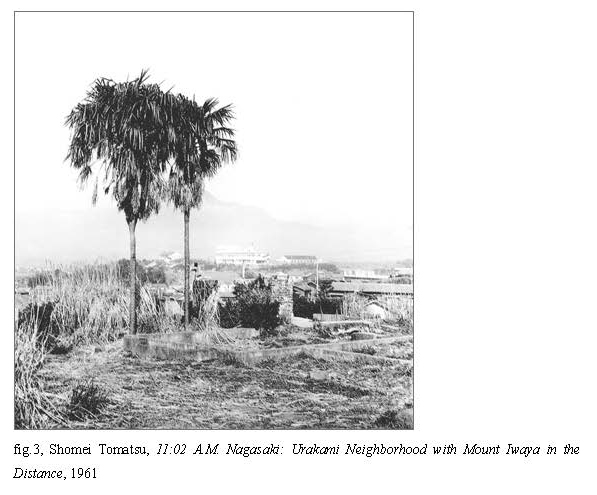

There are artists who keep taking photographs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Shomei Tomatsu is one of them. He was born in 1930 in a city quite close to the military base. Experiencing the occupation of the United States, he experienced the extraordinariness within the ordinariness. During the War, he was told by the adults how nasty the enemies, namely American soldiers, are. However, when he was suffering from the extreme hunger and the poverty, people who gave him food such as chocolate and chewing gum were American soldiers. The world shifted from one side to the other, and he could not believe anything. What he could believe was only what he could see. In 1950, he began to take photographs of ordinary people who were, at that time, American soldiers and half-American, half-Japanese children. In 1960, he was asked to take photographs in Nagasaki for antinuclear campaign. Next year, he started to take photographs of ordinary life in Nagasaki such as people, sites, things and so on and so forth. He was again faced with the extraordinariness within the ordinariness. He was confronted with the lack of aid, discrimination towards people who was the survivor of the nuclear bomb, and the poverty because they could not get a job. His photographs show the extraordinariness within the ordinariness. After World War II, Japan has pretended to have developed and built the country all over again in the shadow of the United States although it is impossible to start from a blank sheet. Even though the wounds are buried, they cannot be eliminated completely. The trace remains like Freud’s mystic writing-pad. As Tachibana argues, ‘in contrast to the claim that one era had been completed and a new one had begun was the fact that [Japan] saw the persistence of excessive materialism, ethnic and racial prejudice, authoritarian institutions, and other cultural trends of the sort that had contributed to the outbreak of World War Two and had been present throughout the war and afterward. In these respects, if a new age was being inaugurated it bore disturbing resemblances to the old – and perhaps no new age was beginning at all’ (1998: 249). Tomatsu’s photographs draw attention to counter-history. In 11:02 A.M. Nagasaki: Urakami Neighborhood with Mount Iwaya in the Distance (1961) (fig.3), a vulnerable tree stand in the field. Close to this site, there was Urakami Cathedral that was destroyed by the blast from the explosion. Tomatsu’s works also show the unrepresentability. All he can do is to take photographs of traces in which a sense of loss resides, and the effect of the nuclear bomb still remains.

fig.3, Shomei Tomatsu, 11:02 A.M. Nagasaki: Urakami Neighborhood with Mount Iwaya in the Distance, 1961

There is another artist who was haunted by the nuclear bomb dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Tatsuo Miyajima, born in 1957, first encountered with the nuclear bombing in Hiroshima when he was 17 years old on a school trip. He was confronted with the fact that he knew nothing about the nuclear bombings. Since then he could not forget the disquiet he felt in Hiroshima. As an artist, he usually produces works using LEDs with his three concepts: keep changing, connect with everything and continue forever. Since 1995, Miyajima started a project ‘Revive Time Kaki Tree Project’. It responds to a fading memory. Miyajima states, ‘even though the atomic bombings and the Holocaust infringed human rights occurred only a half century ago, memory of these crimes against humanity is beginning to fade. We should remember these crimes as important instructions. One reason for our failure to remember is that daily life today, particularly for the young, is so removed from the tragic events of the recent past. In effect, they have become isolated; become a “closed history”’ (from a Website, Revive Time Kaki Tree Project). Miyajima met the tree doctor, Dr. Ebinuma who had given birth to the second generation of kaki saplings from the trees that survived the nuclear bomb dropped in Nagasaki. Miyajima was deeply moved by alive, green saplings. Then this project started. Kaki saplings are distributed to hosts who applied for them over the world, and are raised by local people. The saplings transform and disseminate around the world with the memory of Nagasaki. Planting the sapling is not the end. It takes ten years to bloom flowers. It is also encouraged to have various activities along with growing kaki trees. The kaki saplings have the presence of the past in the present, and continue to exist over time and space.

The works of Masao Okabe (born in 1942) focus on activating the memory of the past. Since 1977, he has been doing frottage, which is the technique of placing a thin paper on an object and rubbing it with pencil or charcoal so that the form of the object appears. He made frottages of commemorative copperplate relieves representing scenes of the nuclear bomb ruins which were taken from a photograph, placed on streets on Hiroshima. He also made frottages of a plate on which is written ‘n’oubliez pas (don’t forget)’, in memory of the holocaust victims which sits on a gate in a Jewish ghetto in Paris. He welcomes residents or passers by to participate in the frottage and combines their cooperative efforts. In The Dark Face of The Light (1996-2002), he created the works from the remains of the old Ujina station in Hiroshima. Ujina station was built for the military usage when Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1894. The station is the site where Japanese colonial history began, and also the site where the nuclear bomb was dropped. Now the remains of the station are left in a vast empty space. Okabe created the frottages of the interstice between kerbstones of the plat form. He creates the trace of the trace using the method of frottage. The remains of the old Ujina station will soon disappear because the superhighway will be built. This work leaves the trace not to lose the memory of the war along with the loss of the remains. The act of frottage is in fact the act of memory and the act of commemoration. It also seems to me that he tries to uncover what is beneath the surface by peeling the surface off. Like Miyajima’s practice, Okabe’s practice brings the past in the present. They try to activate the past. Thus their works are the process rather than the finished. The act of planting, or the act of frottage seems to be more important than the outcome.

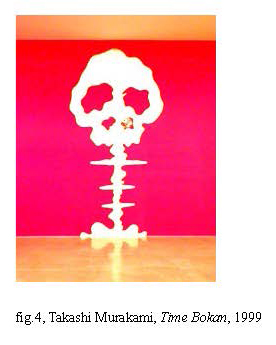

fig.4, Takashi Murakami, Time Bokan, 1999

Takashi Murakami (born in 1962) is probably the most famous Japanese contemporary artist in the West as well as in Japan. He focuses on otaku culture. Otaku is a term for people who are obsessed with comics, computer games and animation, and it has a negative meaning although the word itself means home. He also coined the term ‘super flat’ as an original concept of Japanese. In his super flat manifesto, he states that ‘[t]he world of the future might be like Japan is today – super flat. Society, customs, art, culture: all are extremely two-dimensional’ (2000: 5). Recently, he has exhibited a wall painting Time Bokan (1999) (fig.4). Bright red and orange on the background, the white skeleton and mushroom like figure appears at the centre. For western people, especially for the people of the United States, it would be immediately connected to the mushroom cloud of the nuclear bomb. However, it does not work like that for Japanese people. The mushroom cloud is a symbol of the nuclear bomb for the West. In this sense, this wall painting has got a distance both in time and space. It is a view of the nuclear bomb from the outside, and this spatial distance seems to imply the distance in time as well. The fact that a Japanese artist produced the representation of the nuclear bomb from the point of view of the outside seems to be significant. This work seems to freeze Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the past. Moreover, the title of this painting moves Japanese people’s attention away from the nuclear bomb. The title ‘Time Bokan’ is a name of a cartoon in which the skeleton like cloud with the explosion appears every time. However, how Murakami exhibits this work makes difference. In the exhibition Ground Zero Japan which was held in 1999-2000 at Art Tower Mito, Japan, Murakami exhibited an installation. With the wall painting Time Bokan, he put his earlier work, Sea Breeze (1992). Sea Breeze is made up with 16 lights that are used in a stadium. When the shutter opens, it gives off the blinding flash and the heat. With this work, Time Bokan suddenly becomes the symbol of the nuclear bomb, the mushroom cloud. This installation seems to emphasise that the mushroom cloud as the symbol of the nuclear bomb is only for other countries by adding the title ‘Time Bokan’ and Sea Breeze to the wall painting. This seems to question the representation of the nuclear bomb. Moreover, it also makes us people aware that we are always surrounded by the image of bombings.

Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

Each country has developed a different attitude towards its own past. Germany and Japan have dealt with World War II quite differently. As Elsaesser argues, Japan is a country that ‘appears until recently not even to have begun reflecting on the fact that the memory others have of it requires opening up its “history” to outside scrutiny. Germany, on the other hand, has often either invited such scrutiny or has not been allowed by others to forget events that cannot be contained in consensus accounts or exempted from contested representation” (in Sobchack (ed.), 1996: 146). The situation of Japan after the War has been complicated. There are still debates going on whether the War was the invasion or the self-defence among politicians before acknowledging the atrocities that Japanese military committed. There are also people who say that they cannot say anything about the nuclear bomb dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki without taking responsibility for other Asian countries. I do not agree with both of them. The atrocities such as Nanking Massacre and the nuclear bomb dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki both happened. In my opinion, the cause and the effect are not that important. It seems that the act of remembrance is very important in Japan before the past being distorted and forgotten, which it seems that it is already happening. There are some art practices that touch upon the hidden part of the official history and try to break the silence.

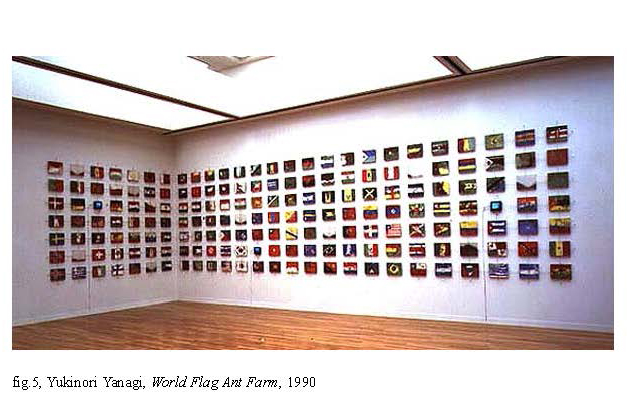

fig.5, Yukinori Yanagi, World Flag Ant Farm, 1990

Yukinori Yanagi, who was born in 1959, has been primarily working on the question of nation, borderline and system. In World Flag Ant Farm (1990) (fig.5), he created a series of interconnecting boxes, each filled with coloured sand in the pattern of a national flag that represents the nation of the world. He linked each flag to the other flag by plastic tubes. He then released ants into this system which were able to travel between all the networked flags, transporting food and sand. These border crossings eventually resulted in an intermingling of colour throughout the system.

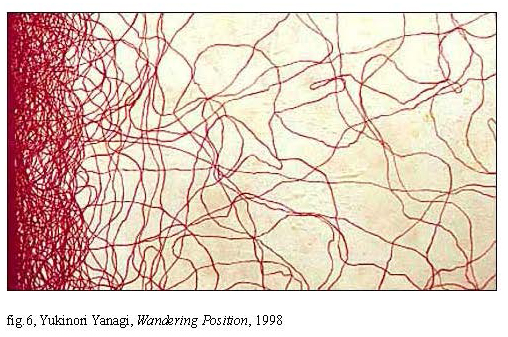

fig.6, Yukinori Yanagi, Wandering Position, 1998

In Wandering Position (1998) (fig. 6), Yanagi placed himself and an ant in a five metre square enclosure. For several hours each day the artist crawled around tracing the paths made by the ant with a red crayon. What interests me in these works is his awareness of the system or the limit represented by boxes and five metre square enclosure. Ants were allowed to wander only within the enclosure. After all, it has been programmed for ants to perform. As Yanagi states, ‘we feel that the incarcerated lack liberty, and that all of their activity is controlled and watched and we assume that this is completely opposite to the way we live our daily life, but I ask myself … Is what I watch, what I watch by my will? Is the direction I am walking determined by me? Is what I am thinking really thought by me? What drives journeys through life?’ (from a Website, Digital Art Resource for Education).

fig.7, Yukinori Yanagi, PacificK100B (an installation), 1997

Around the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II, Yanagi started to draw attention to World War II, especially Pacific War. In 1997, he produced an installation Pacific K100B (fig.7). In this work, he reproduced a Japanese warship sunken during World War II. Furthermore, he drew attention to a rather unknown history even for Japanese people. From 1998, he started a project that involves two warships, Akitsushima and Irako, both now sitting at the bottom of the Philippine Sea. He went to the Philippine Sea with video and still cameras, and he documented several of his dives seeking for the warships. The dives are diagrammed in a series of small computer printouts, with red, hand-drawn lines illustrating the artist’s paths over the sunken warships. As the war ships are submerged under the beautiful sight of the Philippine Sea, the memory of war is hidden away. Yanagi’s act is a journey to seek for what is silenced. It seems to me that he is acting his desire metaphorically. It also seems that his project is his resistance to forget the past although what he gets from the sea are rusted fragments that are hard to recognize what exactly they are.

In Yanagi’s another work, a giant heavy carpet lies in a room. It is a shape of Japanese passport, but there is not a chrysanthemum at the centre. Only one petal is left. Other petals are scattered about. Just as in the case of a lover plucking off the petals of a flower each by each to examine whether his or her feelings are reciprocated, each petal has been given the tile of ‘loves me’ and ‘loves me not’ with languages of 13 different countries and areas; Korea, Myanmar, Laos, China, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Brunei, Okinawa and Ainu in Northern Japan. All of these countries were once comprised in the Greater East Asian Coprosperity Sphere that Japan had imposed upon the region during World War II. The chrysanthemum is Japanese imperial symbol. Usually national symbols are used on passports, but Japan does not have such a symbol. That is why the imperial symbol is used on Japanese passport. On the other side of the carpet, the 19th, 20th and 21st Articles of the Japanese Constitution are inscribed. They are related to the freedom of thought, religious, belief, speech and expression. They cannot be seen, and it would be too heavy to turn the carpet over. On the wall, there are war paintings that were produced by Kiyoo Kawamura, Kanetaro Tojo, Icihiro Fukuzawa and Saburo Miyamoto. Like his Pacific K100B, it works as a memory trigger. Japan invaded and conquered countries on the carpet during in the name of liberation. Passport has a peculiar characteristic. It is both liberation and restriction. You can go to other countries with a passport, but simultaneously it can be said that you have to have a passport, the nationality to go to other countries. It also reminds Japanese people that the passport, which represents your identity, always wears the imperial symbol. The 19th, 20th and 21st Articles of the Japanese Constitution also have the contradiction. They are restriction that promises you the freedom. Yanagi problematises the fact that war paintings were hidden away, and shows the contradiction of the Articles of the Japanese Constitution by juxtaposing them.

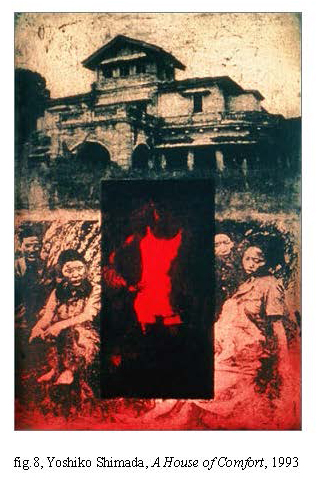

fig.8, Yoshiko Shimada, A House of Comfort, 1993

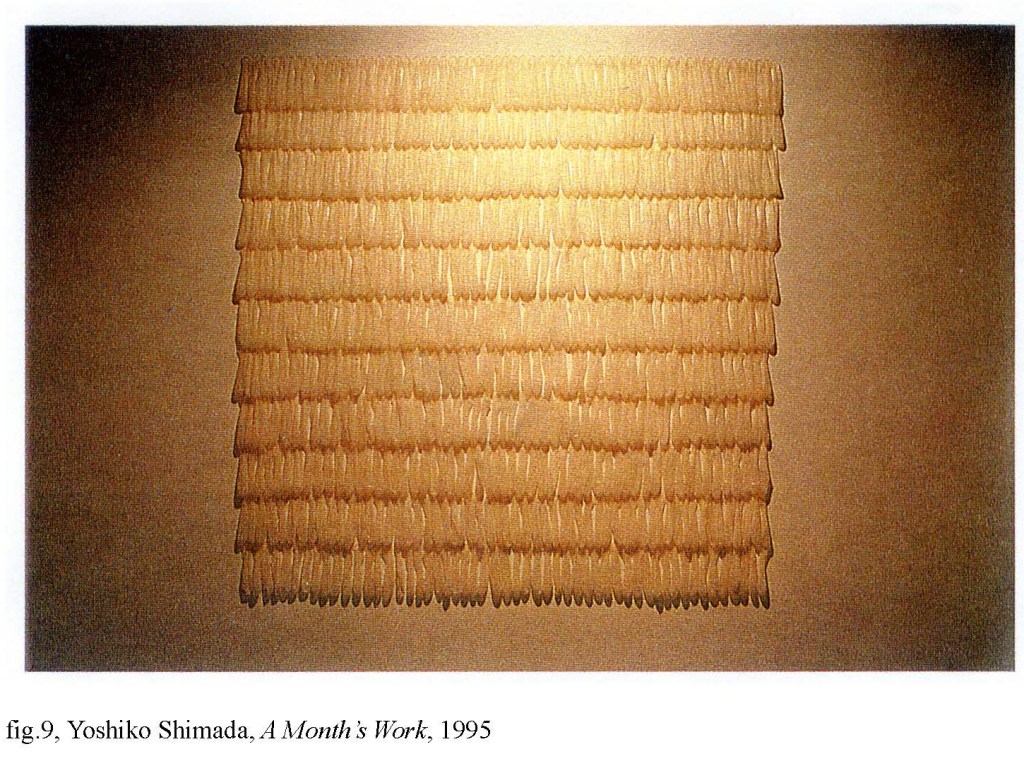

fig.9, Yoshiko Shimada, A Month’s Work, 1995

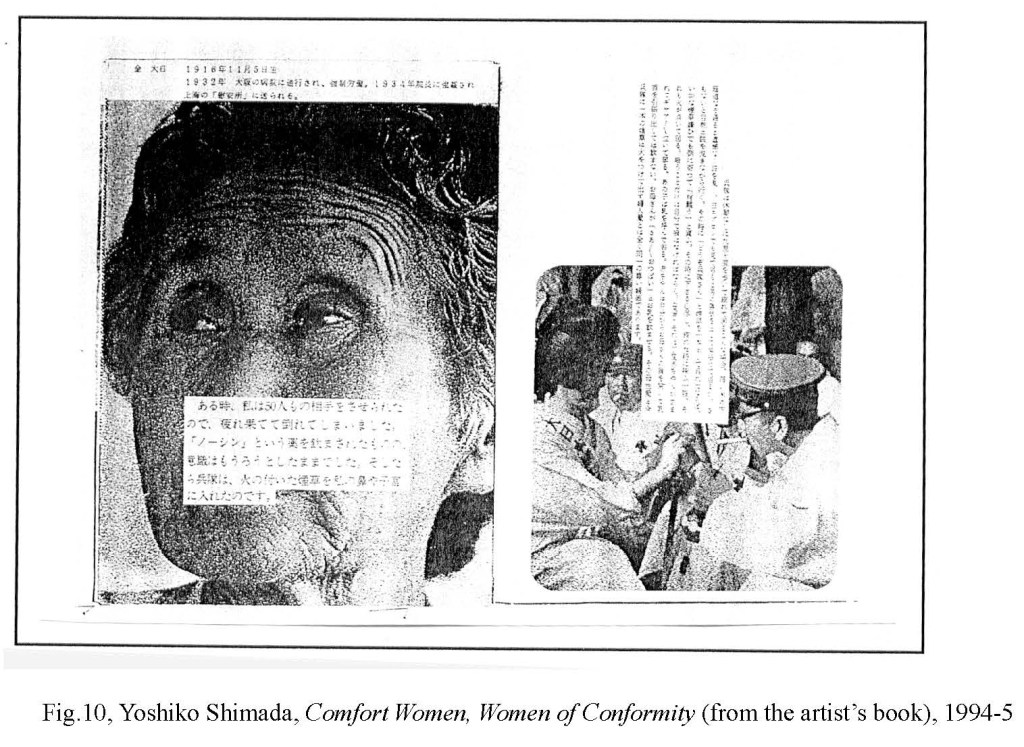

Fig.10, Yoshiko Shimada, Comfort Women, Women of Conformity (from the artist’s book), 1994-5

Military Comfort Woman

Yoshiko Shimada (born in 1959) is also the artist of post-war generation. Her main focus is the issues of gender, power and nation, and her works centres on issues of sex and consumerism in contemporary Japan in which she makes a connections between ‘the war years, characterized by the rise of nationalism and imperialism, the immediate post-war period, when Japan was occupied by American forces, and, more recently, Japan’s current cultural position within Asia’ (Lloyd in Loyd(ed.), 2002: 84). She locates her works in the political, historical and social context, and questions the way Japanese people have neglected its own past. Her works uncovers repressed histories, and she has produced works which deal with comfort women since 1993. Her works are rather explicit. InA House of Comfort (1993) (fig.8), the military brothel and Asian prostitutes are juxtaposed with a Korean comfort woman standing at the centre. A Month’s Work (1995) (fig.9) is ‘made up of 600 pink condoms in serried rows. [I]t refers to the Korean comfort women’s accounts of the number of men they were forced to serve in a system of enslaved labour, even though many suffered from the painful effects of venereal disease’ (ibid.: 87). She often juxtaposes a woman as object of sex and a woman as a sacred mother. In a handmade artist’s book Comfort Women, Women of Conformity (1994-5) (fig.10), she juxtaposed a Korean woman’s face on the left page with a Japanese woman lighting a soldier’s cigarette on the right page. A statement is attached to each figure. A Korean woman states, ‘once, I had to serve fifty men, and I was so tired. I was given a medicine, but I was still feeling dim. Then the soldier put the cigarette lit into my nose and the womb’ (my translation). On the right page, a Japanese soldier states that how he appreciates the kindness of women. When he is tired, they give him cigarette and light it. He also mentions about white apron, which women wear, that give him energy. In her works, Shimada explicitly asserts the necessity of rethinking Japanese recent past by deploying repressed histories of comfort women. At the same time, she also argues that the issue of comfort women is not the things in the past. A Month’s Work also implies that many non-Japanese women are employed in sex industry. Her works explore ‘how attitudes to women sexuality and the commodification of sex in contemporary Japan are related to deep-rooted issues of nation, race and gender’ (Lloyd in Lloyd (ed.), 2002: 89).

War painting returns

Yanagi and Shimada both touch upon Japanese unpleasant, hidden or repressed histories. Shimada uncovers the repressed histories within her works, whereas Yanagi focuses on the obscurity of the silence in contemporary Japan. He dives into the sea to find something tangible, and something he can grasp, but he ends up finding rusted weapons or fragments of iron. The fragments do not tell many things about the past. Thus he again dives into the sea. It is a repetition of trying to find something tangible which will never be tangible. The fact tells little. The fact is never enough.

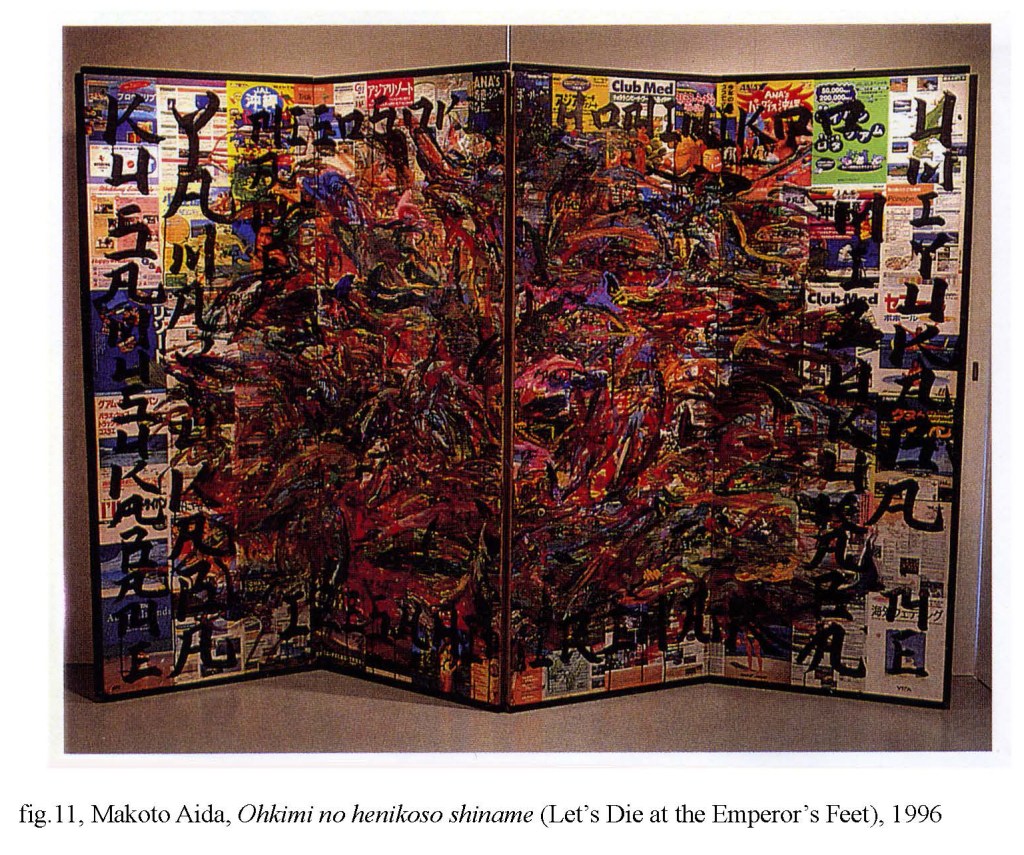

fig.11, Makoto Aida, Ohkimi no henikoso shiname (Let’s Die at the Emperor’s Feet), 1996

Like Shimada, a young artist Makoto Aida (born in 1965) draws attention to the relationship between the present and the past. Aida produced a series called Sensoga Returns (War painting returns) from 1995 to 1996. The series includes Utsukushii hata (Beautiful Flag) (1995) in which a Japanese and a Korean girl in their school uniforms and holding their national flags are facing each other, Picture of an Air Raid on New York (1996) in which New York city is on fire and battle planes are flying above drawing a sign of infinity, No One Knows the Title (1996) in which the image of the Parthenon is imposed on the image of the Atomic Bomb Memorial Dome in Hiroshima and Ohkimi no henikoso shiname (Let’s Die at the Emperor’s Feet) (1996) (fig.11). All paintings are produced on folding screens. I would like to focus on Ohkimi no henikoso shiname. What is in this work is the jumble. On the background, travel-agency advertisements are pasted. They are ads of the southern islands which are transformed from the site of massacre into tropical resorts attracting Japanese tourists today. According to Aida, dead dolphins are depicted on the ads. The dolphins refer to the incident of their mass suicide. Several hundreds of dolphins were found dead on the beach of Nagasaki, and the local fishermen eating them were severely criticised by international ecologists. The word ‘JAP’ is written on each dolphin except for one. On one dolphin, the name ‘Harumi’ is written, who was an adopted child of a literary critic Shinobu Origuchi, and died in one of the southern islands during the War. The lyrics of a military song, which was used as a BGM on the radio during the War, is also written with deformed alphabets.

Aida’s series Sensoga Returns could be dangerous. The series can be seen as a cry for nationalism. Yet, what Aida exposes is not nationalism at all. What he exposes is the jumble, the chaos and the fragility of contemporary Japan. It is the chaos that resides within the silence, and that is buried. As Midori Matsui argues, ‘Sensoga Returns was not made with the purpose of inciting nationalism. Aida’s purpose was to use the negative outcome of Japanese modernisation as an occasion for criticizing the hypocrisy of post-war democracy, and the tanting effects of its uncritical continuation of “incomplete modernity” on the present Japanese consciousness’ (in Lloyd (ed.), 2002: 154). Aida states that he ‘acknowledge[s] the inevitability of war, discrimination and bullying because they are caused by [the] erotic drive. Without recognizing this, there’s no coming up with an effective way to prevent them. [He thinks] that the hysterical idealism enforcing the slogan of “love and peace” merely confuses the situation’ (quoted in ibid.: 164). The jumble on the travel-agency ads seems to be Aida’s attempt to break the silence. Or rather, it might be his abject for the disguised pacifism that can only exist by silencing the past. In this work, the jumble, which is buried under the ads, appears on the surface.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Japan was defeated in the Second World War, and many cities fell into ruins. Everything disappeared. On the empty field, Japan has rebuilt buildings and the country. As a result, Japan has become a peace and economically rich country. However, Japan as peace and economically rich came into existence only by silencing the past. The authority has utilized silence, and has repressed history. Therefore, the act of postmemory has been limited in Japan. It cannot be denied that the utilization of silence by the authority and the lack of postmemory led to Japanese people’s ignorance of history. The history of the twentieth century is silenced in teaching history, and the responsibility of the emperor Hirohito and war paintings were silenced. Yet, ‘silencing’ is only one aspect of the silence. Silence contains the unsaid, and it also contains the unspeakability and the unrepresentability. I am not saying that remaining silence is good. Rather, I think that silence has the power to make people imagine what is buried, what is veiled and what is hidden. As long as there is silence, there can be the act of breaking the silence. The works and practices of the Japanese artists, which I discussed, seem to approach to the silence in various ways. The work of Tadashi Tonoshiki implies the unrepresentability by breaking his own silence. The works of Shomei Tomatsu draws attention to survivors of the Atomic Bomb and indicates that History is also surrounded by the silence. Memory is ambiguous, but the official history, History with capital H is also ambiguous. Yukinori Yanagi took a journey to the Philippines Sea to search for something hidden in the silence. Yoshiko Shimada breaks silence by uncovering the past. The art practice of Tatsuo Miyajima brings the past into the present, and problematizes the oblivion of the past in Japanese society. Masao Okabe creates the trace of the ruins not to lose the memory of the War. Takashi Murakami seems to question the mushroom cloud as the symbol of the Atomic Bomb by painting the mushroom cloud deliberately. Makoto Aida draws attention to the similarity between the past and the present. In his work, the jumble that resides within the silence appears on the surface in the present. In that way, he criticises Japan that cries for peace without facing the past. Silence has the possibility of holding the past in the present instead of freezing the past as the past. Thus we should always be aware of the silence. When we become unaware of the silence, it is the real threat of forgetting the World War II.(18/9/2003)

Bibliography

Adorno W. Theodor, “Commitment”, in Andrew Arato and Eike Gebhardt (eds.), The Essential Frankfurt School Reader, New York, 1998

Antze P. and M Lambek, “Introduction. Forecasting Memory” in Paul Antze and Michael Lambek (eds.), Tense Past. Cultural Essays in Trauma and Memory, London and New York, 1996

Derrida Jacques, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, Chicago, 1995

Ettinger L. Bracha, “Woman – Other – Thing: A matrixial touch”, in cat. Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger. Matrix – Borderlines, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, 1993

Foucault Michel, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, London, 1984

Friedlander Saul (ed.), Probing the Limits of Representation. Nazism and the “Final Solution”, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, 1992

Hariu Ichiro, Sengo Bijutsu Seisuishi (History of the rise and fall of post-war art in Japan), Tokyo, 1979

Hariu Ichiro, “Progressive Trends in Modern Japanese Art” in cat. Reconstructions: Avant-Garde Art in Japan 1945-1965,Museum of Modern Art Oxford, 1985

Hirsch Marianne, “Projected Memory: Holocaust Photographs in Personal and Public Fantasy”, in Mieke Bal et al. (eds.), Acts of Memory. Cultural Recall in the Present, Hanover and London, 1999

Kane Leslie, The Language of Silence: On the Unspoken and the Unspeakable in Modern Drama, London, 1984

Kikuhata Mokuma, Fujita yo Nemure: Ekaki to Senso (Fujita, Sleep in the grave: artists and war), Fukuoka, 1978

Lloyd Fran(ed.), Consuming Bodies: Sex and Contemporary Japanese Art, London, 2002

Min-Ha T. Trinh, Woman, Native, Other, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1989

Min-Ha T. Trinh, Framer Framed, London, 1992

Murakami Takashi, SUPER FLAT, Tokyo, 2000

Sobchack Vivian (ed.), THE PERSISTENCE OF HISTORY: cinema, television, and the modern event, New York and London, 1996

Tachibana Reiko, Narrative As Counter-Memory: A Half-Century of Postwar Writing in Germany and Japan, New York, 1998

Websites

Digital Art Resource for Education, http://www.dareonline.org

Revive Time Kaki Tree Project, http://www6.plala.or.jp/kaki-project/

Afterword by Shuji Funo

Since “Memory and Silence” (2003), books on “war paintings” and other topics related to “war and art” have been published in Japan, including Noyori Sawaragi’s (2005) “War and Expo” (Bijutsu Shuppansha) and Noyori Sawaragi’s (2006) “What Happened to Art?” 1992-2006, Kokusho Kankokai, edited by Hariu Ichiro (2007); War and Art 1937-1945, Kokusho Kankokai, Shukichi Hirayama (2015); War Paintings Returns: Tsuguharu Foujita and the Flowers of Attu Island, Geijutsu Shinbunsha, Robert Eagleston (2013); The Holocaust and Postmodernism: How Did History, Literature, and Philosophy Respond?, translated by Tajiri Yoshiki and Ota Susumu, Misuzu Shobo, supervised by Hayashi Yoko (2014); Collection of Tsuguharu Foujita Artworks, three volumes, Shogakukan, Akihisa Kawata (2014); Artists and War, Taiyo Japanese Heart Special Edition 220, Heibonsha, Noyori Sawaragi and Makoto Aida (2015); War Paintings and Japan, Kodansha, Takataka Iida (2016); War and Art His works include “The Terror and Illusion of Beauty” (Rittosha), “Tsuguharu Foujita: Writings During Wartime: Collection of Newspaper and Magazine Contributions 1935-1956” (Minerva Shobo), edited by Tsuguharu Foujita and Yoko Hayashi (2018), and “Artists’ War Responsibility: Thinking Through Tsuguharu Foujita’s ‘Suicide Attack on Attu Island’ (The War Not Written in Textbooks)” (Nashinokisha), among others.

Tanio Akiko has left behind materials such as drafts (Figure 1), lecture notes, references, citations and copies of them, but the one that appears to have had a major influence on her in putting together her thesis was the graduate school lecture “Memory and Cultural History” (2002-03) given by Astrid Schmetterling, lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London (Figure 2). The collection of lecture materials for this lecture consists of 13 essays by W. Benjamin, S. Freud, J. Derrida, T.W. Adorno, and others, including Marianne Hirsch’s essay “Projected Memory,” included in The Act of Remembering, edited by Mieke Ball et al. Astrid Schmetterling has also written books such as Visual Culture as Recollection. For the core art history course, students are required to read E.H. Gombrich’s “History of Art” beforehand, and the syllabus lists references for each lecture topic, such as “From Art History to Histories of Art and Visual Culture,” “Revisiting Tradition,” “From Tradition to Formalist Modernism,” “Social History of Art,” “Postmodern Criticism of Modernity and Modernism,” “Author and Authority,” “Feminist Interventions in History (Art History),” “Gaze,” “Identity and Difference,” “Museology and Collecting,” and “Cultural Memory,” as well as providing a large number of printed materials.

She appears to have independently collected historical documents regarding Japanese artists, but he also attended a symposium entitled “Contemporary Japanese Popular Culture” co-hosted by Kingston University and SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies), University of London, on March 28, 2003, which included participants such as Mori Yoshitaka (“Interconnections: Contemporary Japanese Art, Literature, and Popular Culture in the 1980s and 1990s”), Takahashi Mizuki (“Gestures and Attitudes: The Relationship between Manga and Japanese Popular Culture”), Nakamura Ichiya (“Japan and Popular Culture”), and Sawaragi Noyori (“Neo-Pop, Otaku, and Aum Shinrikyo: World War II and Japanese Subcultures”). Marianne Hirsch, who first proposed the concept of “postmemory” in her essay “The Family Photograph” (1992), which discussed the relationship between the memories of children of Holocaust survivors and their parents, has since deepened her considerations in works such as The Family Frame (1997), Ghosts in the House (2010), and The Making of Postmemory (2012), and the discussion is expanding further.

Leave a reply to Memory and Silence in Japan Part2 – 螺旋工房クロニクル 泥鰌屋通信 Studio Spiral Chronicle Cancel reply